Magic tricks are just algorithms – they involve a magician following the steps of the trick precisely. But how can a magician be sure a trick will definitely work when they do it in front of an audience? Just like computer scientists who can prove their algorithms always work, a magician can use logic and deduction to be sure their tricks always work too.

Try the following trick on your own first, before reading about how it works or trying it with a volunteer. Take the role of both the magician and volunteer. I will do my best to remote-control the magic via my own mind-meld with you as you read my words, to try and make sure it works for you!

The magical effect

Take a full pack of playing cards and give them a good shuffle. Fan the cards face down. Now ask a volunteer to think of the colour RED and point to a card. Cut the pack at that point and count the top eight cards into a pile face down. Now ask them to think BLACK and touch another card. Cut the pack there and count out 7 cards onto the pile. Repeat this with 6 cards and then 5 cards having them think RED and then BLACK. Have the volunteer shuffle the selected cards then turn the pile face up.

You take the cards that are left and shuffle them, keeping them face down. Have the volunteer now run through their cards taking out groups of cards that are together and of the same colour. They should put them either in a “RED” pile in front of them if they are a group of red cards, or in a “BLACK” pile if they are black, telling you how many cards they have placed in that pile. As they take each group of cards, you, focussing hard on your cards, but without looking at what they are, pick out the same number of cards from points through the pack as the volunteer put down, and put them in your own corresponding “RED” or “BLACK” pile in front of you, Place your cards face down. In this way, they end up with a pile of red cards and a pile of black cards, both face up in front of them. You end up with two corresponding face down piles in front of you. They have seen their cards but yours contain cards that you have not seen. Once they have run out of cards and you have placed your matching cards, stop and think for a moment, then go through your two piles and swap two cards without looking at them, saying you believe you made a couple of mistakes and those two ended up in the wrong piles.

Now, looking happy, tell the volunteer that through a mind-meld between you, them and the red and black cards you have, you believe, succeeded in your aim. Remind them that the piles were shuffled, they were responsible for the way the cards were split which was at random, and you haven’t seen any of your cards. One card out at any point and the trick would not have worked. Despite this, announce that you have managed to place the same number of red cards in your red pile as you have placed black cards in your black pile. Pass them the two piles in turn and ask them to check by first counting the red cards in your face down “RED” pile onto the table, and then do the same with the black cards that are in your “BLACK” pile.

Amazingly you have succeeded, the number of red cards in the red pile is the same as the number of black cards in the black pile.

Proving it always works

Did I mind meld with you to make it work? Or is something else going on? We can actually use logic and deduction (with some algebra) to show it works.

First we need to make a mathematical model of the situation – essentially describe the situation, or at least the parts of it that matter, in maths. That sounds a bit scary but it isn’t really. Its just giving names to some piles of cards! Let’s go through it…

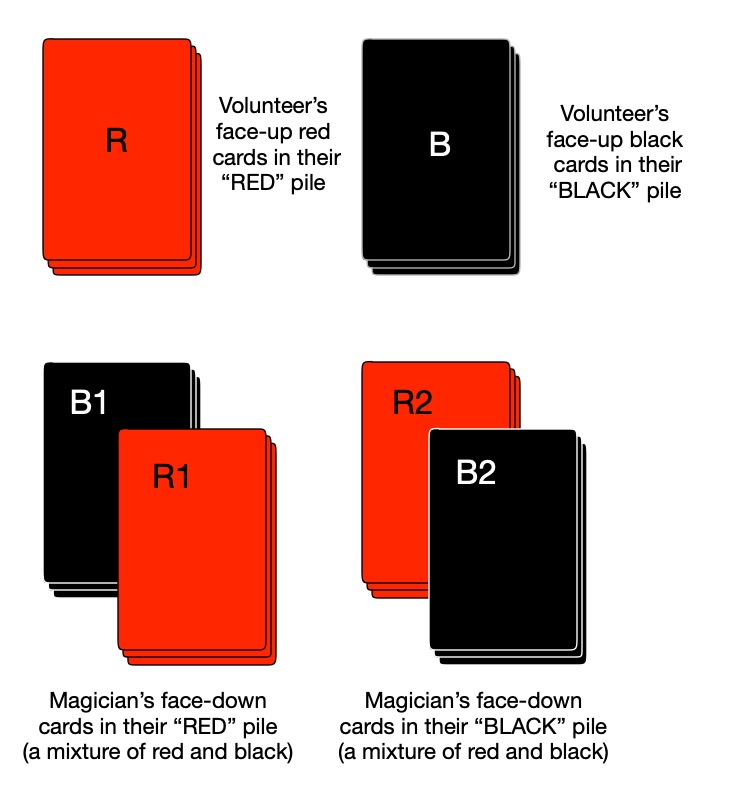

In the trick, we end up with four piles of cards. A RED pile and a BLACK pile, both face up, in front of the volunteer and a RED pile and a BLACK pile, both face down, in front of the magician (see the picture above). We do not know how many cards are in each pile and it will be different each time we do the trick anyway because of all the shuffling. Luckily the actual numbers don’t matter. In the trick we care about the numbers of red cards and the numbers of black cards, Let us therefore use mathematical variables to represent these different numbers (that just means give them names!). Mathematicians often use names like x and y for variables, but to help us remember what they stand for we will use variations on R and B to mean numbers of red and black cards respectively.

