Continuing a series of blogs on what to do with all that lego scattered over the floor: learn some computer science…

We saw in the last post how images are stored as pixels – the equivalent of square or round lego blocks of different colours laid out in a grid like a mosaic. By giving each colour a number and drawing out a gird of numbers we give ourself a map to recreate the picture from. Turning that grid of numbers into a list (and knowing the size of the rectangle that is the image) we can store the image as a file of numbers, and send it to someone else to recreate.

Of course, we didn’t really need that grid of numbers at all as it is the list we really need. A different (possibly quicker) way to create the list of numbers is work through the picture a brick at a time, row by row and find a brick of the same colour. Then make a long line of those bricks matching the ones in the lego image, keeping them in the same order as in the image. That long line of bricks is a different representation of the image as a list instead of as a grid. As long as we keep the bricks in order we can regenerate the image. By writing down the number of the colour of each brick we can turn the list of bricks into another representation – the list of numbers. Again the original lego image can be recreated from the numbers.

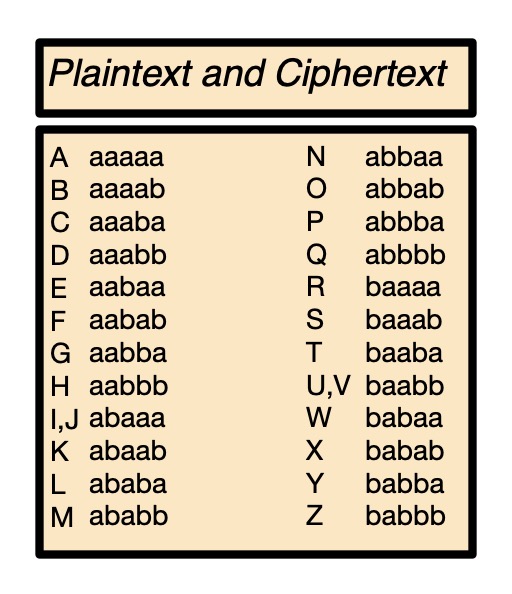

Colour look-up table: Black 0: Blue 1: Yellow 2: Green 3: Brown 4

Image by CS4FN

The trouble with this is for any decent size image it is a long list of numbers – made very obvious by the very long line of lego bricks now covering your living room floor. There is an easy thing to do to make them take less space. Often you will see that there is a run of the same coloured lego bricks in the line. So when putting them out, stack adjacent bricks of the same colour together in a pile, only starting a new pile if the bricks change colour. If eventually we get to more bricks of the original colour, they start their own new pile. This allows the line of bricks to take up far less space on the floor. (We have essentially compressed our image – made it take less storage space, at least here less floor space).

Image by CS4FN

Now when we create the list of numbers (so we can share the image, or pack all the lego away but still be able to recreate the image), we count how many bricks are in each pile. We can then write out a list to represent the numbers something like 7 blue, 1 green, … Of course we can replace the colours by numbers that represent them too using our key that gives a number to each colour (as above).

If we are using 1 to mean blue and the line of bricks starts with a pile of seven black bricks then write down a pair of numbers 7 1 to mean “a pile of seven blue bricks”. If this is followed by 1 green bricks with 3 being used for green then we next write down 1 3, to mean a pile of 1 green bricks and so on. As long as there are lots of runs of bricks (pixels) of the same colour then this will use far less numbers to store than the original:

7 1 1 3 6 1 2 3 1 1 1 2 3 1 2 3 2 2 3 1 2 3 …

We have compressed our image file and it will now be much quicker to send to a friend. The picture can still be rebuilt though as we have not lost any information at all in doing this (it is called a lossless data compression algorithm). The actual algorithm we have been following is called run-length encoding.

