Past CS4FN articles have explored object-oriented programming through self-aware pizza and Strictly Come Dancing judges. But, if you’re one of those people who like to learn visually, it can be challenging to imagine what an object or class looks like. This article will hopefully help you to both think more about what makes this paradigm so useful as well as to give you a way to visualise objects.

To begin this adventure, I’d like to introduce Ada. Ada is an example of the newly discovered species egghead. Every egghead has very distinctive hair and eye colours. For example, Ada’s hair is a delightfully bright pink, and their eyes, a deep red. Despite their appearance, the egghead has a vicious roar intended to ward off predators, or indeed poachers.

Classes

As computer scientists, we might want to represent different eggheads in a program, but we don’t really want to store information about the eggheads with a written description or an image, because this would be harder than need-be for a computer to ‘understand’ (or rather to process as they don’t understand as such). Instead, we can store lots of individual features together, so that the computer can find out exactly what it needs from each egghead.

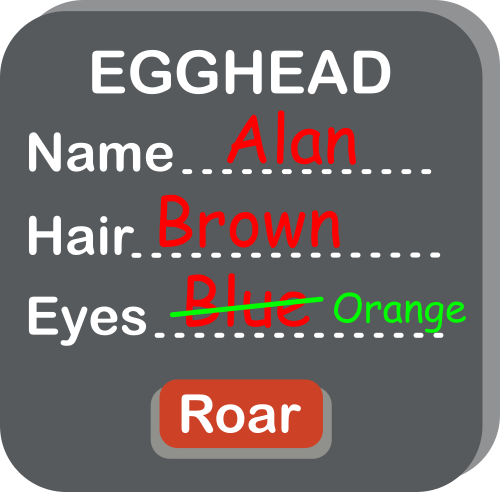

One way to achieve this is by using a class. A class is a template which contains spaces for us to fill in details for the thing we want to represent. For the egghead, we might want to store data about their name, hair colour, and eye colour – then we can fill in the template for each of the eggheads we find. These individual features are often called attributes. In a program, these attributes would be represented with variables: a place where a value, a piece of data, is stored. We can visualise a class therefore as a box with gaps to fill in for the attributes like the one on the left.

From this image, you will see alongside the attributes, we also have an image of a button for roaring. As well as storing attributes, we also define behaviours. These are actions that we can perform on the thing being represented. We visualise any behaviour as such a button. For this example, we could imagine that pressing this button might provoke the egghead causing them to roar. In programming, a behaviour is represented by a procedure, some pre-defined code that when executed makes something happen. A button that causes something to happen is a simple way to visualise such procedures.

A key point to realise is that this class is simply a template – it isn’t storing any information, nor will the roar button work. We have no actual eggheads yet… That is where objects come in.

Objects

You may have noticed that I have been using the word thing to represent the actual thing (here eggheads) that we are representing with the class. This is to avoid using the word object, which has its own special meaning, in, you guessed it, object-oriented programming. If we want to actually use our class, we need to make an instance. That just means filling in the relevant details about the specific egghead we want to store. This instance is called an object.

Let’s imagine we want to store a representation of Ada in our program. We would take an instance of the Egghead class and fill in their details. The resulting object would represent Ada, whereas the class we started with represents all and any egghead that might ever exist. Below, you can see the objects for Ada and some of Ada’s friends; Alan and Edsger. We still visualise objects as boxes, just like classes, except now the gaps are all filled in.

We (or a computer) could even take the given features of Alan and Edsger and generate an image of what they might look like. We have everything we need here to create something that looks and behaves like an egghead. This method of storing data means that a program can take whatever information it might want directly from the object. Likewise, it can do the equivalent of pressing the roar button and make each individual egghead roar.

Hiding the Details

One thing we should consider while making the class is the integrity of the data. In its current form, any other part of our program, or another program using our class, can directly edit the attributes stored. Another part of the program (perhaps representing a virtual world for a virtual egghead to live in) might accidentally change the eye colour attribute for Alan, for example. This wouldn’t change Alan’s actual eye colour (which couldn’t happen anyway!), so our data would then be wrong. We can’t have that!

We can fix this by hiding the eye colour from the rest of the program, so it is stored within the object, but not accessible outside of it. But we still need a way for the program to read it: for this we use a button in our picture of the Egghead class. The existence of the eye colour attribute can then only be seen by other parts of the program by a procedure that gets the eye colour. No similar procedure is given for changing the eye colour, so there is no way to do it by mistake. Let’s build this new version of our class.

This concept of hiding details is sometimes called encapsulation or information hiding, but computer scientists disagree about what these terms refer to exactly. Encapsulation is broader in its meanings, whereas information hiding is closer to what we are trying to do here. This video by ArjanCodes (see below) explains this distinction further.

We could change our class to include this concept for the name and hair colour, too. Whilst it is entirely possible for these attributes to change, it turns out that it is a good idea to hide them too: so hide name and use SetName and GetName buttons. That allows us to control the type of data we have going into that attribute (for example, checking the given name isn’t a number, which as all egghead names are made of letters would be a mistake).

Where next?

Now we have a class that represents all eggheads, we can store the details of any new egghead efficiently and safely. Hold on… some last-minute breaking news: scientists have found a new sub-species of egghead they are calling a rainbow egghead. All rainbow eggheads have rainbow hair, and a unique roar. Next time, we’ll use the concept of inheritance to give a more efficient way to write programs that store information about eggheads.

Daniel Gill, Queen Mary University of London

More on …

Watch…

- What is encapsulation and information hiding [EXTERNAL]

Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish a new post to the CS4FN blog.

This blog is funded by EPSRC on research agreement EP/W033615/1.