Victorian, William Stanley Jevons was born in Liverpool in 1835. He was famous in his day as an economist and his smash hit book ‘The Coal Question’ drew the nation’s attention to the reduction in Britain’s coal supplies. He was the first economist to raise the issue of the ecological impact of economics. Jevons had other strings to his bow though and one of the strangest for the time if also incredibly forward thinking was his 1869 “logic piano”: a device that looked a little like a piano but that “played” logic.

Jevons was fascinated with logic and reasoning. He believed you could start with one thing (a premise) and from this work through a chain of reasoning to the conclusion. He thought that this could be done for everything. This was based on a principle he espoused of “the substitution of similars”: essentially reasoning based on the idea that “Whatever is true of a thing is true of its like”, For example, If Pharaohs are gods and Rameses is a Pharaoh (so is one of the things “like” a Pharaoh) then you can conclude Rameses is a god. He built on, and combined the ideas of, the Ancient Greeks with the then new ideas of George Boole, that we now call Boolean logic.

Boolean logic is based on a system of algebra using only the values of true and false (or 1 and 0), with operations corresponding to logical operations such as AND and OR that turn true/false values into new true/false values. This is the logic upon which computers are founded. A key idea was that you can abstract away from actual statements about truth in the real world and just replace them with variables that can stand for anything. Boole had laboriously shown using his logic how new abstract facts could be deduced from existing ones. Jevons realised that when reasoning was thought of like this, it became a mechanical process…and that meant a machine could do it.

His contemporary, Charles Babbage had been working on the idea of building mechanical “computers” but Babbage’s fundamental idea was that machines could do calculation. Jevon’s idea was slightly different and more fundamental: that machines could do logical reasoning, deducing new facts from existing ones. This was an idea that eventually came to fruition in the 20th century with the development of theorem provers where computers were programmed to do complex logical reasoning, even working on building up the whole of mathematics by proving ever more theorems from a few starting facts.

So, (with the help of an unknown craftsperson), Jevons set about designing and building his wooden Logic Piano. The idea was that you could put in the premises, the basic facts, by playing the keys of the “piano”. It would then mechanically apply his reasoning rules to discover all conclusions that could be deduced, altering its conclusion with each new fact added, The keys moved rods and levers that made logical facts appear on (or disappear from) the “display” of the machine – essentially facts on the rods appeared in slots cut into the back of the piano.

The kind of logical problem his machine worked with are Syllogisms (see Superhero Syllogisms). They were invented by the Ancient Greeks who were very good at logic. A syllogism is just a common pattern that combines facts where you figure out a conclusion only using the facts supplied, slotted into a template. For example, if we know facts 1 and 2 in the following template (where you can swap in anything for A, B and C) then we can create a new fact as shown.

So let’s replace A with the word superheroes, B with fight crime and C with my favourite superhero, Ghost Girl. If we put them in to the template above we get a new “fact” deduced from two existing ones:

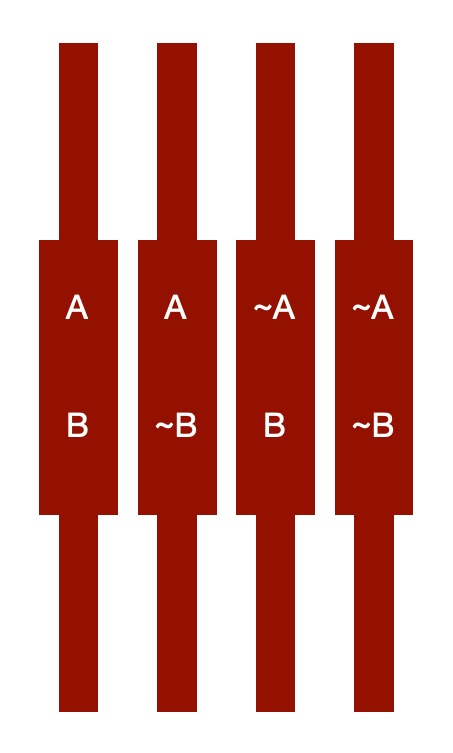

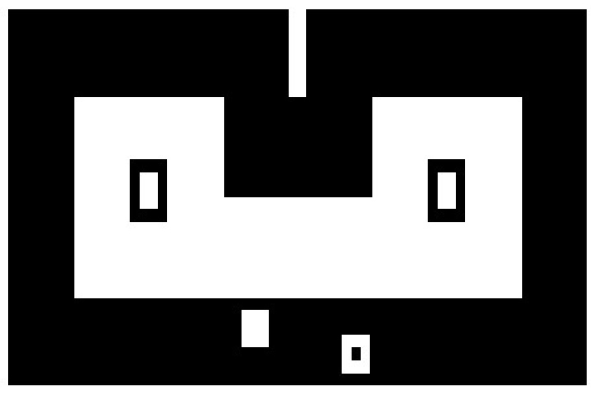

In the piano, a set of rods acted as truth tables, each one giving a true or false values for each variable. So imagine a piano that could deal with two variables A and B. Each of A and B can have two different values true and false, so there are four possibilities (so four rods):

- (A, B);

- (A, NOT B);

- (NOT A, B);

- (NOT A, NOT B)

where we write A to mean the assertion A is true and NOT A (or ~A in the picture) to mean A is false. Each rod represents a possible state of the world.

