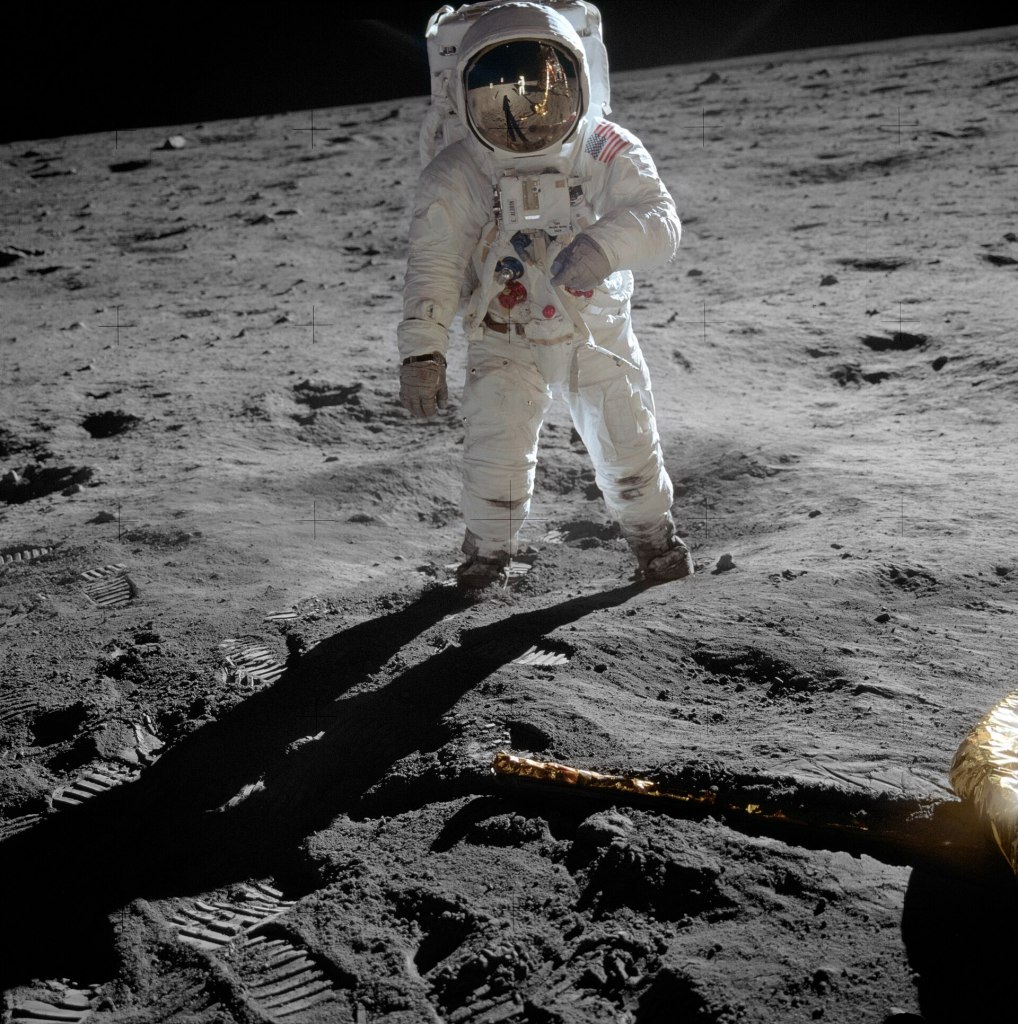

You have no doubt heard of Neil Armstrong, first human on the moon. But have you heard of Margaret Hamilton? She was the lead engineer, responsible for the Apollo mission software that got him there, and ultimately for ensuring the lunar module didn’t crash land due to a last minute emergency.

Being a great software engineer means you have to think of everything. You are writing software that will run in the future encountering all the messiness of the real world (or real solar system in the case of a moon landing). If you haven’t written the code to be able to deal with everything then one day the thing you didn’t think about will bite back. That is why so much software is buggy or causes problems in real use. Margaret Hamilton was an expert not just in programming and software engineering generally, but also in building practically dependable systems with humans in the loop. A key interaction design principle is that of error detection and recovery – does your software help the human operators realise when a mistake has been made and quickly deal with it? This, it turned out, mattered a lot in safely landing Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin on the moon.

As the Lunar module was in its final descent dropping from orbit to the moon with only minutes to landing, multiple alarms were triggered. An emergency was in progress at the worst possible time. What it boiled down to was that the system could only handle seven programs running at once but Buzz Aldrin had just set an eighth running. Suddenly, the guidance system started replacing the normal screens by priority alarm displays, in effect shouting “EMERGENCY! EMERGENCY”! These were coded into the system, but were supposed never to be shown, as the situations triggering them were supposed to never happen. The astronauts suddenly had to deal with situations that they should not have had to deal with and they were minutes away from crashing into the surface of the moon.

Margaret Hamilton was in charge of the team writing the Apollo in-flight software, and the person responsible for the emergency displays. She was covering all bases, even those that were supposedly not going to happen, by adding them. She did more than that though. Long before the moon landing happened she had thought through the consequences of if these “never events” did ever happen. Her team had therefore also included code in the Apollo software to prioritise what the computer was doing. In the situation that happened, it worked out what was actually needed to land the lunar module and prioritised that, shutting down the other software that was no longer vital. That meant that despite the problems, as long as the astronauts did the right things and carried on with the landing, everything would ultimately be fine.

There was still a potential problem though, When an emergency like this happened, the displays appeared immediately so that the astronauts could understand the problem as soon as possible. However, behind the scenes the software itself that was also dealing with them, by switching between programs, shutting down the ones not needed. Such switchovers took time In the 1960s Apollo computers as computers were much slower than today. It was only a matter of seconds but the highly trained human astronauts could easily process the warning information and start to deal with it faster than that. The problem was that, if they pressed buttons, doing their part of the job continuing with the landing, before the switchover completed they would be sending commands to the original code, not the code that was still starting up to deal with the warning. That could be disastrous and is the kind of problem that can easily evade testing and only be discovered when code is running live, if the programmers do not deeply understand how their code works and spend time worrying about it.

Margaret Hamilton had thought all this through though. She had understood what could happen, and not only written the code, but also come up with a simple human instruction to deal with the human pilot and software being out of synch. Because she thought about it in advance, the astronauts knew about the issue and solution and so followed her instructions. What it boiled down to was “If a priority display appears, count to 5 before you do anything about it.” That was all it took for the computer to get back in synch and so for Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong to recover the situation, land safely on the moon and make history.

Without Margaret Hamilton’s code and deep understanding of it, we would most likely now be commemorating the 20th July as the day the first humans died on the moon, rather than being the day humans first walked on the moon.

– Paul Curzon, Queen Mary University of London

More on …

Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish a new post to the CS4FN blog.

This blog is funded by EPSRC on research agreement EP/W033615/1.