Puzzle design credit: https://puzzlemaker.discoveryeducation.com/criss-cross/

Download and print the puzzle

- UK readers please use this file: Music and AI Kriss Kross puzzle A4 (PDF)

- US readers (or anyone whose printer uses 8½x11 inch paper) please use this file: Music and AI Kriss Kross puzzle 8½x11-US (PDF).

Answers are at the bottom of https://cs4fn.blog/bitof6 where you can also read a copy of the magazine articles about Music and Artificial Intelligence.

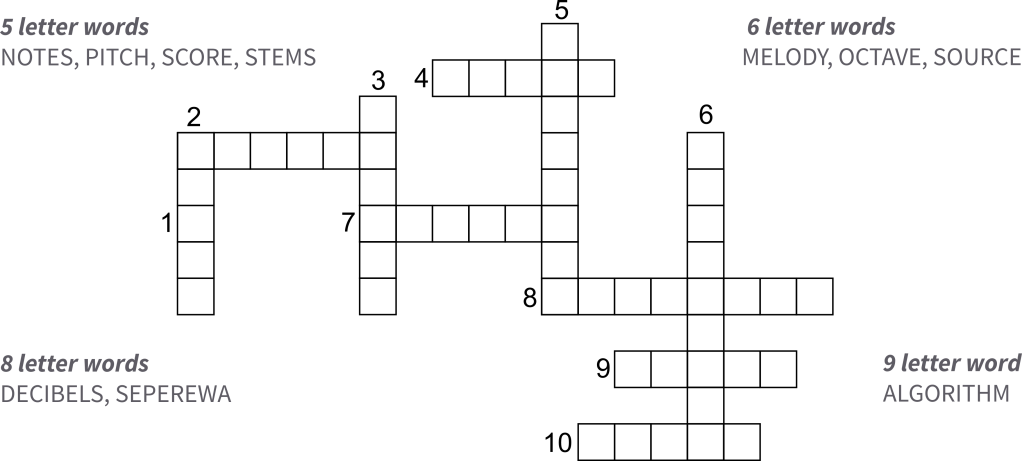

Clues

- 1. _ _ _ _ _ a piece of text with musical symbols instead of letters that tells a performer which

notes to play, also a piece of music that accompanies a film (5 letters) - 2. and 10. _ _ _ _ _ _ (6 letters) separation is when computer scientists use AI to take a piece of music

and split it into its _ _ _ _ _ (5 letters) – read more about this in ‘Separate your stems‘ - 3. The _ _ _ _ _ _ is the main part of the tune you might sing along to (6 letters)

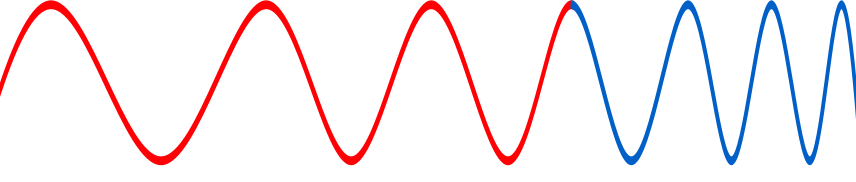

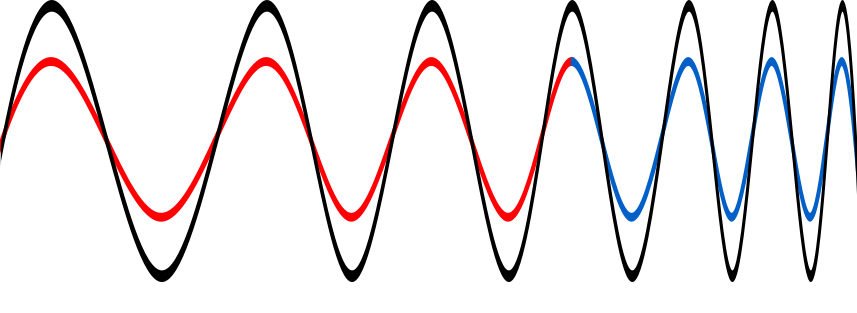

- 4. A piece of music is made up of lots of different _ _ _ _ _ (5 letters)

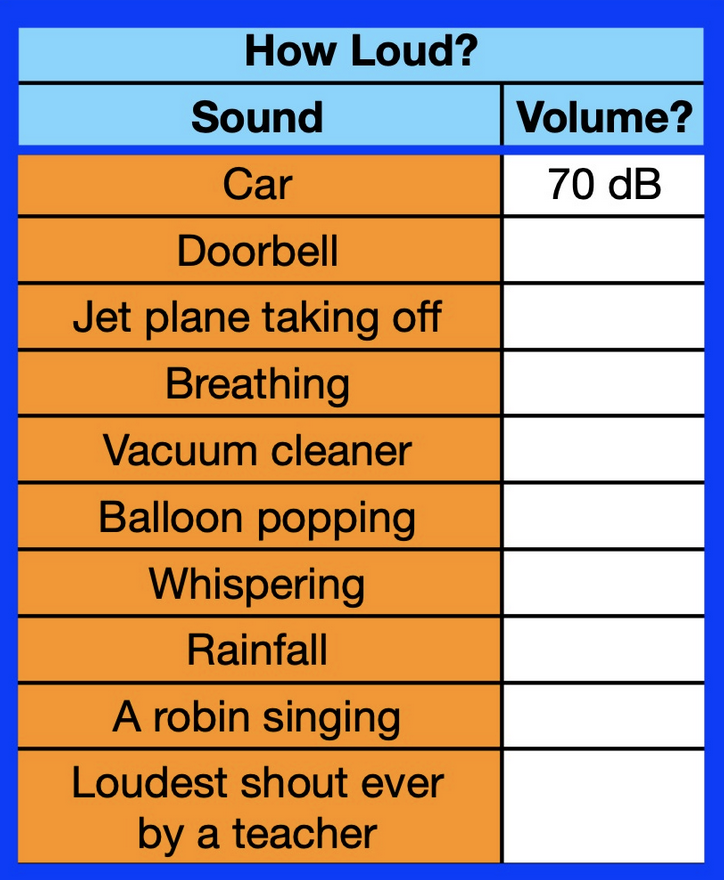

- 5. We measure how loud something is in _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ (8 letters)

