Can a translation program make music? It turns out they potentially can – they can beatbox! In the future perhaps Artificial Intelligences will be able to do creative beatboxing the way human beatboxers do.

Beatboxing is a kind of vocal percussion used in hip hop music. It mainly involves creating drumbeats, rhythm, and musical sounds using your mouth, lips, tongue and voice. So how on earth can Google Translate do that? Well a cunning blogger worked out a way. Once on the Google Translate page they first set it to translate from German into German (which you could do then). Next they typed the following into the translate box: pv zk pv pv zk pv zk kz zk pv pv pv zk pv zk zk pzk pzk pvzkpkzvpvzk kkkkkk bsch; Then when they clicked on the “Listen” button to hear this spoken in German. Google translate beatboxed.

So how do programs like Google Translate that turn text into speech do it? The technology that makes this possible is called ‘speech synthesis’: the artificial production of human speech.

Originally, to synthesise speech from text, words are first mapped to the way they are pronounced using special pronunciation (‘phonetic’) dictionaries – one for each language you want to speak. The ‘Carnegie Mellon University Pronouncing Dictionary’ is a dictionary for North American English, for example. It contains over 125 000 words and their phonetic versions. Speech is about more than the sounds of the words though. Rhythm, stress, and intonation matter too. To get these right, the way the words are grouped into phrases and sentences has to be taken into account as the way a word is spoken depends on those around it.

There are several ways to generate synthesised speech given its pronunciation and information about rhythm and so on. One is simply to glue together pieces of pre-recorded speech that have been recorded when spoken by a person. Machine learning provides a new way to do it – machine learning programs are trained on vast amounts of recorded speech and learn the natural way humans speak from listening to humans actually speak. That gives a way to overcome the problems of just using pronunciation dictionaries.

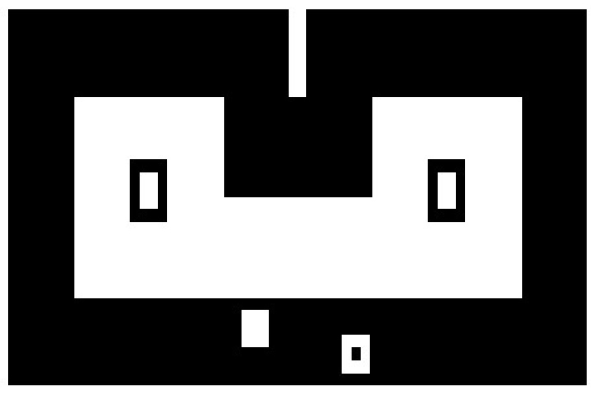

Another way uses what are called ‘physics-based speech synthesisers‘. They model the way sounds are created in the first place. We create different sounds by varying the shape of our vocal tract, and altering the position of our tongue and lips, for example. We can also change the frequency of vibration produced by the vocal cords that again changes the sound we make. To make a physics-based speech synthesiser, we first create a mathematical model that simulates the way the vocal tract and vocal cords work together. The inputs of the model can then be used to control the different shapes and vibration frequencies that lead to different sounds. We essentially have a virtual world for making sounds. It’s not a very big virtual world admittedly – no bigger than a person’s mouth and throat! That’s big enough to generate the sounds that match the words we want the computer to say, though.

These physics-based speech models also give a new way a computer could beatbox. Rather than start from letters and translate them into sounds that correspond to beatboxing effects, a computer could do what the creative beatboxers actually do and experiment with the positions of its virtual mouth and vocal cords to find new beatboxing sounds.

Beatboxers have long understood that they could take advantage of the complexity of their vocal organs to produce a wide range of sounds mimicking those of musical instruments. Perhaps in the future Artificial Intelligences with a creative bent could be connected to physics-based speech synthesisers and left to invent their own beatboxing sounds.

by the CS4FN team (adapted from the archive)

More on …

Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish a new post to the CS4FN blog.