So, we will use R to stand for the number of red cards in the volunteer’s face up “RED” pile (which are all red) and B to mean the number of black cards in the volunteers face up “BLACK” pile (which are all black).

Now for the magician’s face down piles. They have both red and black cards in each pile so we will write R1 to mean the number of red cards in the magician’s face down “RED” pile and B1 to mean the number of black cards in the magician’s face down “RED” pile. Similarly, we will write R2 to mean the number of red cards in the magician’s face down “BLACK” pile and B2 to mean the number of black cards in the magician’s face down “BLACK” pile. We have the situation as shown below in the picture..

In doing this we are doing a form of abstraction – hiding of detail – we have hidden the actual numbers of red and black cards in each pile within our description, describing them with variables as the precise numbers do not matter (and are different every time we do the trick anyway).

So far so good. Now, we want to try and prove that the trick always works. But how to start? First, just think of any facts you know about the situation (and especially anything you know about red and black cards). It may not be obvious how it can help, but write it down anyway!

Well the first thing we know is that a full pack of cards was used, and there are 52 cards in a pack, half (26) red and half (26) black. All these cards ended up on the table in one pile or another. So that means if we add up all the red cards in the four piles it will equal 26. How can we write this in terms of our variables? It is just:

R + R1 + R2 = 26

We add the three variables that stand for numbers of red cards and it equals 26. There are only three things to add for the four piles as one pile is all black. We can say a similar thing about the black cards:

B + B1 + B2 = 26

Now we have two different sums that equal the same thing (26) so we can put them together as equalling each other to get a combined equation which we will call EQUATION 1.

R + R1 + R2 = B + B1 + B2 (EQUATION 1)

That doesn’t seem to tell us much useful, but don’t worry, we are just gathering facts for now. What else do we know about how the trick worked? Well, every time the volunteer put some number of cards in their “RED” pile, the magician puts the same number of cards in their “RED” pile (though those cards may be red or black). That means that, throughout the two “RED” piles hold the same number of cards. The number of cards in one “RED” pile is R and the number of cards in the other “RED” pile is R1 + B1 (the reds plus the blacks in that pile). We can write this out as an equation:

R = R1 + B1

Now, this tells us that R is exactly the same as R1 + B1 so anywhere we see R we can replace it with R1 + B1. In particular, we can make this switch in EQUATION 1 to give:

(R1 + B1) + R1 + R2 = B + B1 + B2 (EQUATION 2)

With the same logical reasoning, we can deduce an equation for the “BLACK” piles too. The number of cards in one “BLACK” pile is B and the number of cards in the other “BLACK” pile is R2 + B2 (the reds plus the blacks in that pile). We can write this out as an equation:

B = R2 + B2

Substituting R2 + B2 for B into EQUATION 2 we get EQUATION 3

(R1 + B1) + R1 + R2 = (R2 + B2) + B1 + B2 (EQUATION 3)

Now, this seems to have just made things more complicated and not got us anywhere much, but we can now simplify it. Notice that there are two R1s on one side and two B2s on the other, each added, so we can group them together to get:

2R1 + B1 + R2 = R2 + 2B2 + B1

Also, on each side there is a B1 and that pair can cancel out (just subtract B1 from both sides and the equality holds but it is simpler), and on each side there is an R2 which can cancel in the same way. This leaves us with:

2R1 = 2B2

Of course the multiplication by 2 on both sides cancels too (just divide both sides by 2 and they will still be equal). We get:

R1 = B2

That is a very simple equation. It basically tells us that if you follow the steps of this trick that, whatever numbers of reds and blacks end up in each pile, R1 is guaranteed at the end to be the same number as B2. So what does that mean back in the real world? R1 just stands for the number of red cards in the magician’s “RED” pile. B2 just stands for the number of black cards in the magician’s “BLACK” pile. The equation we are left with just tells us that as long as we follow the steps (actually as long as we make the number of cards in each pair of piles match) then at the end the number of red cards in the magician’s “RED” pile will be the same as the number of black cards in the magician’s “BLACK” pile…and that is the “magical” result we predicted!

The trick will always work if you follow the steps!

Proving software and hardware always works

A magic trick involves the magician following steps precisely – following an algorithm. That is all computer hardware and software do – they follow algorithms to achieve some desired result (a magical effect). Just as we proved the trick always works, we can prove that other algorithms (whether implemented as a program or hardware) work using logical deduction too. That is one of the reasons why logic and deduction are so important to computer scientists. You do not want a trick to go wrong in front of an audience, so it is worth proving it always works. How much more important is it that all that software we now rely on for everyday life is error free. And what about a medical device keeping someone alive, or the software flying a plane. We want to be sure they always work. If they contain mistakes, people die. Logic and proof can therefore save lives, not just magic shows.

by Paul Curzon, Queen Mary University of London

More on …

Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish a new post to the CS4FN blog.

EPSRC supports this blog through research grant EP/W033615/1.