Today is the final post in our CS4FN Christmas Computing Advent Calendar – it’s been a lot of fun rummaging in the CS4FN back catalogue, and also finding out about some new things to write about.

Each day we’ve published a blog post about computing with the theme suggested by the picture on the advent calendar’s ‘door’. Our first picture was a woolly jumper so the accompanying post was about the links between knitting and coding, the door with a picture of a ‘pair of mittens’ on led to a post about pair programming and gestural gloves, a patterned bauble to an article about printed circuit boards, and so on. It was fun coming up with ideas and links and we hope it was fun to read too.

We hope you enjoyed the series of posts (click on any of the Christmas trees in this post to see them all) and that you are already having a very Merry Christmas.

And on to today’s post which is inspired by the picture of a Christmas Tree, so it’ll be a fairly botanically-themed post. The suggestion for this post came from Prof Ursula Martin of Oxford University, who told us about the ‘wood computer’.

The Wood Computer

by Jo Brodie, QMUL.

Other than asking someone “do you know what tree this is?” as you’re out enjoying a nice walk and coming across an unfamiliar tree, the way of working out what that tree is would usually involve some sort of key, with a set of questions that help you distinguish between the different possibilities. You can see an example of the sorts of features you might want to consider in the Woodland Trust’s page on “How to identify trees“.

Depending on the time of year you might consider its leaves – do they have stalks or not, do they sit opposite from each other on a twig or are they diagonally placed etc. You can work your way through leaf colour, shape, number of lobes on the leaf and also answer questions about the bark and other features of your tree. Eventually you narrow things down to a handful of possibilities.

What happens if the tree is cut up into timber and your job is to check if you’re buying the right wood for your project. If you’re not a botanist the job is a little harder and you’d need to consider things like the pattern of the grain, the hardness, the colour and any scent from the tree’s oils.

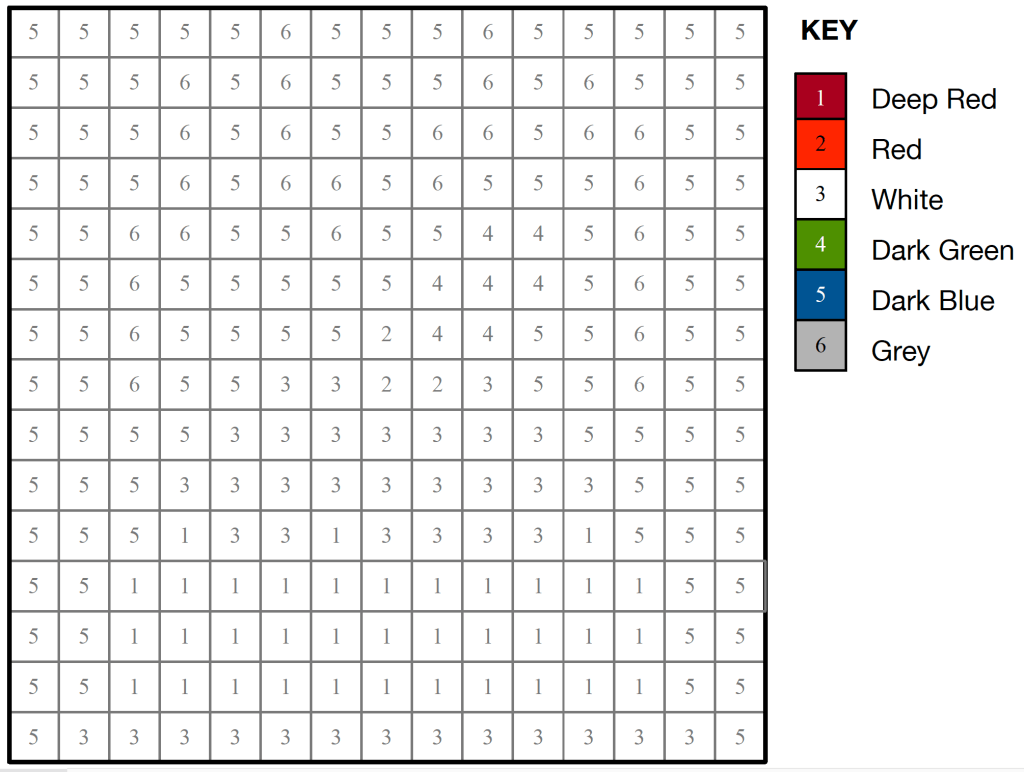

Historically, one way of working out which piece of timber was in front of you was to use a ‘wood computer’ or wood identification kit. This was prepared (programmed!) from a series of index cards with various wood features printed on all the cards – there might be over 60 different features.

Every card had the same set of features on it and a hole punched next to every feature. You can see an example of a ‘blank’ card below, which has a row of regularly placed holes around the edge. This one happens to be being used as a library card rather than a wood computer (though if we consider what books are made of…).

I bet you can imagine inserting a thin knitting needle into any of those holes and lifting that card up – in fact that’s exactly how you’d use the wood computer. In the tweet below you can see several cards that made up the wood computer.

One card was for one tree or type of wood and the programmer would add notch the hole next to features that particularly defined that type. For example you’d notch ‘has apples’ for the apple tree card but leave it as an intact hole on the pear tree card. If a particular type of timber had fine grained wood they’d add the notch to the hole next to “fine-grained”. The cards were known, not too surprisingly, as edge-notched cards.

You can see what one looks like here with some notches cut into it. You might have spotted how knitting needles can help you in telling different woods apart.

Holes and notches

Each card would end up with a slightly different pattern of notched holes, and you’d end up with lots of cards that are slightly different from each other.

How it works

Your wood computer is basically a stack of cards, all lined up and that knitting needle. You pick a feature that your tree or piece of wood has and put your needle through that hole, and lift. All of the cards that don’t have that feature notched will have an un-notched hole and will continue to hang from your knitting needle. All of the cards that contain wood that do have that feature have now been sorted from your pile of cards and are sitting on the table.

You can repeat the process several times to whittle (sorry!) your cards down by choosing a different feature to sort them on.

The advantage of the cards is that they are incredibly low tech, requiring no electricity or phone signal and they’re very easy to use without needing specialist botanical knowledge.

You can see a diagram of one on page 8 of the 20 page PDF “Indian Standard: Key for identification of commercial timbers”, from 1974.

The word ‘card’ features over 30 times on this page and the word Christmas over 10 times but this post isn’t actually about Christmas cards! We hope you had plenty of those 🙂 Merry Christmas.

Teachers: we have a classroom sorting activity that uses the same principles as the wood computer. Download our Punched Card Searching PDF from our activity page.

The creation of this post was funded by UKRI, through grant EP/K040251/2 held by Professor Ursula Martin, and forms part of a broader project on the development and impact of computing.

EPSRC supports this blog through research grant EP/W033615/1.