When disasters involving technology occur, human error is often given as the reason, but even experts make mistakes using poor technology. Rather than blame the person, human error should be seen as a design failure. Bad design can make mistakes more likely and good design can often eliminate them. Optical illusions and magic tricks show how we can design things that cause everyone to make the same systematic mistake, and we need to use the same understanding of the brain when designing software and hardware. This is especially important if the gadgets are medical devices where mistakes can have terrible consequences. The best computer scientists and programmers don’t just understand technology, they understand people too, and especially our brain’s fallibilities. If they don’t, then mistakes using their software and gadgets are more likely. If people make mistakes, don’t blame the person, fix the design and save lives.

Illusions

Optical illusions and magic tricks give a mirror on the limits of our brains. Even when you know an optical illusion is an illusion you cannot stop seeing the effect. For example, this image of an eye is completely flat and stationary: nothing is moving. And yet if you move your head very slightly from side to side the centre pops out and seems to be moving separately to the rest of the eye.

Illusions occur because our brains have limited resources and take short cuts in processing the vast amount of information that our senses deliver. These short cuts allow us to understand what we see faster and do so with less resources. Illusions happen when the short cuts are applied in a way where they do not apply.

What this means is that we do not see the world as it really is but see a simplified version constructed by our subconscious brain and provided to our conscious brain. It is very much like in the film, the Matrix, except it is our own brains providing the fake version of the world we experience rather than alien computers.

Attention

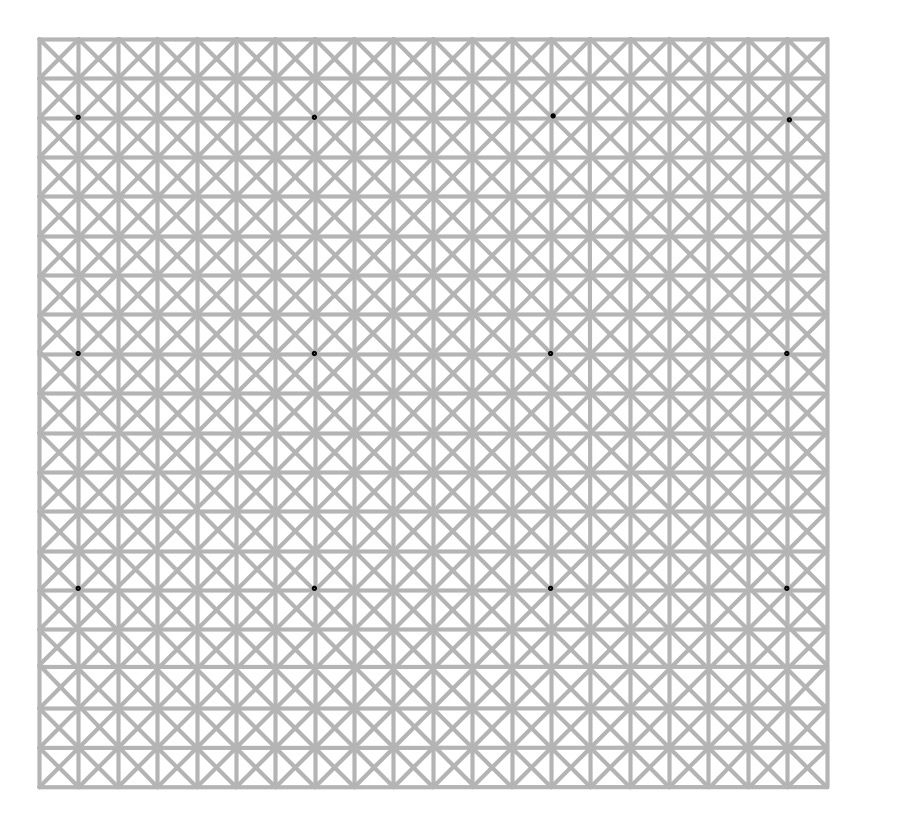

The way we focus our attention is one example of this. You may think that you see the world as it is, but you only directly see the things you focus on, your brain fills out the rest rather than constantly feeding the actual information to you constantly. It does this based on what it last saw there but also on the basis of just completing patterns. The following illusion shows this in action. There are 12 black dots and as you move your attention from one to the next you can see and count them all. However, you cannot see them all at once. The ones in your peripheral vision disappear as you look away as the powerful pattern of grey lines takes over. You are not seeing everything that is there to be seen!

