(or how to stack properly)

We present a CS4FN exclusive (from our archive): a mathematical card trick contributed by TV celebrity mathematician, Johnny Ball. The BAFTA-winning father of radio DJ Zoë Ball is famous for his TV shows like Think of a Number, Think Again and Johnny Ball Explains All, plus numerous brilliant books on maths and science.

The trick is as follows, in Johnny’s words…

There is a very simple card trick that I often use, as I can get to the explanation very quickly. In fact, for a mathematically minded audience, they are already some way to working out why it works, as soon as it does work. It’s called the Two Wrongs Do Make a Right Trick.

Just memorize the top card of a pack; let’s assume it’s the 4 of Hearts. Hand the pack to someone and ask them to choose any smallish number (eg between 1 and 10), then to deal that number of cards face down. Then announce the next card dealt will be the 4 of Hearts. Oops – it isn’t? Get them to place all the dealt cards on top of the pack again. Now ask them to choose a number bigger than the first one, but not so big that we run out of cards (eg between 10 and 20). They now deal that number face down, and the next card dealt will be the 4 of Hearts. Oops – wrong again. Let’s now see if we can make two wrongs equal a right.

Place the cards back on top. Now ask for a last chance. Take the smaller number from the larger. They now deal that number face down, and the next card dealt is the 4 of Hearts. Success!

Why does it work?

Hidden in this distracting presentation, the tale of your mistakes played up for laughs, is some clever mathematics. It uses a magic technique called a stack, which is a set up sequence of cards in a known order. Sometimes magicians will put a pre-defined stack of cards, for example four aces, on top of the deck and do a false shuffle, and then be able to deal a wining poker hand because they know exactly what cards will be dealt. In this trick your ‘mistakes’ create the stack for you.

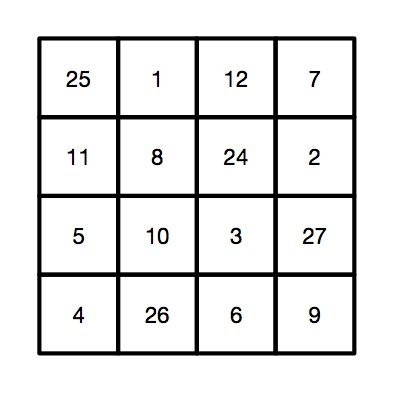

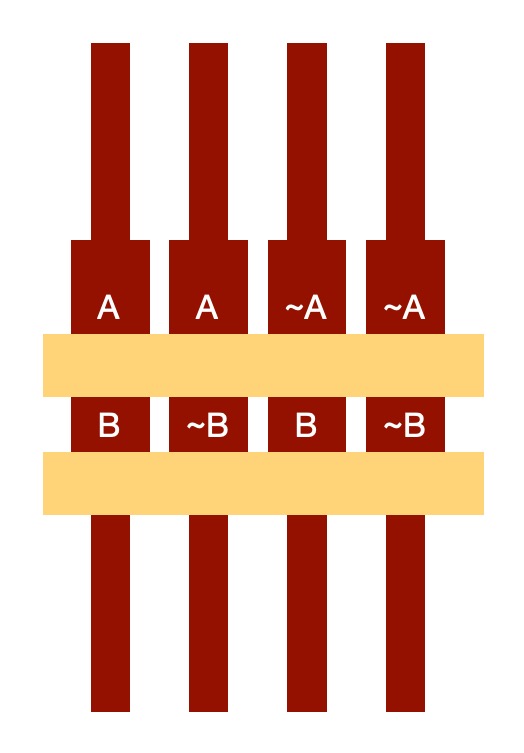

X stacks the deck

Starting with your known card on top (that’s your secret card), your spectator chooses a number from 1 to 10. Let’s call that number X. You deal down X cards so that the first card down is the secret card, next down is the second from the original top of the pile and so on. At the end of your count of X there are X cards on the table, with the secret card on the bottom. Oops, mistake number one. Don’t worry, you can regroup. Just place the mistaken card back on top of the pile of undealt cards, then stack those X dealt cards back on top, and your deck now looks like this from the top down: (X-1) indifferent cards, the secret card, and the rest of the pack.

