Computer Scientists are working to support traditional music from around the world.

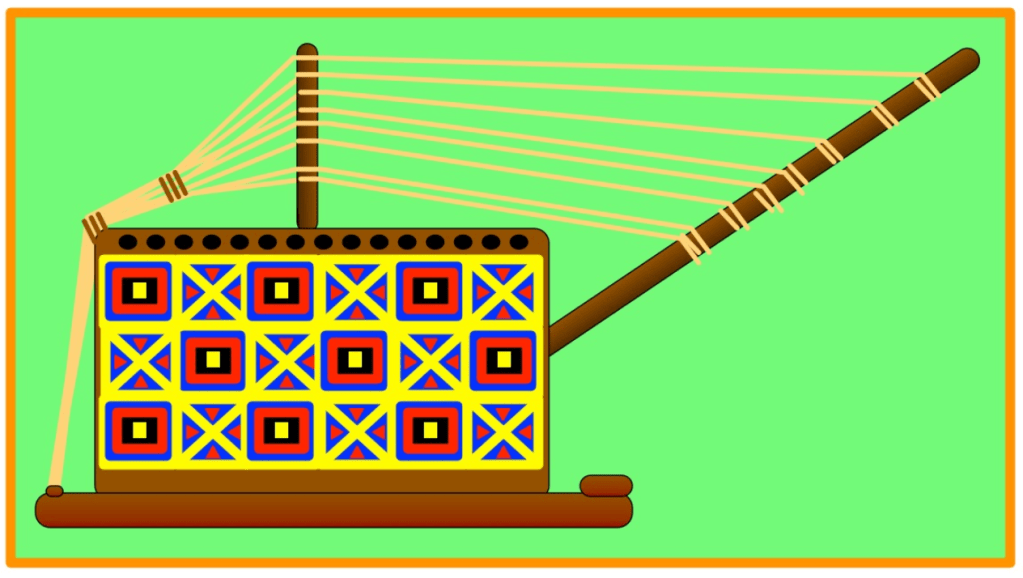

A seperewa is a traditional “harp-lute” musical instrument of the Akan people in Ghana, Africa. It has strings that are plucked a bit like a guitar. It is dying out because of the rise of western music. Researchers are now testing AIs that were trained on western music to see if they still work with such different seperewa music. They are also trying to understand exactly how this traditional music is different.

Protecting traditional instruments

Colonisers introduced European guitars to Ghana in the late 1800s and their sound began to influence and even replace seperewa music. Worried by this, in the mid-1900s people made recordings to preserve endangered seperewa music and to remind people what it sounds like. Ghanaian musicians are now reviving the seperewa, so we might continue to hear more of its lovely sound in future.

AI to the rescue

A team of computer scientists and music experts have investigated recordings of seperewa music to see how well western AI tools can analyse that style of music, given it is tuned in a completely different way, so plays different notes to a western instrument.

First the team used one AI tool to separate the sounds of the seperewa from the singing. It struggled a bit and left some of the singing in the seperewa track and vice versa but overall did a good job,

They then used a different AI to analyse the sounds of the seperewa. The found that the seperewa music had its own, unique musical fingerprint, revealing a rich tapestry of sound that was clearly different from western music.

The research is helping to preserve a vital part of Ghanaian culture. It has shown in detail how their music is different to anything western and so that something unique and precious would be lost if it died out.

Jo Brodie and Paul Curzon, Queen Mary University of London

Watch …

Hear what a seperewa / seprewa sounds like at this YouTube video: The seprewa – the original African guitar [EXTERNAL]

More on…

We have LOTS of articles about music, audio and computer science. Have a look in these themed portals for more:

- Music and AI

- Music, Digital or Not

- Audio Engineering

- Read more about Music and AI in our mini-magazine “A Bit of CS4FN” issue 6 [COMING SOON]

Getting technical…

- Analyzing Pitch Content in Traditional Ghanaian Seperewa Songs (2024) by Kelvin L Walls, Iran R Roman, Kelsey Van Ert, Colter Harper and Leila Adu-Gilmore (PDF) [EXTERNAL]

Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish a new post to the CS4FN blog.