Let’s look at a simple example. Suppose A stands for the statement “Paul is a programmer” and B stands for “Safia is a programmer”, then the possibilities (if we know no specific facts) are

- (Paul is a programmer, Safia is a programmer) : (A, B)

- (Paul is a programmer, Safia is NOT a programmer) : (A, NOT B)

- (Paul is NOT a programmer, Safia is a programmer) : (NOT A, B)

- (Paul is NOT a programmer, Safia is NOT a programmer) : (NOT A, NOT B)

Each rod in Jevon’s piano had one of the possibilities on, so each rod represented a possible state of the world being reasoned about. At the start all the rods were visible, showing that nothing specific was yet known.

The point is that these represent all possible states of the world about Paul and Safia and whether they are programmers or not. If we know nothing more then all we can say is that all the pairs of facts are a possibility: all are possible states of the world.

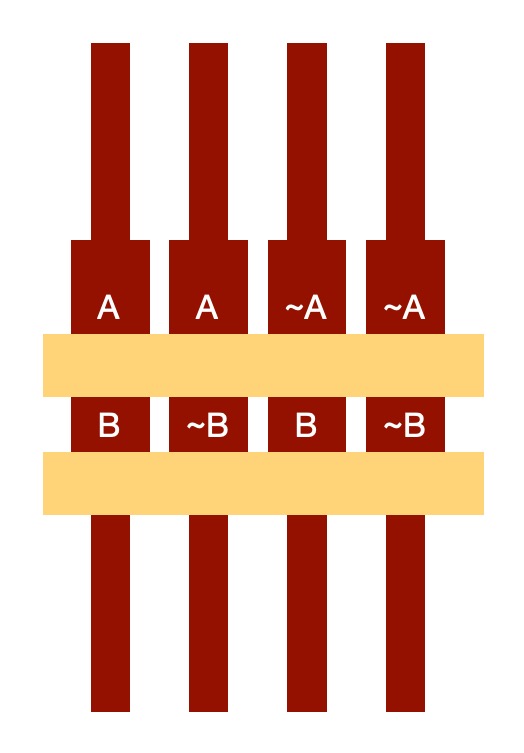

The piano worked by essentially leaving displayed or hiding each rod’s state as new facts were keyed in. (See the video at the end which includes a detailed explanation by expert David E Dunning on the detail of how it did this step by step). Initially all the possibilities are displayed as above. If we add a new fact that we have discovered or wish to assume, say that “Safia IS a programmer” (in terms of the piano, press the B key corresponding to the fact B is true), then doing so removes all states of the world where Safia is NOT a programmer. The piano, therefore, hides all the rods that include the assertion representing “Safia is NOT a programmer” (all those with (NOT B) on them) . We are left with two alternatives:

- (Paul is a programmer, Safia is a programmer) : (A, B)

- (Paul is NOT a programmer, Safia is a programmer) : (NOT A, B)

The mechanics of the machine meant that those facts would remain a possibilities (reading down the rods) but pushing the keys for that assertion would have moved the other rods, so hide their state. In doing so, the piano has deduced from the fact B that the possible conclusions are A AND B is true or NOT A AND B is true.

