Celebrating LGBTQ+ Greats

Thousands of programming languages have been invented in the many decades since the first. But what makes a good language? A key idea behind language design is that they should make it easy to write complex algorithms in simple and elegant ways. It turns out that logic is key to that. Through his work on programming language design, Peter Landin as much as anyone, promoted both elegance and the linked importance of logic in programming.

Peter was an eminent Computer Scientist who made major contributions to the theory of programming languages and especially their link to logic. However, he also made his mark in his stand against war, and support of the nascent LGBTQ+ community in the 1970s as a member of the Gay Liberation Front. He helped reinvigorate the annual Gay Pride marches as a result of turning his house into a gay commune where plans were made. It’s as a result of his activism as much as his computer science that an archive of his papers has been created in the Oxford Bodleian Library.

However, his impact on computer science was massive. He was part of a group of computing pioneers aiming to make programming computers easier, and in particular to move away from each manufacturer having a special programming language to program their machines. That approach meant that programs had to be rewritten to work on each different machine, which was a ridiculous waste of effort! Peter’s original contribution to programming languages was as part of the team who developed the programming language, ALGOL which most modern programming languages owe a debt to.

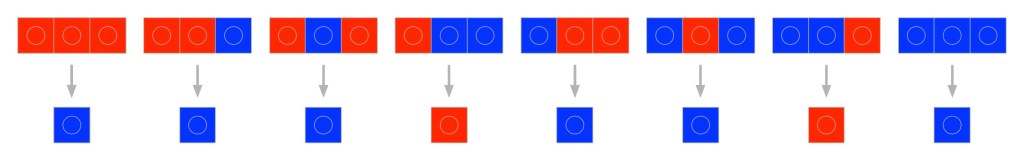

ALGOL included the idea of recursion, allowing a programmer to write procedures and functions that call themselves. This is a very mathematically elegant way to code repetition in an algorithm (the code of the function is executed each time it calls itself). You can get an idea of what recursion is about by standing between two mirrors. You see repeated versions of your reflection, each one smaller than the last. Recursion does that with problem solving. To solve a problem convert it to a similar but smaller version of the same problem (the first reflection). How do you solve that smaller problem? In the same way, as a smaller version of the same problem (the second reflection)… You keep solving those similar but smaller problems in the same way until eventually the problem is small enough to be trivial and so solved. For example, you can program a factorial method (multiplying all numbers from 1 to n together),in this way. You write that to compute factorial of a number, n, it just calls itself and computes the factorial of (n-1). It just multiply that result by n to get the answer. In addition you just need a trivial case eg that factorial of 1 is just 1.

factorial (1) = 1

factorial (n) = n * factorial (n-1)

Peter was an enthusiastic and inspirational teacher and taught ALGOL to others. This included teaching one of the other, then young but soon to be great, pioneers of Programming Theory, Tony Hoare. Learning about recursion led Hoare to work out a way, using recursion, to finally explain the idea that made his name in a simple and elegant way: the fast sorting algorithm he invented called Quicksort. The ideas included in ALGOL had started to prove their worth.

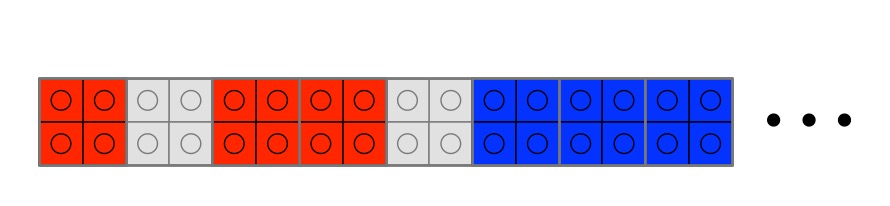

The idea of including recursion in a programming language was part of the foundation for the idea of functional programming languages. They are mathematically pure languages that use recursion as the way to repeat instructions. The mathematical purity makes them much easier to understand and so write correct programs in. Peter ran with the idea of programming in this way. He showed the power that could be derived from the fact that it was closely linked to a kind of logic called the Lambda Calculus, invented by Alonso Church. The Lambda Calculus is a logic built around mathematical functions. One way to think about it is that it is a very simple and pure way to describe in logic what it means to be a mathematical function – as something that takes arguments and does computation on them to give results. This Church showed was a way to define all possible computation just as Turing’s Turing machine is. It provides a simple way to express anything that can be computed.

Peter showed that the Lambda Calculus could be used as a way to define programming languages: to define their “semantics” (and so make the meaning of any program precise).

Having such a precise definition or “semantics” meant that once a program was written it would be sure to behave the same way whatever actual computer it ran on. This was a massive step forward. To make a new programming language useful you had to write compilers for it: translators that convert a program written in the language to a low level one that runs on a specific machine. Programming languages were generally defined by the compiler up till then and it was the compiler that determined what a program did. If you were writing a compiler for a new machine you had to make sure it matched what the original compiler did in all situations … which is very hard to do.

So having a formal semantics, a mathematical description of what a compiler should do, really makes a difference. It means anyone developing a new compiler for a different machines can ensure the compiler matches that semantics. Ultimately, all compilers behave the same way and so one program running on two different manufacturer’s machines are guaranteed to behave the same way in all situations too.

Peter went on to invent the programming language ISWIM to illustrate some of his ideas about the way to design and define a programming language. ISWIM stands for “If you See What I Mean”. A key contribution of ISWIM was that the meaning of the language was precisely defined in logic following his theoretical work. The joke of the name meant it was logic that showed what he meant, very precisely! ISWIM allowed for recursive functions, but also allowed recursion in the definition of data structures. For example, a List is built from a List with a new node on the end. A Tree is built from two trees forming the left and right branches of a new node. They are defined in terms of themselves so are recursive.

Building on his ideas around functional programming, Peter also invented something he called the SECD machine (named after its components: a Stack, Environment, Control and Dump). It effectively implements the Lambda calculus itself as though it is a programming language.ISWIM provided a very simple but useful general-purpose low level language. It opened up a much easier way to write compilers for functional programming languages for different machines. Just one program needed to be written that compiled the language into SECD. Then you had a much simpler job of writing a compiler to convert from the low level SECD language to the low level assembly language of each actual computer. Even better, once written, that low level SECD compiler could be used for different functional programming languages on a single machine. In SECD, Peter also solved a flaw in ALGOL that prevented functions being fully treated as data. Functions as Data is a powerful feature of the best modern programming languages. It was the SECD design that first provided a solution. It provided a mechanism that allowed languages to pass functions as arguments and return them as results just as you could do with any other kind of data without problem.

In the later part of his life Peter focussed much more on his work supporting the LGBTQ+ community having decided that Computer Science was not doing the good for humanity he once hoped. Instead, he thought it was just supporting companies making profit, ahead of the welfare of people. He decided that he could do more good as part of the LGBTQ+ community. Since his death there has been an acceleration in the massing of wealth by technology companies, whereas support for diversity has made a massive difference for good, so in that he was prescient. His contributions have certainly, though, provided a foundation for better software, that has changed the way we live in many ways for the better. Because of his work they are less likely to cause harm because of programming mistakes, for example, so in that at least he has done a great deal of good.

by Paul Curzon, Queen Mary University of London

More on …

- The logic behind syntactic sugar (more of the work of Peter Landin)

- LGBTQ+ Computer Science Greats

- Theory, Logic and Deduction

- Peter Landin’s Obituary [EXTERNAL]

Magazines …

Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish a new post to the CS4FN blog.

EPSRC supports this blog through research grant EP/W033615/1.