Where does a naked mole-rat wear its computing gadgetry? Under its skin….

Naked mole-rats are fascinating creatures. They are highly social, living in colonies. They spend their lives permanently underground in burrows, and that’s why they have no fur just whiskers. They don’t need it. Living underground means they are difficult to study. Normally researchers simply watch animals to study their behaviour, but that’s not possible for naked mole-rats.

Tag ’em

To allow them to be observed, one colony of 28 animals, called Colony Omega, went digital. They all have an implant under their skin. These tags are just smaller versions of ones used by vets to tag pets. Sensors around their burrow detect when the tags are close. This means the naked mole-rats can be watched in real-time as they move around the burrow. It’s allowing the biologists to study patterns in their behaviour such as how different animals take on different roles in the colony.

Interactive rat art

Julie Freeman, an artist and computer scientist at QMUL, used the same data in a different way. She leads a team creating interactive art based on the naked mole-rat data. ‘A Selfless Society‘, for example, is an abstract animation that changes as a result of the live data from the colony. The sculpture ‘This is Nature Now‘ also represents the live data from the colony but using soft robotic techniques (see page 13 of the magazine linked below). It moves based on the movements of the naked mole-rats. We often experience nature through technology, watching it on screens rather than in real-life. ‘This is Nature Now’ explores how physical, non-living objects can convey a sense of life.

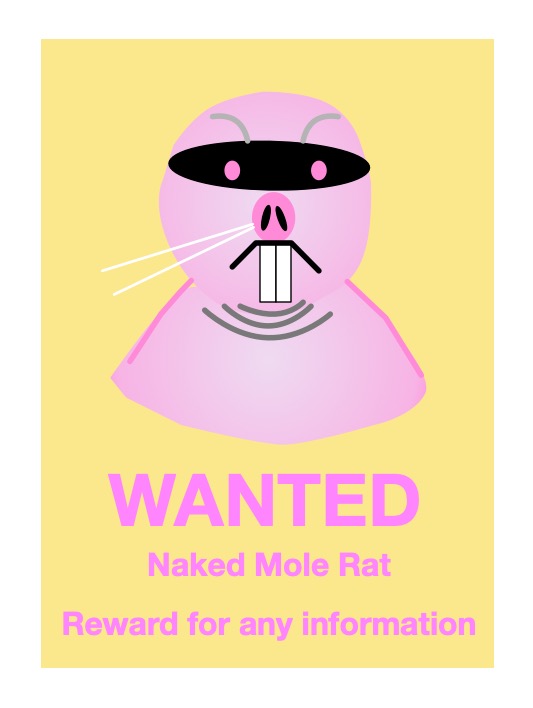

Private portraits

Colony Omega also has its own gallery of portrait photos, taken by Lorna Ellen Faulkes. The eyes of the naked mole-rats are blocked out (to protect their identity!) The idea is to make people think about data privacy. Technology raises big issues over our own privacy. We now give away vasts amount of personal information without realising. What about the data privacy of animals?

This may seem silly, but is a very real problem. Tourists posting images of endangered animals and plants on social media from safaris has caused problems. It has led poachers to the animals and plants photographed, putting them in serious danger. The problem arises because modern digital cameras log the place a photo is taken, and this ‘metadata’ is included with the photograph posted for anyone to see who knows where to look.

Paul Curzon, Queen Mary University of London

More on …

- Find out more about Colony Omega and see the art at rat.systems/colony/

This article was originally published on the CS4FN website and a copy can also be found on page 6 of Issue 25 of CS4FN, “Technology worn out (and about)“, on wearable computing, which can be downloaded as a PDF, along with all our other free material, here: https://cs4fndownloads.wordpress.com/

Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish a new post to the CS4FN blog.

This blog is funded by EPSRC on research agreement EP/W033615/1.