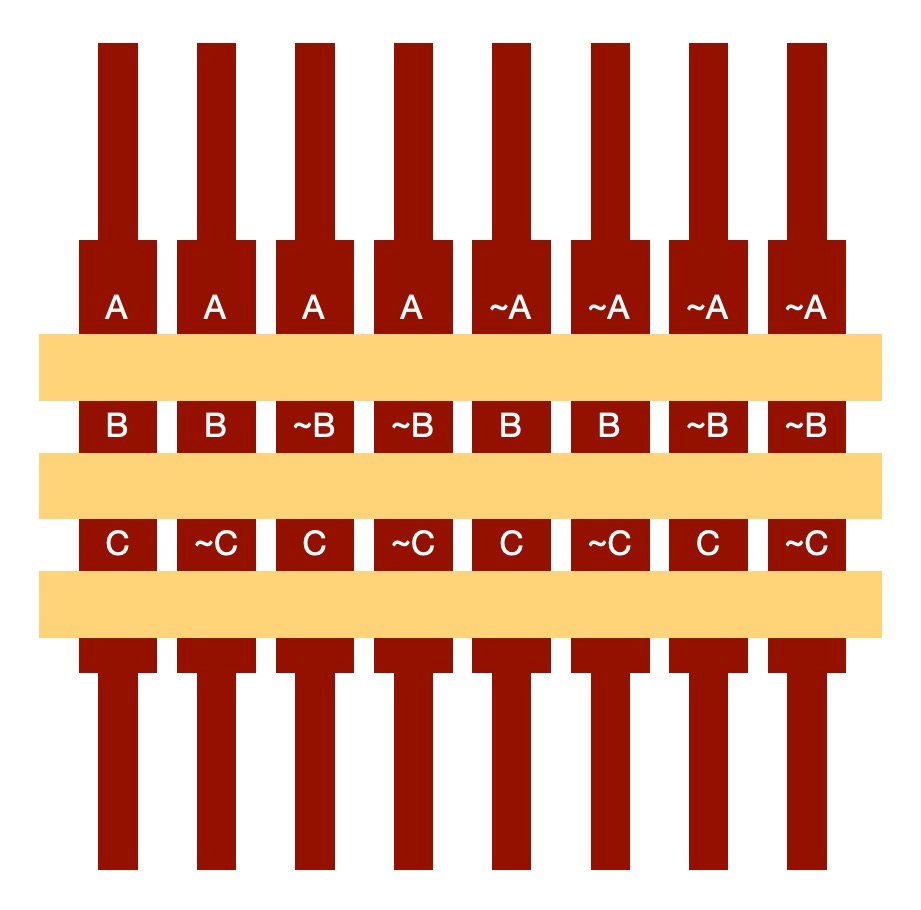

With three variables instead of two the machine would be able to deal with more complex situations – there are then 8 possibilities so 8 rods representing the 8 different states. .

Let A represent superheroes, (so NOT A represents those people who are not superheroes), B represents those people who fight crime and C with a person being Ghost Girl. Suppose we are considering some, at the moment, random person we know nothing about. The possibilities about them are:

- (Is a superhero, does fight crime, is Ghost Girl) : (A, B, C)

- (Is a superhero, does fight crime, is NOT Ghost Girl) : (A, B, NOT C)

- (Is a superhero, does NOT fights crime, is Ghost Girl) : (A, NOT B, C)

- (Is a superhero, does NOT fight crime, is NOT Ghost Girl) : (A, NOT B, NOT C)

- (Is NOT a superhero, does fight crime, is Ghost Girl) : (NOT A, B, C)

- (Is NOT a superhero, does fight crime, is NOT Ghost Girl) : (NOT A, B, NOT C)

- (Is NOT a superhero, does NOT fights crime, is Ghost Girl) : (NOT A, NOT B, C)

- (Is NOT a superhero, does NOT fight crime, is NOT Ghost Girl) : (NOT A, NOT B, NOT C)

