A short story by Rafael Pérez y Pérez of the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, México translated from the original Spanish by Paul Curzon, Queen Mary University of London

(From the archive)

Divinity, all the gods and all the forces that man fails to understand, are sources of inspiration, a supreme gift which can be introduced in the heart or movement of men to make them a yoltéotl, a “heart deified”. (Miguel León-Portilla, The Old Mexican, Mexico: FCE, 1995 page 180)

Part I

Allow me a moment, Your Excellency. Now that I’m older, it’s hard to remember. But don’t worry, I will tell the whole story so that your priests can record it.

It all started that afternoon, on the day of Huey Tozoztli, just before the celebration to the maize goddess Centéotl. On the horizon you could see large pools of blood – the result of the endless struggle of the gods maintaining order in the cosmos – which, when mixed with the clouds and rays of sunshine on the background blue of the universe, drenched the sky with reddish, orange and yellow. As usual, I spent most of my free time watching everything that went on in Tlatelolco market.

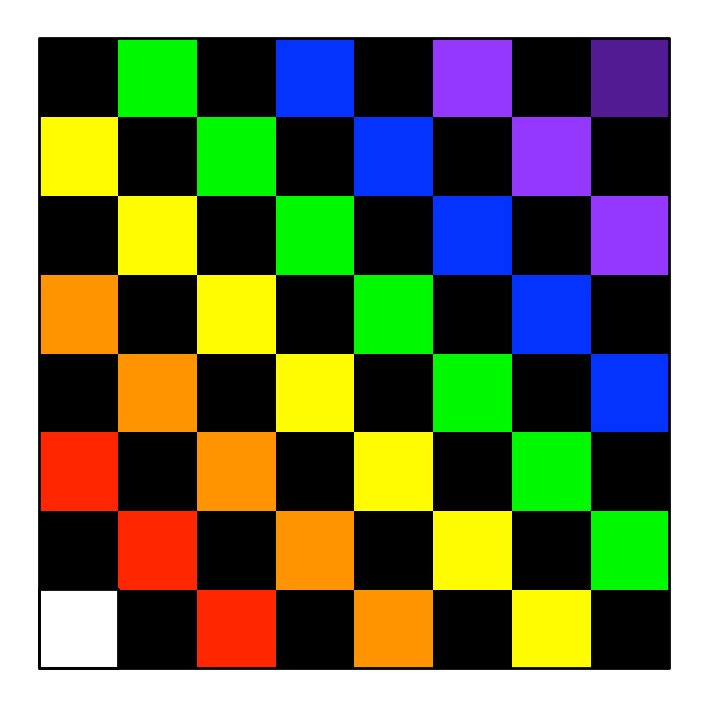

What most caught my attention amongst that huge convergence of smells, sounds and forms were grasshoppers; not only lovely to eat roasted on a tortilla, but also alive and full of dynamism, sometimes in the air and sometimes on the floor, sometimes in flight and sometimes sluggishly bound to the Earth – watching me. I was mesmerised for hours. I would line them up in rows of three insects, each row identified by a symbol and each grasshopper with its own number. I then watched the various patterns that arose when some reacted and tried to flee, “grasshoppers 1 and 3 in the first row jumped, while grasshopper 2 did not move.” Sometimes they were impossible to control!

That afternoon I came across Donají, the daughter of a famous Jaguar Knight. She wore a shawl across her shoulders so that you could barely see the long necklace of seashells hanging from her neck that, all tangled up, reached to just above her ankles. To see her made my heart begin to beat so, so fast! Although it was not the first time I had seen her, I had never had the opportunity to introduce myself. I stood beside her, but my mouth failed to produce a sound. No doubt she noticed my nervousness. I spent anxious moments just stuttering, until I said, ‘I’m Tizoc’. A grin spread across her face and she continued on her way without a word. She had ignored me! I felt humiliated. Who was Donají to treat me that way! I wanted to run and hide. Despite her arrogance, I felt a great attraction to her; I promised that one day I would show her who Tizoc really was and how wrong she was to treat me that way.

Part II

Several moons passed when one morning I woke up to hear a terrifying story: Donají had been kidnapped by a thug who was sentenced to death! A search was immediately organised, directed by her father, the great Jaguar Knight, which everyone joined. Eight units were formed. I was assigned to the group that went to Coyoacan. Once there, the warrior commanded us to spread out throughout the area in pairs to speed the search of the area. Because of my youth and inexperience I was appointed as an assistant to Sayil, a retired warrior of the Mexican army. We spent the first night by a stream. While looking for some dry branches to make a fire, I kept wondering how Donají would be feeling. After eating some fruit and roasted snake, I decided to distract myself and I started to enjoy my favourite pastime: watching the world! I was absorbed by a group of fireflies: while flying they would disappear without a trace only to then appear from nowhere. They formed groups of flying dancers in the darkness, following the rhythm of imaginary drums with lit torches plugged into their bodies. It seemed like a ceremony executed by priests in honour of some deity. I was completely immersed in my thoughts, admiring the ritual, when I discovered something surprising: fireflies and crickets share an essence! Grasshoppers jump or stand still on the ground; the flying fireflies were lit or unlit. In both cases, part of their behaviour can be described in terms of two states: jumping or landing; lit or unlit. It was what the priests called the divine essence! I was completely absorbed in my thoughts, when a voice interrupted me:

– ‘Tizoc, are you all right?’, asked Sayil.