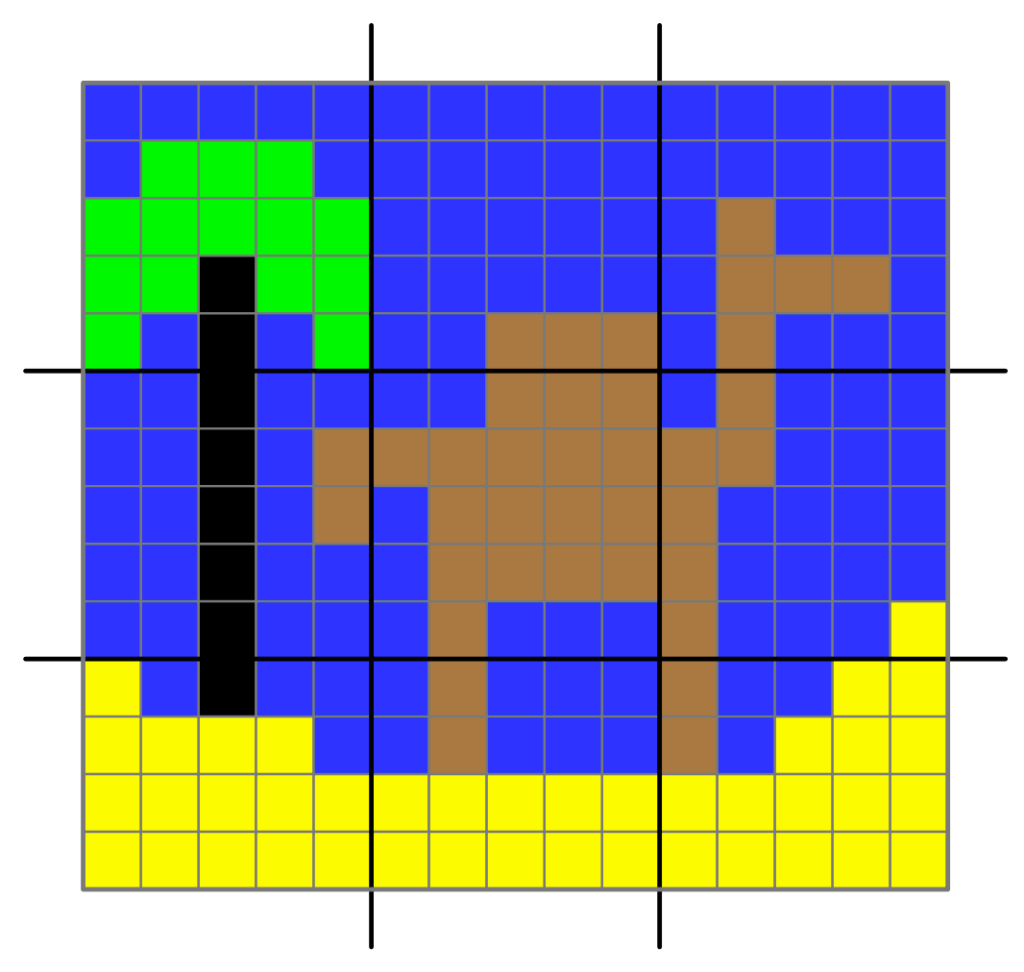

Of course, for some images, it may take more not less numbers if the picture changes colour nearly every brick (as in the middle of our giraffe picture). However, as long as there are large patches of similar colours then it will do better.

There are always tweaks you can do to algorithms that may improve the algorithm in some circumstances. For example in the above we jumped back to the start of the row when we got to the end. An alternative would be to snake down the image, working along the adjacent rows in opposite directions. That could improve run-length encoding for some images because patches of colour are likely the same as the row below, so this may allow us to continue some runs. Perhaps you can come up with other ways to make a better image compression algorithm

Run-length encoding is a very simple compression algorithm but it shows how the same information can be stored using a different representation in a way that takes up less space (so can be shared more quickly) – and that is what compression is all about. Other more complex compression algorithms use this algorithm as one element of the full algorithm.

Activities

Make this picture in lego (or colouring in on squared paper or in a spreadsheet if you don’t have the lego). Then convert it to a representation consisting of a line of piles of bricks and then create the compressed numbered list.

Image by CS4FN

Make your own lego images, encode and compress them and send the list of numbers to a friend to recreate.

Paul Curzon, Queen Mary University of London

More on …

- Lego Computer Science

- Part of a series featuring featuring pixel puzzles,compression algorithms, number representation,gray code, binary, logic and computation.

- Lego Art at lego.com. [EXTERNAL]

- Pixel puzzles (no lego needed, just coloured pens or spreadsheets) at https://teachinglondoncomputing.org/pixel-puzzles/

Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish a new post to the CS4FN blog.

This blog is funded by EPSRC on research agreement EP/W033615/1.

This post was funded by UKRI, through grant EP/K040251/2 held by Professor Ursula Martin, and forms part of a broader project on the development and impact of computing.