Digitally stitching together 2D photographs to visualise the 3D world

Imagine you’re the costume designer for a major new film about a historical event that happened 400 years ago. You’d need to dress the actors so that they look like they’ve come from that time (no digital watches!) and might want to take inspiration from some historical clothing that’s being preserved in a museum. If you live near the museum, and can get permission to see (or even handle) the material that makes it a bit easier but perhaps the ideal item is in another country or too fragile for handling.

This is where 3D imaging can help. Photographs are nice but don’t let you get a sense of what an object is like when viewed from different angles, and they don’t really give a sense of texture. Video can be helpful, but you don’t get to control the view. One way around that is to take lots of photographs, from different angles, then ‘stitch’ them together to form a three dimensional (3D) image that can be moved around on a computer screen – an example of this is photogrammetry.

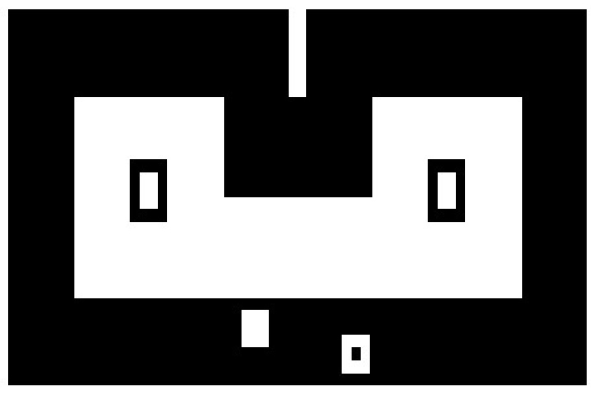

In the (2D) example above I’ve manually combined three overlapping close-up photos of a green glass bottle, to show what the full size bottle actually looks like. Photogrammetry is a more advanced version (but does more or less the same thing) which uses computer software to line up the points that overlap and can produce a more faithful 3D representation of the object.

In the media below you can see a looping gif of the glass bottle being rotated first in one direction and then the other. This video is the result of a 3D ‘scan’ made from only 29 photographs using the free software app Polycam. With more photographs you could end up with a more impressive result. You can interact with the original scan here – you can zoom in and turn the bottle to view it from any angle you choose.

You might walk around your object and take many tens of images from slightly different viewpoints with your camera. Once your photogrammetry software has lined the images up on a computer you can share the result and then someone else would be able to walk around the same object – but virtually!

Photogrammetry is being used by hobbyists (it’s fun!) but is also being used in lots of different ways by researchers. One example is the field of ‘restoration ecology’ in particular monitoring damage to coral reefs over time, but also monitoring to see if particular reef recovery strategies are successful. Reef researchers can use several cameras at once to take lots of overlapping photographs from which they can then create three dimensional maps of the area. A new project recently funded by NERC* called “Photogrammetry as a tool to improve reef restoration” will investigate the technique further.

Photogrammetry is also being used to preserve our understanding of delicate historic items such as Stuart embroideries at The Holburne Museum in Bath. These beautiful craft pieces were made in the 1600s using another type of 3D technique. ‘Stumpwork’ or ‘raised embroidery’ used threads and other materials to create pieces with a layered three dimensional effect. Here’s an example of someone playing a lute to a peacock and a deer.

A project funded by the AHRC* (“An investigation of 3D technologies applied to historic textiles for improved understanding, conservation and engagement“) is investigating a variety of 3D tools, including photogrammetry, to recreate digital copies of the Stuart embroideries so that people can experience a version of them without the glass cases that the real ones are safely stored in.

Using photogrammetry (and other 3D techniques) means that many more people can enjoy, interact with and learn about all sorts of things, without having to travel or damage delicate fabrics, or corals.

*NERC (Natural Environment Research Council) and AHRC (Arts and Humanities Research Council) are two organisations that fund academic research in universities. They are part of UKRI (UK Research & Innovation), the wider umbrella group that includes several research funding bodies.

Other uses of photogrammetry

Examples of cultural heritage and ecology are highlighted in the post but also interactive games (particularly virtual reality), engineering and crime scene forensics and the film industry use photogrammetry, an example is Mad Max: Fury Road which used the technique to create a number of its visual effects. Hobbyists also create 3D versions (called ‘3D assets’) of all sorts of objects and sell these to games designers to include in their games for players to interact with.

Jo Brodie, Queen Mary University of London

More on …

- Art Touch and Talk Tour Tech

- 3D models in motion

- Automated 3D Capture: High Resolution Imaging of Cultural Artefacts (2024) Festival of Futures, at Lancaster University [EXTERNAL]

- What is photogrammetry? (12 November 2021) Great Barrier Reef Foundation

“What it is, why we’re using it and how it’s helping uncover the secrets of reef recovery and restoration.” [EXTERNAL]

Careers

This is a past example of a job advert in this area (since closed) for a photogrammetry role in virtual reality.

Also see our collection of Computer Science & Research posts.

Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish a new post to the CS4FN blog.

This blog is funded by EPSRC on research agreement EP/W033615/1.