A puzzle about secrets

Ayo wants to send her friends Guang and Elham who live together secret messages that only the person she sends the message to can read. She doesnt want Guang to read the messages to Elham and vice versa.

Guang buys them all small lockable notebooks for Christmas. They are normal notebooks except that they have a lock that can be locked shut using a small in-built padlock. Each padlock can be opened with a different single key. Guang suggests that they write messages in their notebook and post it and the key separately to the person who they wish to send the message to. After reading the message that person tears that page out and destroys it, then returns the notebook and key. They try this and it appears to be working, apparently preventing the others from reading the messages that aren’t for them. They exchange lots of secrets…until one day Guang gets a letter from Ayo that includes a note with an extra message added on the end by Elham in the locked notebook. It says “I can read your messages. I know all your secrets – Elham”. She has been reading Ayo’s messages to Guang all along and now knows all their secrets. She now wants them to know how clever she has been.

How did she do it? (And what does it have to do with the beheading of Mary Queen of Scots?)

Breaking the system

Elham has, of course, been getting to the post first, steaming open the envelopes, getting the key and notebook, reading the message (and for the last one adding her own note). She then seals them back in the envelopes and leaves them for Guang.

A similar thing happened to betray Mary Queen of Scots to her cousin Queen Elizabeth I. It led to Mary being beheaded.

Is there a better way?

Ayo suggests a solution that still uses the notebooks and keys, but in which no keys are posted anywhere. To prove her method works, she sends a secret message to Guang, that Elham fails to read. How does she do it? See if you can work it out before reading on…and what is the link to computer science?

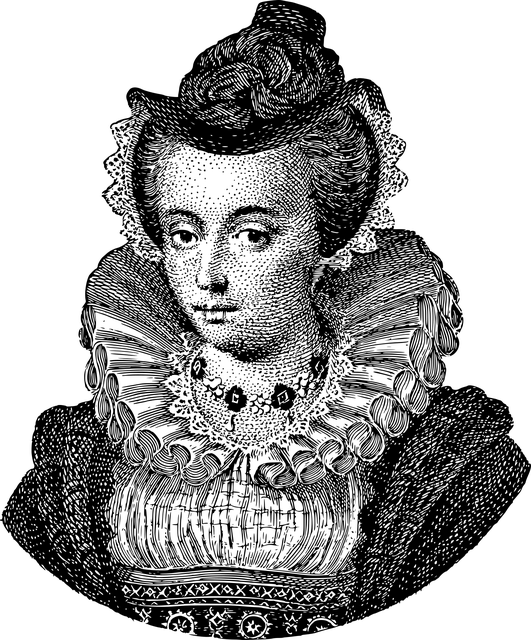

Mary Queen of Scots

The girls face a similar problem to that faced by Mary Queen of Scots and countless spies and businesses with secrets to exchange before and since…how to stop people intercepting and reading your messages. Mary was beheaded because she wasn’t good enough at it. The girls in the puzzle discovered, just like Mary, that weak encryption is worse than no encryption as it gives false confidence that messages are secret.

There are two ways to make messages secret – hide them so no one realises there is a message to read or disguise the message so only people in the know, are aware it exists (or both). Hiding the message is called Steganography. Disguising a message so it cannot be read even if known about is called encryption. Mary Queen of Scots did both and ultimately lost her life because her encryption was easy to crack, when she believed the encryption would protect her, it had given her the confidence to write things she otherwise would not have written.

