Back in its early days, after the war, women played a pivotal role in the computing industry, originally as skilled computer operators. Soon they started to be taken on as skilled computer programmers too. The myth that programming is boys thing came much later. Originally it was very much a job for women too. Dina St Johnston was one such early programmer. And she personally went on to kick-start the whole independent UK software industry!

On leaving school, interested in maths, science and machines, she went to work for a metallurgy research company, and in parallel gained a University of London external Maths degree, but eventually moved on to get a job ultimately as a programmer at an early computer manufacturer, Elliot Brothers in 1053. Early software she was involved in writing was very varied, but whatever the application she excelled. For example, she was responsible for writing an in-house payroll program, as well as code for a dedicated direction finding computer of the Royal Navy. The latter was a system that used the direction of radio signals picked up by receivers at different listening stations to work out where the source was (whether friend or foe). She also wrote software for the first computer to be used by a local government, Norwich City Council. She had the kind of attention to detail and logical thinking skills that meant she quickly became an incredibly good programmer, able to write correct code. Bugs for others to find in her code were rare. “Whereas the rest of us tested programs to find the faults, she tested them to demonstrate that they worked.”

Towards the end of the 1960s though she realised there was a big opportunity, a gap in the market, for someone with programming skills and a strong entrepreneurial spirit like her. All UK application software at the time was developed either by computer manufacturers like Elliot Brothers, by service companies selling time on their computers, by consultancy firms or in-house by people working directly for the companies who bought the computers. There was, she saw, potential to create a whole new industry: an applications software industry. What there was a need for, were independent software companies whose purpose was to write bespoke application programs that were just what a client company needed, for any who needed it, big or small. She therefore left Elliot Brothers and founded her own company (named after her maiden name), Vaughan Programming Services, to do just that.

Despite starting out working from her dining room table, it was a big success, working in a lot of different application areas over the subsequent decades, with clients including massive organisations such as the BBC, BAA, Unilever, GEC, the nuclear industry (she wrote software for what is now called Sellafield, then the first ever industrial nuclear power plant), the RAF and British Rail. Part of the reason she made it work was she was a programmer who was “happy to go round a steel works in a hard hat”, She made sure she understood her clients needs in a direct hands-on way.

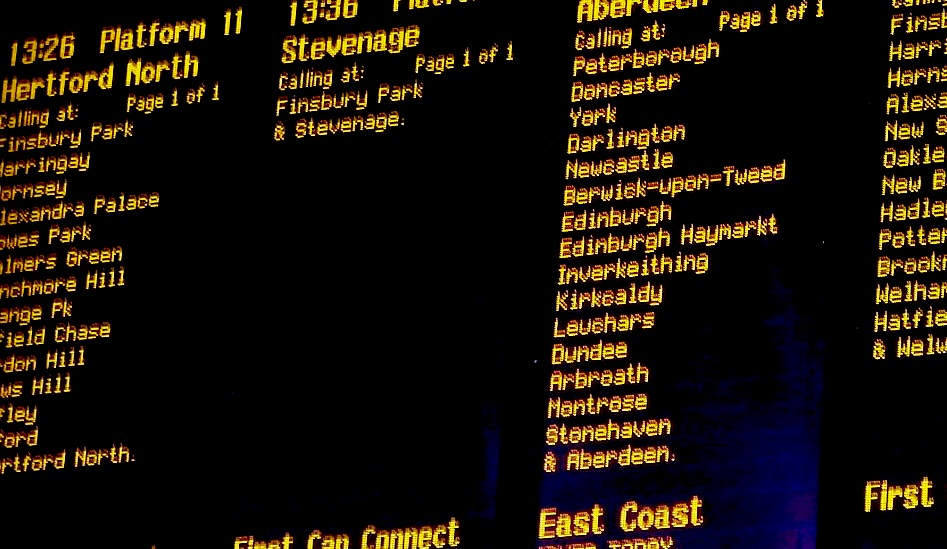

Eventually, Dina’s company started to specialise in transport information systems and that is where it really made its name…with early work for example on the passenger display boards at London Bridge, but eventually to hundreds of stations, driven from a master timetable system. So next time you are in a train station or airport, looking at the departure board, think of Dina, as it was her company that wrote the code driving the forerunner of the display you are looking at.

More than that though, the whole idea of a separate software industry to create whatever programs were needed for whoever needed them, started with her. If you are a girl wondering about whether a software industry job is for you, as she showed, there is absolutely no reason why it should not be. Dina excelled, so can you.

by Paul Curzon, Queen Mary University of London

More on …

- Tech Entrepreneurship

- The women are still here

- Women in Computing at the Science Museum [EXTERNAL]

- An obituary of Dina can be found in The Computer Journal (2009) 52 (3): 378-387 (though needs access rights)

Magazines …

Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish a new post to the CS4FN blog.

This page and talk are funded by EPSRC on research agreement EP/W033615/1.