Find more on the links to magic in our book

Our brains also have very limited working memory and limited attention. Magicians also exploit this to design “magical systems” where a whole audience make the same mistake at the same time. Design the magic well so that these limitations are triggered and people miss things that are there to be seen, forget things they knew a few moments before, and so on. For example, by distracting their attention they make them miss something that was there to be seen.

What does this mean to computer scientists?

When we design the way we interact with a computer system, whether software and hardware, it is also possible to trigger the same limitations a magician or optical illusion does. A good interaction designer therefore does the opposite to a magician and, for example: draws a user’s attention to things that must not be missed at a critical time; they ensure they do not forget things that are important, they help them keep track of the state of the system, they give good feedback so they know what has happened.

Most software is poorly designed leading to people making mistakes, not all the time, but some of the time. The best designs will help people avoid making mistakes and also help them spot and fix mistakes as soon as they do make them.

Examples of poor medical device design

The following are examples of the interfaces of actual medical devices found in a day of exploration by one researcher (Paolo Masci) at a single very good hospital (in the US).

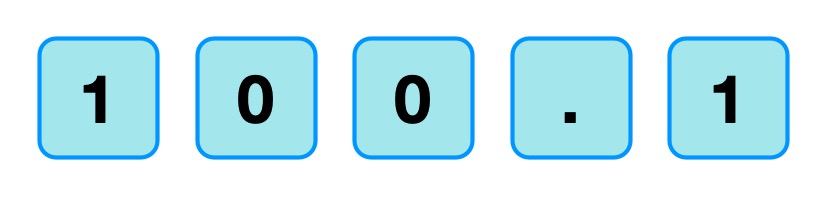

When the nurse or doctor types the following key sequence as a drug dose rate:

one infusion pump, without any explicit warning, other than the number being displayed, registered the number entered as 1001.

Probably, the programmer had been told that when doses are as large as 100, then fractional doses are so relatively small that they make no difference. A user typing in such fractional amounts, is likely making an error as such a dose is unlikely to be prescribed. The typing of the decimal point is therefore just ignored as a mistake by the infusion pump. Separately, (perhaps coded by a different programmer in the team, or at a different time) until the ENTER key is pressed the code treats the number as incomplete. Any further digits typed are therefore just accepted as part of the number.

A different design by a different manufacturer also treats the key sequence as 1001 (though in the case shown 1001 is rejected as it exceeds the maximum allowable rate, caused by the same issue of the device silently ignoring a decimal point).

This suggests two different coding teams indipendently coded in the same design flaw that led to the same user error.

What is wrong with that?

Devices should never silently ignore and/or correct input if bad mistakes are to be avoided. Here, that original design flaw, could lead to a dose 10x too big being infused into a patient and that could kill. It relies on the person typing the number noticing that the decimal point has been ignored (with no help from the device). Decimal points are small and easily missed of course. Also, their attention cannot be guaranteed to be on the machine and, in fact, with a digit keypad for entering numbers that attnetion is likely to be on the keys. Alarms or other distractions elsewhere could easily mean they do not notice the missing decimal point (which is a tiny thing to see).

An everyday example of the same kind of problem, showing how easily mistakes are missed is in auto-completion / auto-correction of spelling mistakes in texts and word processors. Goofs where an auto-corrected word are missed are very common. Anything that common needs to be designed away in a safety critical system.

Design Rules

One of the ways that such problems can be avoided is by programmers following interaction design rules. The machine (and the programmer writing the code) does not know what a user is trying to input when they make a mistake. One design rule is therefore that a program should therefore NEVER correct any user error silently. Here perhaps the mistake was pressing 0 twice rather than pressing the decimal point. In the case of user errors, the program should raise awareness of the error, and not allow further input until the error is corrected. The program should explicitly draw the person’s attention to the problem (eg changing colour, flashing, beeping, etc). This involves using the same understanding of cognitive psychology as a magician, to control their attention. Whereas a magician would be taking their attention away from the thing that matters, the programmer draws theur attention to it.