House arrest

Mary had been locked up – under house arrest – for 18 years by Queen Elizabeth I, despite being captured only because she came to England asking her cousin Elizabeth to give her refuge after losing her Scottish crown. Elizabeth was worried that Mary and her allies would try to overthrow her and claim the English crown if given the chance. Better to lock her up before she even thought of treason? Towards the end of her imprisonment, in 1586 some of Mary’s supporters were in fact plotting to free her and assassinate Elizabeth. Unfortunately, they had no way of contacting Mary as letters were allowed neither in nor out by her jailors. Then, a stroke of good fortune arose. A young priest called Gilbert Gifford turned up claiming he had worked out a way to smuggle messages to and from Mary. He wrapped the messages in a leather package and hid them in the hollow bungs of barrels of beer. The beer was delivered by the brewer to Chartley Hall where Mary was held and the packages retrieved by one of Mary’s servants. This, a form of steganography, was really successful allowing Mary to exchange a long series of letters with her supporters. Eventually the plotters decided they needed to get Mary’s agreement to the full plot. The leader of the coup, Anthony Babington, wrote a letter to Mary outlining all the details. To be absolutely safe he also encrypted the message using a cipher that Mary could read (decipher). He soon received a reply in Mary’s hand also encrypted that agreed to the plot but also asked for the names of all the others involved. Babington responded with all the names. Unfortunately, unknown to Babington and Mary the spies of Elizabeth were reading everything they wrote – and the request for names was not even from Mary.

Spies and a Beheading

Unfortunately for Mary and Babington all their messages were being read by Sir Francis Walsingham, the ruthless Principal Secretary to Elizabeth and one of the most successful Spymasters ever. Gifford was his double agent – the method of exchanging messages had been Walsingham’s idea all along. Each time he had a message to deliver, Gifford took it to Walsingham first, whose team of spies carefully opened the seal, copied the contents, redid the seal and sent it on its way. The encrypted messages were a little more of a problem, but Walsingham’s codebreaker could break the cipher. The approach, called frequency analysis, that works for simple ciphers, involves using the frequency of letters in a message to guess which is which. For example, the most common letter in English is E, so the most common letter in an encrypted message is likely to be E. It is actually the way people nowadays solve crossword like code-puzzles know as Cross References that can be found in puzzle books and puzzle columns of newspapers.

When they read Babington’s letter they had the evidence to hang him, but let the letter continue on its way as when Mary replied, they finally had the excuse to try her too. Up to that point (for the 18 years of her house arrest) Elizabeth had not had strong enough evidence to convict Mary – just worries. Walsingham wanted more though, so he forged the note asking for the names of other plotters and added it to the end of one of Mary’s letters, encrypted in the same code. Babington fell for it, and all the plotters were arrested. Mary was tried and convicted. She was beheaded on February 8th 1587.

Private keys…public keys

What is Ayo’s method to get round their problems of messages being intercepted and read? Their main weakness was that they had to send the key as well as the locked message – if the key was intercepted then the lock was worthless. The alternative way that involves not sending keys anywhere is the following…

Suppose Ayo wants to send a message to Guang. She first asks Guang to post her notebook (without the key but left open) to her. Ayo writes her message in Guang’s book then snaps it locked shut and posts it back. Guang has kept the key safe all along. She uses it to open the notebook secure in the knowledge that the key has never left her possession. This is essentially the same as a method known by computer scientist’s as public key encryption – the method used on the internet for secure message exchange, including banking, that allows the Internet to be secure. In this scheme, keys come in 2 halves a “private key” and a “public key”. Each person has a secret “private key” of their own that they use to read all messages sent to them. They also have a “public key” that is the equivalent to Guang’s open padlock.

If someone wants to send me a message, they first get my public key – which anyone who asks for can have as it is not used to decrypt messages, just for other people to to encrypt them (close the padlock) before sending them to me. It is of no use to decrypt any message (reopen the padlock). Only the person with the private key (the key to the padlock) can get at the message. So messages can be exchanged without the important decryption key going anywhere. It remains safe from interception.

Saving Mary

Would this have helped Mary? No. Her problem was not in exchanging keys but that she used a method of encryption that was easy to crack – in effect the lock itself was not very strong and could easily be picked. Walsingham’s code breakers were better at decryption than Babington was at encryption.

by Paul Curzon, Queen Mary University of London, updated from the archive

More on …

Magazines …

Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish a new post to the CS4FN blog.

EPSRC supports this blog through research grant EP/W033615/1.