Next time you are in a large crowd, look around you: all those people moving together, and mostly not bumping into each other. How does it happen? Flocks of birds and schools of fish are also examples of this ‘swarm intelligence’. Computer Scientists have been inspired by this behaviour to come up with new solutions to really difficult problems.

Swarming behaviour requires the individuals (birds, fish or people) to have a set of rules about how to interact with the individuals nearest to them. These so-called ‘local’ rules are all that’s needed to give rise to the overall or ‘global’ behaviour of the swarm. We adjust our individual behaviour according to our current state but also the current state of those around us. If I want to turn left then I do it slowly so that others in the crowd can be aware of it and also start to turn. I know what I am doing and I know what they are doing. This is how information makes its way from the edges of the crowd to the centre and vice versa.

A swarm is born

The way a crowd or swarm interacts can be explained with simple maths. This maths is a way of approximating the complex psychological behaviour of all the individuals on the basis of local and global rules. Back in 1995 James Kennedy, a research psychologist, and Computer Scientist Russ Eberhart, having been inspired by the study of bird flocking behaviour by biologist Frank Heppner, realised that this swarm intelligence could be used to solve difficult computer problems. The result was a technique called Particle Swarm Optimisation (PSO).

Travel broadens the mind

An optimisation problem is one where you have a range of options to choose from and you want to know the best solution. One of the classic problems is called ‘The travelling salesperson’ problem. You work for a company and have to deliver packages to say 12 towns. You look at the map. There are many different routes to take, but which is the one that will let you visit all 12 towns using the least petrol? Here the choices are the order in which you visit the towns, and the constraint is that you want to do the least driving. You could have a guess, select the towns in a random order and work out how far you’d have to travel to visit them in this order. You then try another route through all 12 and see if it takes less mileage, and so on. Phew! It could take a long time to work out all the possible routes for 12 towns to see which was best. Now imagine your company grows and you have to deliver to 120 towns or 1200 towns. You would spend all your time with the maps trying to come up with the cheapest solutions. There must be a better way? Well actually simple as this problem seems it’s an example of a set of computational problems known as NP-Complete problems and it’s not easy to solve! You need some guidance to help you through and that’s where swarm optimisation come in. It’s an example of a so-called metaheuristic algorithm: a sort of ‘general rule of thumb’ to help solve these types of problem. It won’t always work unless you have infinite time but it’s better than just trying random solutions. So how does swarm optimisation work here?

State space: the final frontier

First we need to turn the problem into something called a state space. You probably use state spaces all the time but just don’t know it. Think about yourself. What are the characteristic you would use to tell people about your current state: age, height, weight and so on. You can identify yourself by a list of say 3 numbers – one for age, one for height, one for weight. It’s not everything about you of course but it does define your state to some extent. Your numbers will be different to other people’s numbers, if you take all the numbers for your friends you would have a state space. It would be a 3-dimensional space with axes: age, height and weight, and each person would be a point in that space at some coordinate (X, Y, Z).

So state spaces are just a way of representing the possible variations in some problem. With the 12 towns problem, however, you couldn’t draw this space: it would be 12 dimensional! It would have one axis for each town, with the position on the axis an indication of where in the route it was. Every point in that space would be a different route through the 12 towns, so each point in the space would have coordinates (x1, x2, x3, … x11, x12). For each point there would also be a mileage associated with the route, and the task is to find the coordinate point (route) with the lowest mileage.

