Algorithms for writing together

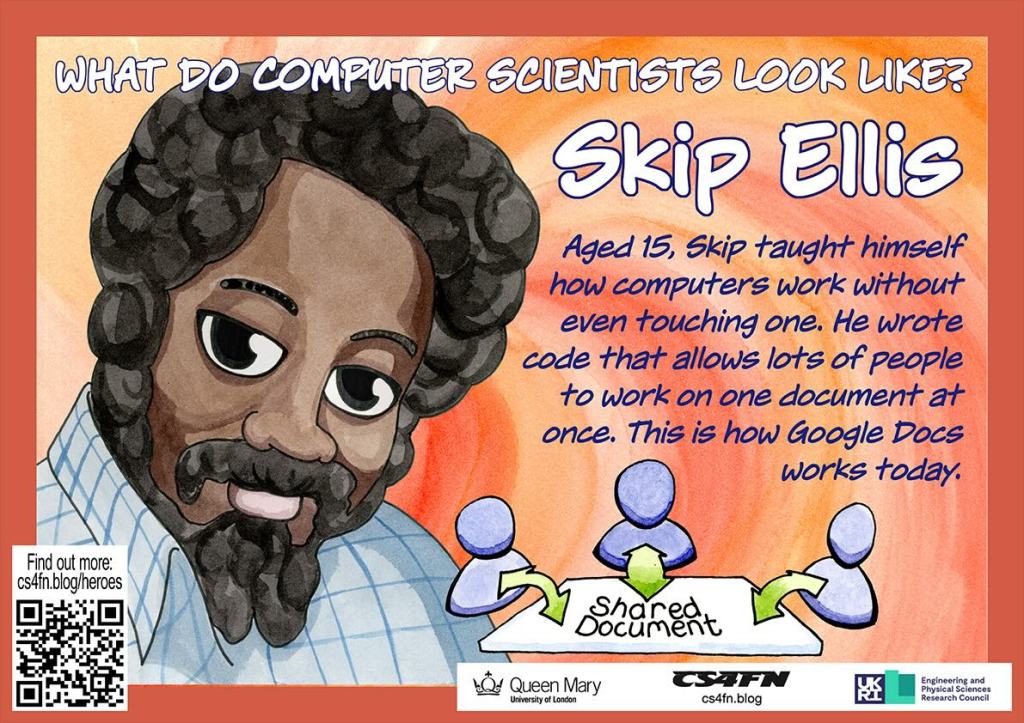

How do online word processing programs manage to allow two or more people to change the same document at the same time without getting in a complete muddle? One of the really key ideas that makes collaborative writing possible was developed by computer scientists, Clarence Ellis and Simon Gibbs. They called their idea ‘Operational transformation’.

Let’s look at a simple example to illustrate the problem. Suppose Alice and Bob share a document that starts:

"MEETING AT 10AM"

First of all one computer, called the ‘server’, holds the actual ‘master’ document. If the network goes down or computers crash then its that ‘master’ copy that is the real version everyone sees as the definitive version.

Both Alice and Bob’s computers can connect to that server and get copies to view on their own machines. They can both read the document without problem – they both see the same thing. But what happens if they both start to change it at once? That’s when things can get mixed up.

Let’s suppose Alice notices that the time in the document should be PM not AM. She puts her cursor at position 14 and replaces the letter there with P. As far as the copy she is looking at is concerned, that is where the faulty A is. Her computer sends a command to the server to change the master version accordingly, saying

CHANGE the character at POSITION 14 to P.

The new version at some point later will be sent to everyone viewing. However, suppose that at the same time as Alice was making her change, Bob notices that the meeting is at 1 not 10. He moves his cursor to position 13, so over the 0 in the version he is looking at, and deletes it. A command is sent to the server computer:

DELETE the character at POSITION 13.

Now if the server receives the instructions in that order then all is ok. The document ends up as both Bob and Alice intended. When they are sent the updated version it will have done both their changes correctly:

"MEETING AT 1PM"

However, as both Bob and Alice are editing at the same time, their commands could arrive at the server in either order. If the delete command arrives first then the document ends up in a muddle as first the 13th position is deleted giving.

"MEETING AT 1AM"

Then, when Alice’s command is processed the 14th character is changed to a P as it asks. Unfortunately, the 14th character is now the M because the deleted character has gone. We end up with

"MEETING AT 1AP"

Somehow the program has to avoid this happening. That is where the operational transformation algorithm comes in. It changes each instruction, as needed, to take other delete or insert instructions into account. Before the server follows them they are changed to ones so that they give the right result whatever order they came in.

So in the above example if the delete is done first, then any other instructions that arrive that apply to the same initial version of the document are changed to take account of the way the positions have changed due to the already applied deletion. We would get and so apply the new instructions:

STARTING FROM "MEETING AT 10AM"

DELETE the character at POSITION 13.

CHANGE the character at POSITION (14-1) to P.

Without Operational Transformation two people trying to write a document together would just be frustrating chaos. Online editing would have to be done the old way of taking it in turns, or one person making suggestions for the other to carry out. With the algorithm, thanks to Clarence Ellis and Simon Gibbs, people who are anywhere in the world can work on one document together. Group writing has changed forever.

Paul Curzon, Queen Mary University of London

This article was originally published on the CS4FN website.

More on …

EPSRC supports this blog through research grant EP/W033615/1.

The original version of this article was funded by the Institute of Coding.