Using wearable tech to monitor elite athletes’ health

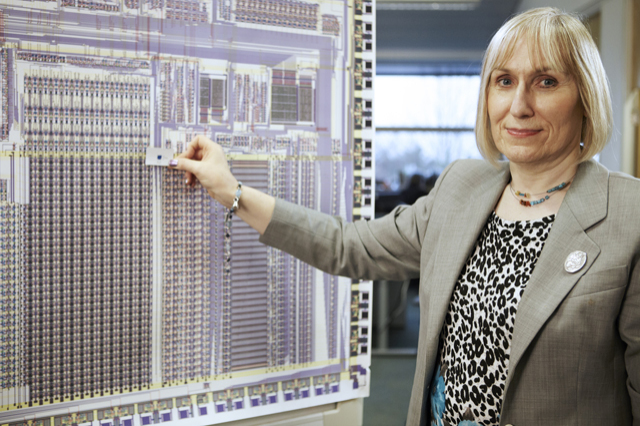

Microwaves aren’t just useful for cooking your dinner. Passing through your ears they might help check your health in future, especially if you are an elite athlete. Bioengineer Tina Chowdhury tells us about her multidisciplinary team’s work with the National Physics Laboratory (NPL).

Lots of wearable gadgets work out things about us by sensing our bodies. They can tell who you are just by tapping into your biometric data, like fingerprints, features of your face or the patterns in your eyes. They can even do some of this remotely without you even knowing you’ve been identified. Smart watches and fitness trackers tell you how fast you are running, how fit you are and whether you are healthy, how many calories you have burned and how well you are sleeping or not sleeping. They also work out things about your heart, like how well it beats. This is done using optical sensor technology, shining light at your skin and measuring how much is scattered by the blood flowing through it.

Microwave Sensors

With PhD student, Wesleigh Dawsmith, and electronic engineer, microwave and antennae specialist, Rob Donnan, we are working on a different kind of sensor to check the health of elite athletes. Instead of using visible light we use invisible microwaves, the kind of radiation that gives microwave ovens their name. The microwave-based wearables have the potential to provide real-time information about how our bodies are coping when under stress, such as when we are exercising, similar to health checks without having to go to hospital. The technology measures how much of the microwaves are absorbed through the ear lobe using a microwave antenna and wireless circuitry. How much of the microwaves are absorbed is linked to being dehydrated when we sweat and overheat during exercise. We can also use the microwave sensor to track important biomarkers like glucose, sodium, chloride and lactate which can be a sign of dehydration and give warnings of illnesses like diabetes. The sensor sounds an alarm telling the person that they need medication, or are getting dehydrated, so need to drink some water. How much of the microwaves are absorbed is linked to being dehydrated

Making it work

We are working with with Richard Dudley at the NPL to turn these ideas into a wearable, microwave-based dehydration tracker. The company has spent eight years working on HydraSenseNPL a device that clips onto the ear lobe, measuring microwaves with a flexible antenna earphone.

A big question is whether the ear device will become practical to actually wear while doing exercise, for example keeping a good enough contact with the skin. Another is whether it can be made fashionable, perhaps being worn as jewellery. Another issue is that the system is designed for athletes, but most people are not professional athletes doing strenuous exercise. Will the technology work for people just living their normal day-to-day life too? In that everyday situation, sensing microwave dynamics in the ear lobe may not turn out to be as good as an all-in-one solution that tracks your biometrics for the entire day. The long term aim is to develop health wearables that bring together lots of different smart sensors, all packaged into a small space like a watch, that can help people in all situations, sending them real-time alerts about their health.

Tina Chowdhury, Institute of Bioengineering, School of Engineering and Materials Science, Queen Mary University of London

More on …

Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish a new post to the CS4FN blog.

This blog is funded by EPSRC on research agreement EP/W033615/1.