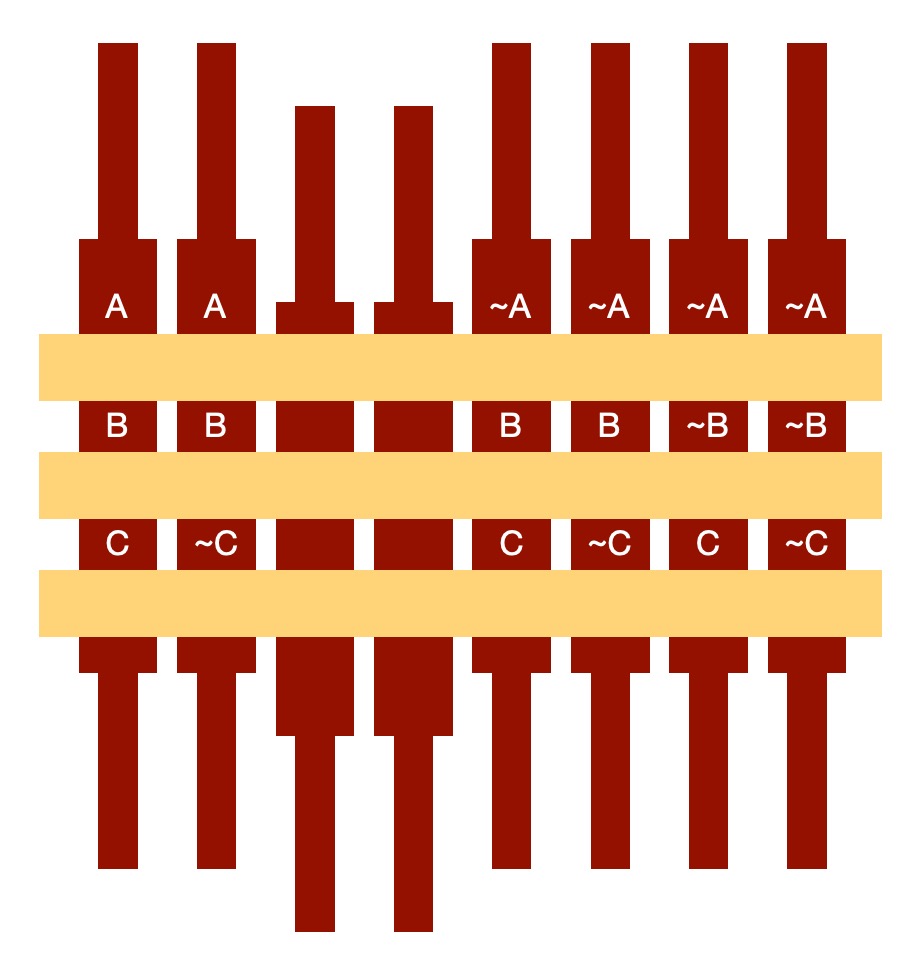

If we put the fact about them into the piano that ALL superheroes fight crime (ALL A are B) then we remove all rods where A is true but B is different so false (a superhero who doesn’t fight crime) as in this world, that is impossible.

- (Is a superhero, does fight crime, is Ghost Girl) : (A, B, C)

- (Is a superhero, does fight crime, is NOT Ghost Girl) : (A, B, NOT C)

- (Is NOT a superhero, does fight crime, is Ghost Girl) : (NOT A, B, C)

- (Is NOT a superhero, does fight crime, is NOT Ghost Girl) : (NOT A, B, NOT C)

- (Is NOT a superhero, does NOT fights crime, is Ghost Girl) : (NOT A, NOT B, C)

- (Is NOT a superhero, does NOT fight crime, is NOT Ghost Girl) : (NOT A, NOT B, NOT C)

Then we add the fact that Ghost Girl is a superhero (C is a A) so remove all those rods where Ghost Girl is not a superhero (ie NOT A, C):

- (Is a superhero, does fight crime, is Ghost Girl) : (A, B, C)

- (Is a superhero, does fight crime, is NOT Ghost Girl) : (A, B, NOT C)

- (Is NOT a superhero, does fight crime, is NOT Ghost Girl) : (NOT A, B, NOT C)

- (Is NOT a superhero, does NOT fight crime, is NOT Ghost Girl) : (NOT A, NOT B, NOT C)

We have deduced (the first possible state) that if the person we are interested in is Ghost girl then she is a superhero. We are also left with other possibilities too. If the person we are considering is not actually Ghost Girl then they may or may not fight crime and may or may not be a superhero!

If we add in an additional fact that the person we are thinking of IS actually Ghost Girl then we remove those extra rods so possibilities and get

- (Is a superhero, does fight crime, is Ghost Girl) : (A, B, C)

Ghost Girl is a superhero who does fight crime! We knew she was Ghost Girl and was a superhero but using the piano we have now deduced that she does fight crime. The machine has deduced the syllogism we gave at the start.

IF ALL superheroes fight crime AND

Ghost girl is a superhero

THEN

Ghost girl fights crime.The actual piano dealt with 4 variables (A, B, C, D) so had 16 rods representing the 16 different combinations. It also included keys to indicate the end of a conjecture, a key for IS A, and more to allow specific assertions to be input. The mechanism then hid rods automatically based on the facts entered. To use it, you did as we did: create a table of what A, B, C and D stand for (this is done outside the machine), enter the facts you want to reason about, and it then displayed all the possible states that remained in terms of A, B, C and D. Then, by seeing what each of the variables stood for in the table, you could convert that answer back into a deduced fact about the real world that you were interested in.

Amazingly, (after a first failed attempt) it did work. It is similar in idea to modern day theorem provers which are used to verify properties of safety-critical computer designs that must npot have bugs. Of course, being small and woody, the logic piano couldn’t solve every thing but then it turns out that was always an impossible dream. Even modern computers (and human mathematicians) have fundamental limits in what they can do (which is another story). The logic piano was a rather amazing, if woody, start to the area of automated theorem proving, though.

– Paul Curzon, Queen Mary University of London

Make a paper logic piano

Here is a kit to make a paper or card logic piano of your own (actually more like Jonons’ logic abacus the piano was a mechanised version of):

More on …

- Theory, Logic and Deduction

- Superhero Syllogisms

- Jevons book describing the logic piano [EXTERNAL]

- The Logic Piano at the History of Science Museum, University of Oxford [EXTERNAL]

Watch…

- A Purely Mechanical Form

- A Talk by David E Dunning at the Imagining AI conference about William Stanley Jevons and the logic piano including at the end a more detailed explanation of how pressing keys actually caused rods to by hidden in a series of steps. See also his article about it for the Computer History Museum.

Magazines …

Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish a new post to the CS4FN blog.

This blog is funded by EPSRC on research agreement EP/W033615/1.