Where no particle has swarmed before

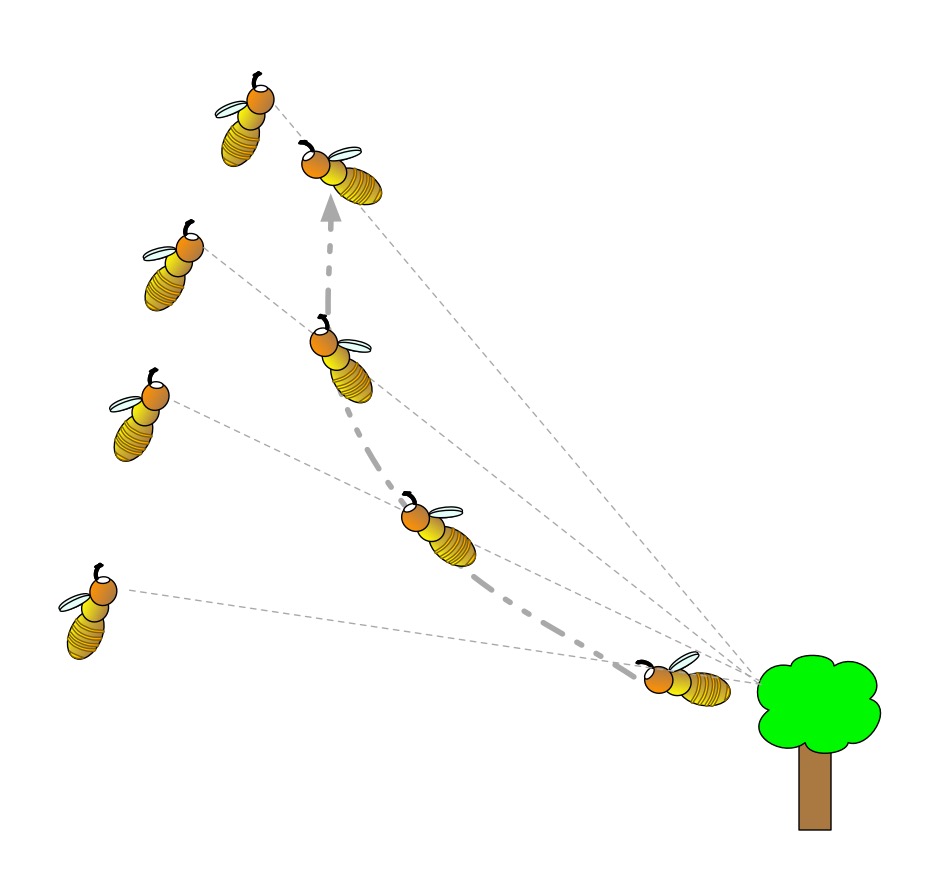

Enter swarm optimisation. We create a set of ‘particles’ that will be like birds or fish, and will fly and swarm through our state space. Each particle starts with a random starting location in the state space and calculates the mileages involved for the coordinates (route) they are at. The particles remember (store) this coordinate and also the value of the mileage at that position. Each particle therefore has it’s own known ‘local’ best value (where the lowest mileage was) but can compare this with other neighbouring particles to see if they have found any even better solutions. The particles then move onwards randomly in a direction that tends to move them towards their own local best and the best value found by their neighbours. The particles ‘fly’ around the state space in a swarm homing in on even better solutions until they all converge on the best they can find: the answer.

It may be that somewhere in a part of the space where no particle has been there is an even better solution, perhaps even the best solution possible. Our swarm will have missed it! That’s why this algorithm is a heuristic, a best guess to a tough problem. We can always add some more particles at the start to fill more of the state space and reduce the chance of missing a good solution, but we cant ever be 100% sure.

Swarm optimisation has been applied to a whole range of tough problems in computing, electronic engineering, medicinal chemistry and economics. All it needs is for you to create an appropriate state space for your problem and let the particles fly and swarm to a good solution.

It’s yet another example of clever computing based on behaviours found in the natural world. So next time you’re in a crowd, look around and appreciate all that collective interacting swarm intelligence…but make sure you remember to watch where you are stepping.

by Peter W. McOwan, Queen Mary University of London. From the archive.

More on …

Related Magazines …

- Issue 4 – Computer Science and Biolife

- Biology loves technology

- Issue 3 – Computer Science and entertainment

Our Books …

- The Power of Computational Thinking:

- Games Magic and Puzzles to help you become a computational thinker

- Conjuring with Computation

- Learn the basics of computer science through magic tricks

Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish a new post to the CS4FN blog.

This blog is funded by EPSRC on research agreement EP/W033615/1.