By Jo Brodie and Paul Curzon, Queen Mary University of London

Some people have a neurological condition called face blindness (also known as ‘prosopagnosia’) which means that they are unable to recognise people, even those they know well – this can include their own face in the mirror! They only know who someone is once they start to speak but until then they can’t be sure who it is. They can certainly detect faces though, but they might struggle to classify them in terms of gender or ethnicity. In general though, most people actually have an exceptionally good ability to detect and recognise faces, so good in fact that we even detect faces when they’re not actually there – this is called pareidolia – perhaps you see a surprised face in this picture of USB sockets below.

How about computers? There is a lot of hype about face recognition technology as a simple solution to help police forces prevent crime, spot terrorists and catch criminals. What could be bad about being able to pick out wanted people automatically from CCTV images, so quickly catch them?

What if facial recognition technology isn’t as good at recognising faces as it has sometimes been claimed to be, though? If the technology is being used in the criminal justice system, and gets the identification wrong, this can cause serious problems for people (see Robert Williams’ story in “Facing up to the problems of recognising faces“).

“An audit of commercial facial-analysis tools

The unseen Black faces of AI algorithms

found that dark-skinned faces are misclassified

at a much higher rate than are faces from any

other group. Four years on, the study is shaping

research, regulation and commercial practices.”

(19 October 2022) Nature

In 2018 Joy Buolamwini and Timnit Gebru shared the results of research they’d done, testing three different commercial facial recognition systems. They found that these systems were much more likely to wrongly classify darker-skinned female faces compared to lighter- or darker-skinned male faces. In other words, the systems were not reliable. (Read more about their research in “The gender shades audit“).

“The findings raise questions about

Study finds gender and skin-type bias

how today’s neural networks, which …

(look for) patterns in huge data sets,

are trained and evaluated.”

in commercial artificial-intelligence systems

(11 February 2018) MIT News

Their work has shown that face recognition systems do have biases and so are not currently at all fit for purpose. There is some good news though. The three companies whose products they studied made changes to improve their facial recognition systems and several US cities have already banned the use of this tech in criminal investigations. More cities are calling for it too and in Europe, the EU are moving closer to banning the use of live face recognition technology in public places. Others, however, are still rolling it out. It is important not just to believe the hype about new technology and make sure we do understand their limitations and risks.

More on

Further reading

- Study finds gender and skin-type bias in commercial artificial-intelligence systems (11 February 2018) MIT News [EXTERNAL]

- Facial recognition software is biased towards white men, researcher finds (11 February 2018) The Verge [EXTERNAL]

- Go read this special Nature issue on racism in science (21 October 2022) The Verge [EXTERNAL]

- EU moves closer to passing one of world’s first laws governing AI (14 June 2023) The Guardian [EXTERNAL]

More technical articles

• Joy Buolamwini and Timnit Gebru (2018) Gender Shades: Intersectional Accuracy Disparities in Commercial Gender Classification, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research 81:1-15. [EXTERNAL]

• The unseen Black faces of AI algorithms (19 October 2022) Nature News & Views [EXTERNAL]

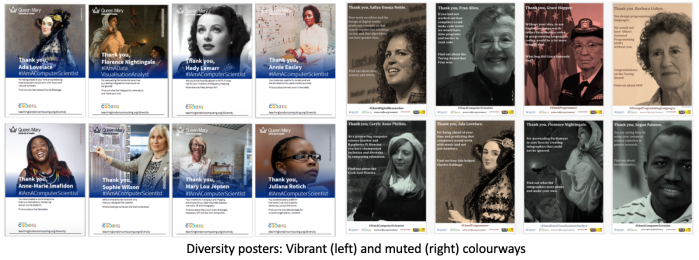

See more in ‘Celebrating Diversity in Computing‘

We have free posters to download and some information about the different people who’ve helped make modern computing what it is today.

Or click here: Celebrating diversity in computing

EPSRC supports this blog through research grant EP/W033615/1.

One thought on “Recognising (and addressing) bias in facial recognition tech #BlackHistoryMonth”