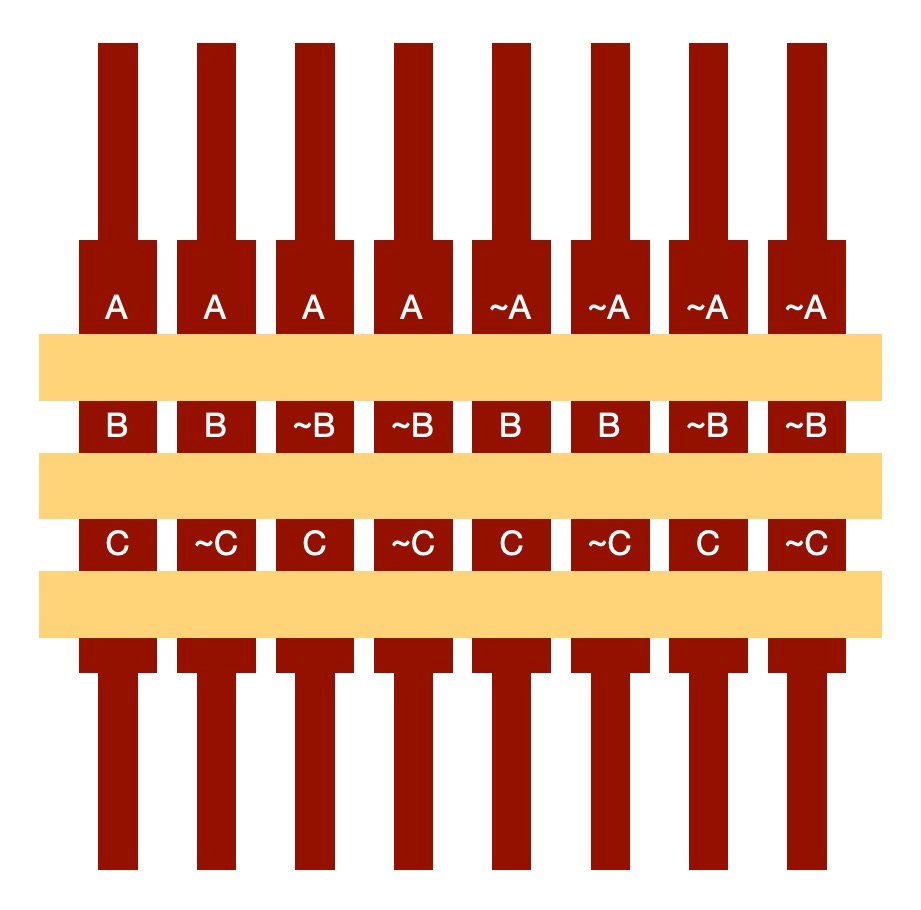

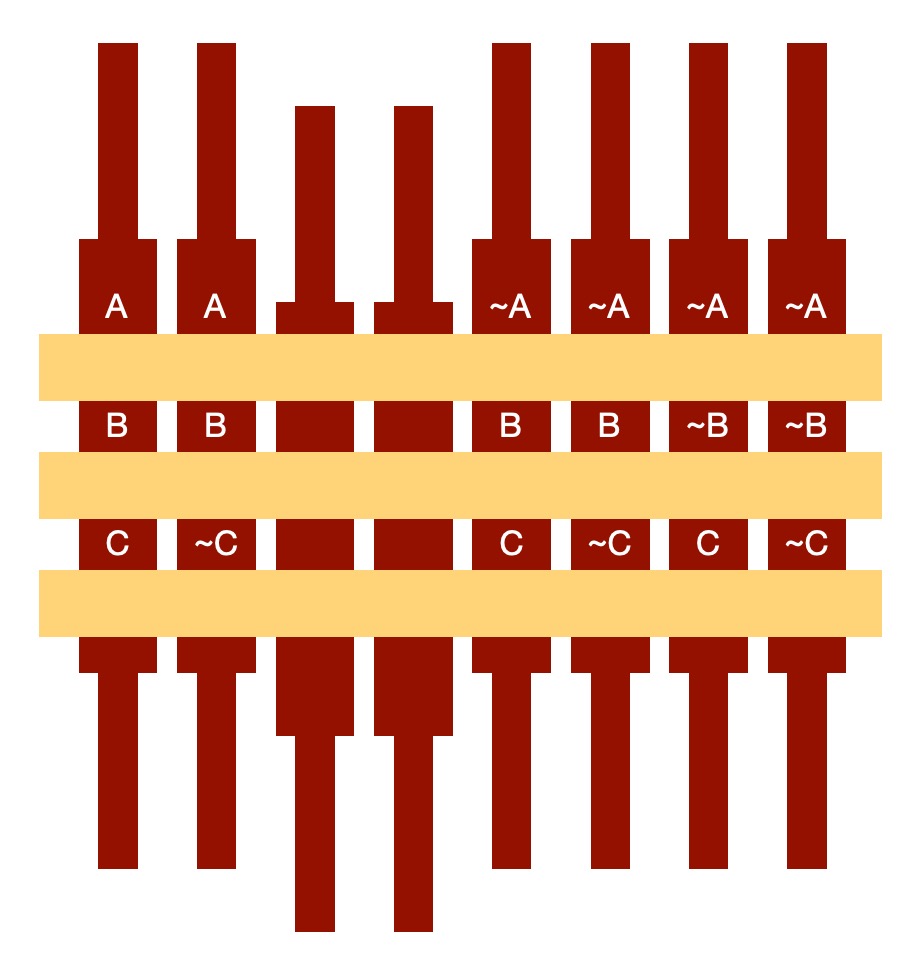

Y marks the spot

Second try – this time you ask for a bigger number, a number between 10 and 20. Let’s call that new number Y. Counting and dealing down Y cards, where number Y is bigger than number X, means that once Y cards are on the table you can reveal mistake two, oops again. But let’s ‘think of the numbers’ of the cards on the table. That pile has Y cards, and because we stacked the deck in the first phase the secret card is now at position X from the bottom of these Y cards, meaning it’s at position Y-X. Exactly the position in the stack to be revealed by the finale where you subtract X from Y and count down (oh wait, that’s another mathematical TV programme).

Think again – with some real numbers!

The algebra of Xs and Ys says it works, but to see this is true let’s test it and think of some specific numbers, say X=5 and Y=15. The first deal stacks the secret card at position 5 from the top. We then do the second deal of 15 cards, reversing as we go. Onto the table goes 1, 2, 3, 4, SECRET, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15. Pick up this pile and put it on top of the pack. The secret card is now in a new stack. From the top down it’s at 15, 14, 13, 12, 11, 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, SECRET, rest of pack. Now count down 10 cards from the top of this new stack (that’s X-Y = 15-5 = 10), dealing 10 cards from the final stack gives us 15, 14, 13, 12, 11, 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, and the next card is the SECRET card! Magic.

Proving algorithms work

A magic trick like this is what computer scientists call an ‘algorithm’: steps that if you follow them guarantee some result – here that your secret card is revealed. What we showed above is a logical, mathematical proof that the trick works. Now, programs are just algorithms (written in a programming language) so in the same way as we proved our trick works we can prove logically that a program we write always works too!

Even if you do do such a proof, it is also a good idea with software to do lots of testing too – putting in some values to check it works for specific cases too (lots more than the one example we checked). Doing that first can also help you come up with the proof.