– ‘I’m watching the fireflies: I want to see what they can communicate to me’, I replied.

– ‘Communicate?’

– ‘See how some fireflies are lit and others are off. Imagine that if two fireflies flying next to each other are on. We are receiving the message: ‘We are happy’. Now, imagine that we have three fireflies, one lit, then another lit but the third not lit. They are wanting to confess to us: “Walk to the lake and you will find a basket full of cocoa”. We both laughed. I continued: ‘We should call this “the behaviour of the two states.”‘

– ‘I once saw a fortune-teller use the same method’, commented Sayil yawning. I listened intently. ‘He had three figurines made of opossum bones representing Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli, the malevolent God of Venus, who fires darts both at people and at other objects, causing bad things to happen. People asked the fortune-teller questions like “Will the harvest be good this year?” Then he put the figurines in a jar and tossed them: he predicted the future based on how many landed on their back and how many fell on their front – or in terms of fireflies, how many were lit and how many unlit – together with the order in which they fell.’

Sayil’s words left me paralysed for a moment: the priests communicated with the deities through messages made of patterns represented as two states! I was excited and shouted:

– ‘I knew that the grasshoppers and fireflies were connected with the gods!’

Sayil didn’t really understand what I was saying, and he was too tired to ask. A few minutes later he fell asleep, though I only went to sleep late in to the night.

Very early the next morning we continued the search. In some thickets we found the necklace of seashells that I had seen Donají wearing in the market. After a while we came to a crossroads; Sayil, despite all his experience, was not sure which way to turn. So I suggested:

– ‘Let’s ask the gods which path is the right one’.

– ‘What do you mean?’

I pulled out a small leather pouch containing three round stones, which the night before I had painted on one side with green dye made from vegetable plants. I had left the other side its natural grey colour. I put them into a jar and threw them so they landed in a line and said:

– ‘If the green painted side is facing up, it is equivalent to a firefly turned on. If the grey side is exposed it is equivalent to an off’.

– ‘You want to play the soothsayer? We don’t know how to interpret the gods!’

– ‘But we can ask them to guide us’, I said.

– ‘How?’ The warrior asked impatiently.

– ‘Assign to each of the five directions of the universe, a pattern in the stones. Implore the gods for their advice and throw them. I am sure the pattern representing the direction that arises will give us the correct way to go. It is the same as it was when the soothsayer asked about the harvest.’ Sayil didn’t seem to understand my idea, so I continued saying: ‘the combination of stones grey-grey-grey represents the centre, that is, stay where we are. Grey-grey-green means walking towards where the nomadic people are, to the north. Grey-green-grey means walk towards the Zapotec lands in the South. Grey-green-green, means walk to where Tonatiuh, the Sun God emerges, and green-grey-grey means walk in the opposite direction.

I clearly remember that Sayil thought this seemed a silly idea. However, time was short and we didn’t have another way to decide which road to take. So, rather than do nothing he decided to go with my idea:

– ‘How will we know how many steps to go?’ He asked now even more impatiently.

– ‘Once we know the direction we go back to throwing stones. There are eight possible patterns.’

– ‘How do you know?’

– ‘Believe me. I spent a long time watching the grasshoppers jumping! Each pattern represents a number from zero to seven. Then, if we get the pattern 0 we move 20 steps; if pattern 1 appears move 40 steps; if 2 appears we move 80 steps, and so on.

– ‘Tizoc, I think you’ve lost your mind’, Sayil said desperately.

– ‘Trust me. So the first throw will be a statement that tells us where to walk. The second will tell us the number of steps forward. We continue doing this until the instruction appears as the green-green-green pattern, which will mean we have received all the directions.

I put the pebbles in a jar, prayed to the gods for help and threw:

– ‘Grey-green-grey. We have to move towards the land of the Zapotecs! Now, let’s see how many steps: green-green-green, it means …2,560 steps’. I went back to throwing the stones: ‘then we head towards where Tonatiuh rises and walk … 640 steps’.

– ‘Tizoc, are you going to spend all morning throwing stones while Donají is about to die? When are you going to finish this?’

– ‘When the gods tell me to.’

