Ada (the language), is not the big player on the programming block these days. In 1997 the DoD1 cancelled their rule that you had to use Ada when working for them. Developers in commerce had always found Ada hard to work with and often preferred other languages. There are hundreds of other languages used in industry and by researchers. How many can you name?

Here are some fun clues about different languages. Can you work out their names?

(Answers at the end.)

- A big snake that will squash you dead.

- A famous Victorian woman who worked with Babbage.

- A, B, __

- A, B, __ (ouch)

- A precious, but misspelled, thing inside a shell.

- A tiny person chatting.

- A beautiful Indonesian island.

- A french mathematician and inventor famous for triangles.

(You can try an online version of our quiz here)

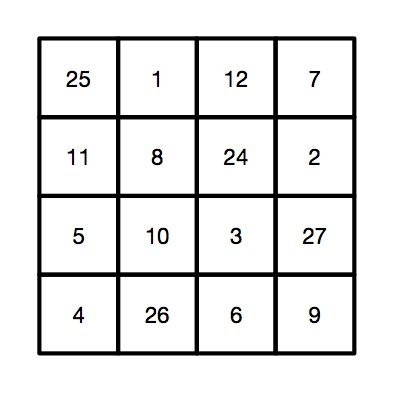

Today, the most popular programming languages are, well we don’t know, because it depends when you are reading this! Because what is fashionable, what is new is always changing. Plus it’s hard to agree what ‘the most popular’ means for languages (and pop stars!). Is it the most lines of code in use today? The favorite language of developers? The language everyone is learning? In July 2015 one particular website rated programing languages using features such as number of skilled software engineers who can use the language; number of courses to learn the language; search engine queries on the language and came up with the order.

- 1) Java

- 2) C

- 3) C++

- 4) C#

- 5) Python

Where is Ada? 30th out of 100s! The same website had shown Ada (the language) as 3rd top in 1985! What a fall from grace.

But have no fear, Ada still survives and lives on in millions of lines of avionics2, radar systems, space, shipboard, train, subway, nuclear reactors and DoD systems. Plus Ada is perhaps making a comeback. Ada 2012 is just being finalised, heralded by some as the next generation of engineering software with its emphasis on safety, security and reliability. So Ada meet Ada, it looks like you will be remembered and used for a long time still.

Github is a place where lots of programmers now develop and save their code. It encourages programmers to share their work. A kind of modern day, crowd sourced ‘mass of shared facts’ but coders would probably not say they did this just to ‘amuse their idle hours’. Popular coding tools on this platform are JavaScript. Java, Python, CSS, PHP, Ruby, C++. Ada doesn’t really feature, well not yet.

Jane Waite, Queen Mary University of London

- United States Department of Defense ↩︎

- Avionics (aviation electronics) includes all the electronics and software needed to fly aircraft safely. ↩︎

Related Magazine …

This article was originally published on page 19 of issue 20 of the CS4FN magazine. You can download a copy at the link below, and all of our previous magazine issues (free) here.

Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish a new post to the CS4FN blog.

Answers to the quiz…

Answers: 1) Python 2) Ada 3) C 4) C# (C sharp) 5) Perl 6) Smalltalk 7) Java 8) Pascal