Finale the stack pays off

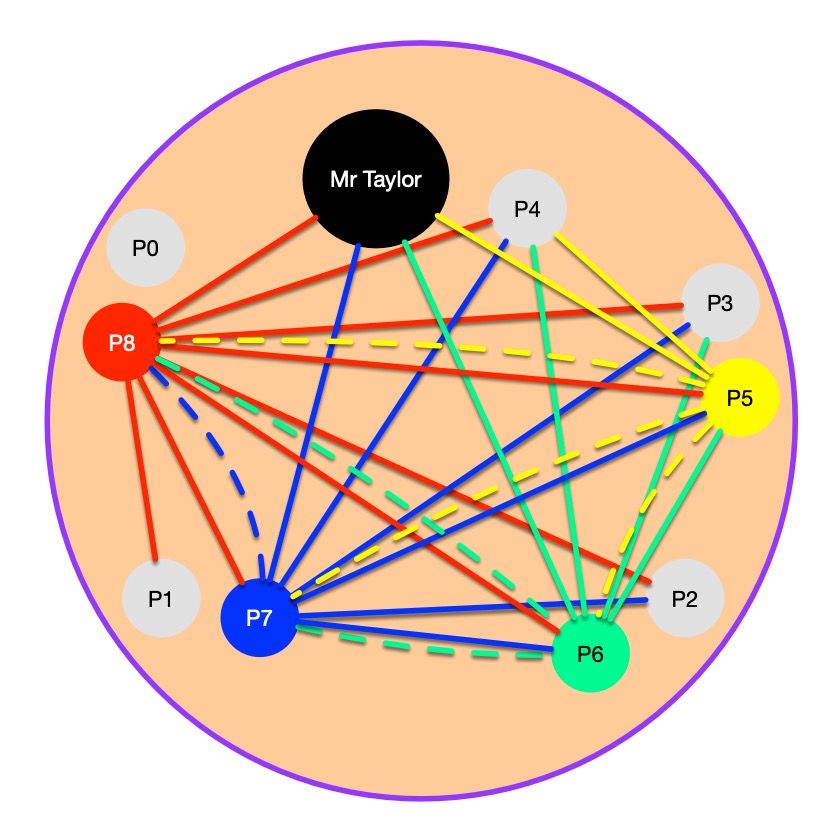

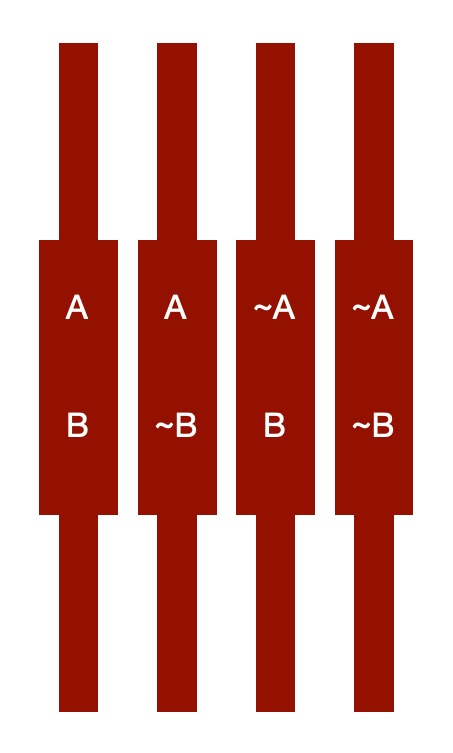

Stacks, in this case the series of cards in a given order, that you deal from the top of the pack, are also used in computer science, though the meaning is slightly different. It is a data structure, a place to store information, that works like a stack of chairs. You can add a chair or take one from the top of a stack of chairs but not from the middle, and its the same with adding and removing data in a computer science stack.

Computer scientists like to have ways of thinking of data, normally numbers in the computer memory, in such a way that they know where things are so they can use them when they need them. A stack is an example of what computer scientists call an abstract data type, a data structure with rules of how you add and remove data to and from it. The stack is a ‘container’ of data (or nodes if the things stored are more complex than just plain numbers, and link off to other parts of memory). Computer scientists do two basic things to stacks: they ‘push’ and they ‘pop’. In a push a new element is added to the top of the stack, and all those elements under effectively move down a place. It’s like adding those cards on top of the secret card. In a pop the top element is removed from the stack, and up jumps all the elements underneath, like dealing a card from the top of the deck. Your laptop and your mobile phone will have a stack somewhere in them. The software will be pushing and popping and doing lots of other clever computer science tricks to keep track of the information and how it’s moving around. The programmer will probably use even smarter things like stack pointers. These are a note for the computer to tell it what was last changed and where in the stack it was.

One too many?

One of the nastiest (and easiest to make) errors in computer software can come from something called a stack overflow. A program pops from or pushes to the top of the stack. That position in memory is kept track of using the ‘stack pointer’, which is just like a sign pointing to where the top of the stack is. So we push and pop from where the stack pointer is pointing changing the position of the pointer as we do. A stack normally has a fixed maximum size (like hitting the ceiling with a stack of chairs). A stack overflow is where you shoot off the end of the stack, so where you try to push a value on the stack when it is already full. It is like a magician counting past 52 cards. It can only end in tears. Sometimes this nasty trick is used by computer hackers to gain control of a computer system. Once the stack has been overshot, the computer surrenders. The software has literally lost its place, and the hackers can move in and take over.

Fortunately maths can come to the rescue by creating tests to ensure that the stack doesn’t pop its clogs or push up the daisies. Even better you can prove that the program controlling the stack (just an algorithm) never lets you overflow the stack in the same way that we proved our trick always works.

Let’s pop over and give the last word to Johnny

Ever ready to make things simple to understand and easy to do, Johnny points out:

You can reduce the trick to choosing just 1 and then 2 with just three cards, and show that the manoevring moves the top card down by the difference in numbers chosen.

Now why didn’t we think of that?

Peter W McOwan, Paul Curzon, Queen Mary University of London

but critically of course (and also inspiring us about Maths since we were kids), Johnny Ball

More on …

Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish a new post to the CS4FN blog.