I threw the stones again and to Sayil’s surprise the green-green-green combination appeared: end of the message! We followed the instructions sent by our gods and even though I hadn’t been able to make Sayil believe, we did finally find the hideout of the kidnapper.

Donají was inside a small cave whose entrance was blocked; on seeing her my heart began to pound! Unfortunately, a surprise awaited us, we saw that the kidnapper had two accomplices: this complicated things greatly as we would need support for the rescue. We decided Sayil would go for help while I stayed to monitor the situation, so without wasting more time my partner set off.

Near dark I tried to get as close as possible to let Donají know that she would soon be rescued; I was sure she would be glad of my presence. Unfortunately, one of the thugs discovered me. I was immediately thrown into the cave:

– ‘What are you doing here?’ She asked, shocked to see me.

– ‘Donají! Don’t worry; help will be here soon’, I replied, stuttering again! She immediately realised that there was no else out there to rescue us. Her face contorted in anger and she shouted:

– ‘Why didn’t you go in search of my father instead of getting caught!’

She burst into a flood of tears, weeping and weeping for a long time until she finally fell asleep. I felt a failure. But I swore by the gods to get her out of there!

I tried to stay calm when the three thugs approached: first the leader, who was very young; then a burly one, who seemed a bit of an idiot; and finally a slave who, I suppose, had simply taken the opportunity to get away. The idiot and slave dragged me out of the cave and tied me by my wrists to a tree branch. The noise woke up Donají. I was very scared. The leader began to punch me in the stomach. He wanted to know how many people knew the hiding place. I will never give him the information he wants I told myself. He repeatedly punched me until he grew bored. Then he took a leg of venison, clutching the hoof tightly with both hands he crashed it into my nose! I thought I would die! Donají screamed desperately until finally they took me back to the cave.

From the twisted material of her shawl she made presses and bandages. She wiped my face carefully and all my wounds trying to stem the bleeding. She spent the whole night giving me water to drink and mopping my brow. I will never forget her courage and fortitude! Unfortunately, the next morning, things got worse:

– ‘Tizoc, we have to get up.’

– ‘Are we leaving? Where are we going?’

– ‘I overheard them say that we will go to a valley that is a half-day along the path to Totolhuacalco. The sky is cloudy, so surely it will rain later. If we start today, there is no way anyone will work out where we have gone.’

The situation was critical and I had to come up with something before we left …

Part III

The next day, we were already installed in the new hideout, watching our new surroundings when Donají asked:

– ‘What are your thinking about, Tizoc’?

– ‘The gods have sent me a vision’, I answered.

– ‘A vision? What do you mean?’

– ‘Listen: today, at dawn, Sayil arrived with reinforcements to our former hideout, but was surprised to find it abandoned. Now how could he find us? The rain had washed away all traces of our departure. How would he explain to the great Jaguar Knight that he had lost the trail of his daughter? Sayil and the others, now desperate, reviewed the surroundings and, entering the cave where we had stopped, discovered some strange signs.’

– ‘Do you mean the symbols you drew on the wall?’

– ‘That’s right! One of the soldiers said “It looks like a big fly”. Sayil immediately understood the meaning of the drawings and shouted “No, it’s a firefly!”‘

– ‘What are you talking about?’ Donají asked confused.

At that moment we heard loud cries and Sayil, along with a group of Mexica warriors, began the attack on the new hideout. The slave tried to flee, but was captured immediately; the idiot resisted, but the warriors took a stone and split his head in two; the leader tried to attack Donají, but Sayil grabbed him and strangled him. In just a few moments it had all ended for the trio! Donají wept with happiness. My plan had worked! I was ecstatic! I had finally shown to Donají my worth! It was an unforgettable day for me.

How did they find us? Let me explain, Your Excellency, just let me drink a little water … thank you. It all happened as follows. That day I had to devise a way to communicate to Sayil where we were being taken. I was well aware that our lives depended on it, but was paralysed. Unexpectedly, I heard what I thought was a message from the gods: grasshoppers singing! Two states! That was the solution! I estimated the number of steps required to travel half a day along the Totolhuacalco path and using the same code that Sayil and I had used to find Donají, I left the approximate position of our new location on the cave wall! The kidnappers never suspected that those drawings were instructions of how to find us. So Sayil was given the key to finding us! … Thank you, Your Excellency! I know it was ingenious. Thank you very much. Am I sorry? … What do you mean? “What happened to Donají?”… Your question opens old wounds. I think that you and your brothers would never understand what I mean when I say that, although I never saw her again, my heart was forever linked to hers. I’m tired. With your permission, I would like to go to sleep now.

Two states: divine essence! What can they teach us? What wonders can man create with them? Because while enduring the fifth sun, hearts will be deified. (Tizoc)

The End.

More on …

Related Magazines …

EPSRC supports this blog through research grant EP/W033615/1.