It should make clear in an easily understandable error message what the problem is (eg here “Doses over 99 should not include decimal fractions. Please delete the decimal point.”) It should then leave the user to make the correction (eg deleting the decimal point) not do it itself.

By following a design rule such as this programmers can avoid user errors, which are bound to happen, from causing a big problem.

Avoiding errors

Sometimes the way we design software interfaces and their interaction design we can do even better than this, though. We are letting people make mistakes and then telling them to help them pick up the pieces afterward. Sometimes we can do better than this and with better design help them avoid making the mistake in the first place or spot the mistake themselves as soon as they make it.

Doing this is again about controlling user attention as a magician does. An interaction designer needs to do this again in the opposite wayto the magician though, directing the users attention to the place it needs to be to see what is really happening as they take actions rather than away from it.

To use a digit keypad, the users attention has to be on their fingers so they can see where to put their fingers to press a given digit. They look at the keypad, not the screen. The design of the digit keypad draws their attention to the wrong place. However, there are lots of ways to enter numbers and the digit keypad is only one. One other way is to use cursor keys (left, right, up and down) and have a cursor on the screen move to the position where a digit will be changed. Now, once the person’s finger is on say the up arrow, attention naturally moves to the screen as that button is just pressed repeatedly until the correct digit is reached. The user is watching what is happening, watching the program’s output, rather than their input, so is now less likely to make a mistake. If they do overshoot, their attention is in the right place to see it and immediately correct it. Experiments showed that this design did lead to fewer large errors though is slower. With numbers though accuracy is more likely to matter than absolute speed, especially in medical situations.

There are still subtleties to the design though – should a digit roll over from 9 back to 0, for example? If it does should the next digit increase by 1 automatically? Probably not, as these are the things that lead to other errors (out by a factor of 10). Instead going up from 9 should lead to a warning.

Learn from magicians

Magicians are expert at making people make mistakes without them even realising they have. The delight in magic comes from being so easily fooled so that the impossible seems to have happened. When writing software we need to using the same understanding of our cognitive resources and how to manipulate them to prevent our users making mistakes. There are many ways to do this, but we should certainly never write software that silently corrects user errors. We should control the users attention from the outset using similar techniques to a magician so that their attention is in the right place to avoid problems. Ideally a number entry system such as using cursor keys to enter the number rather than a digit keypad should be used as then the attention of the user is more likely to be on the number entered in the first place.

– Paul Curzon, Queen Mary University of London

More on …

- Screaming headline kills

- Dragonfly AI: I see what you see

- Magic and design: The teleporting robot

- Much Ado about Nothing

Related Careers

Careers related to this article include:

- Interaction designer

- Responsible for the design of not just the interface but how a device or software is used. Applying creativity and applying existing design rules to come up with solutions. Has a deep understanding both of technical issues and of the limitations of human cognition (how our brains work).

- Usability consultant

- Give advice on making software and gadgets generally easier to use, evaluate designs for features that will make them hard to use or increase the likelihood of errors, finding problems at an early stage.

- User experience (UX) consultant

- Give advice on ensuring users of software have a good positive experience and that using it is not for example, frustrating.

- Medical device developer

- Develop software or hardware for medical devices used in hospitals or increasingly in the home by patients. Could be improvements to existing devices or completely novel devices based on medical or biomedical breakthroughs, or on computer science breakthroughs, such as in artificial intelligence.

- Research and Development Scientist

- Do experiments to learn more about the way our brains work, and/or apply it to give computers and robots a way to see the world like we do. Use it to develop and improve products for a spin-off company.

Magazines …

Our Books …

- The Power of Computational Thinking:

- Games Magic and Puzzles to help you become a computational thinker

- Conjuring with Computation

- Learn the basics of computer science through magic tricks

Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish a new post to the CS4FN blog.

This blog is funded by EPSRC on research agreement EP/W033615/1.