- 6. A sequence of instructions that tell a computer what to do _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ (9 letters)

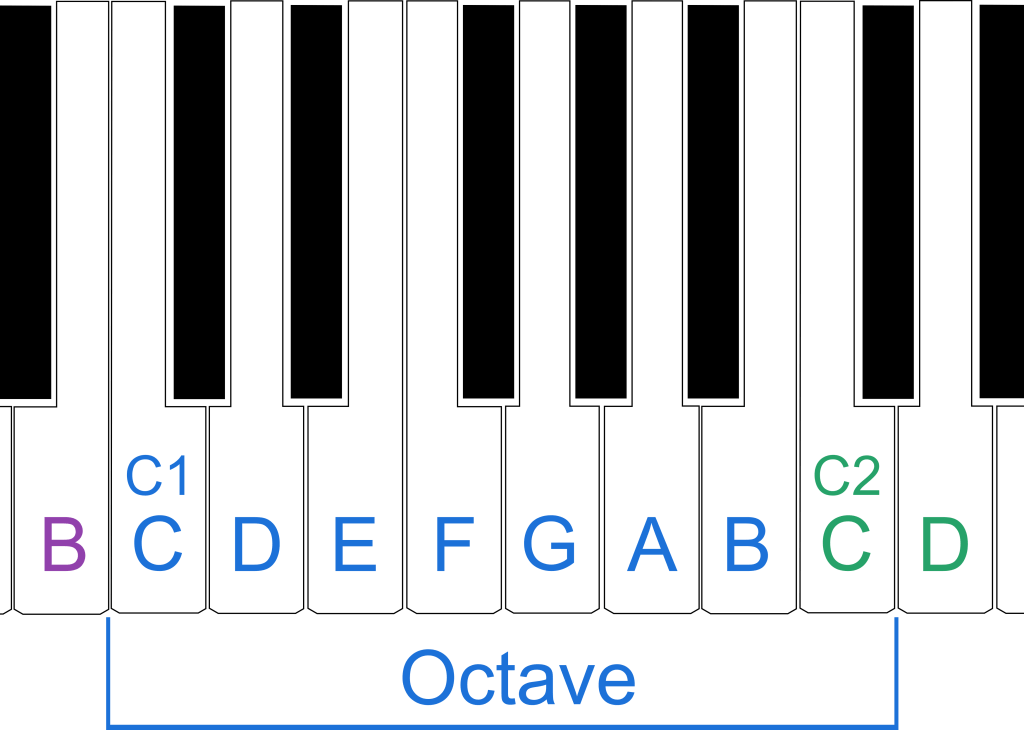

- 7. If you halve the length of a guitar string the note is an _ _ _ _ _ _ (6 letters)

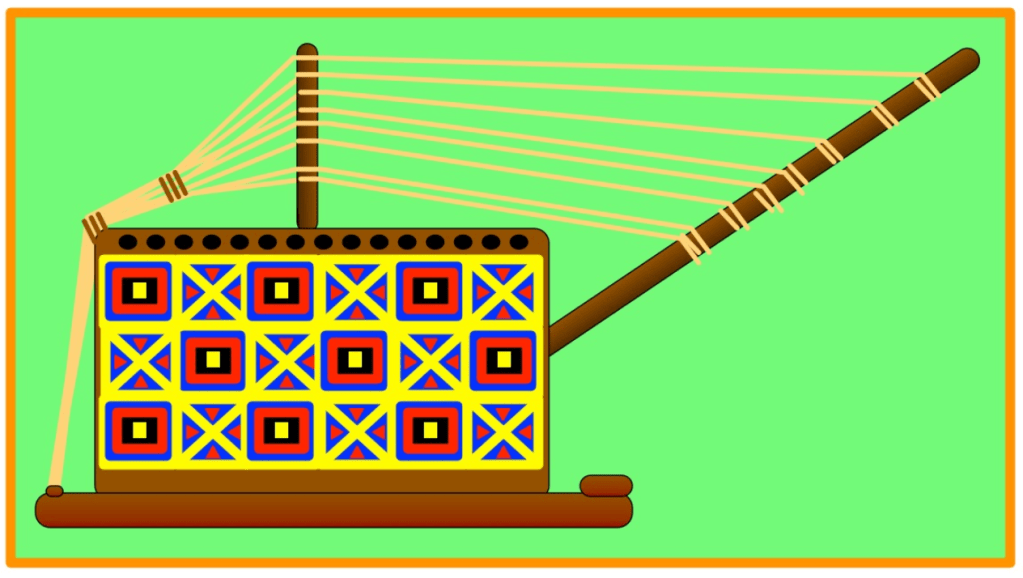

- 8. A guitar-like harp-lute from Ghana _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ (8 letters) – read more about this in ‘The day the music didn’t die‘

- 9. How high or how low a musical note is _ _ _ _ _ (5 letters)

- 10. (see 2.)

Jo Brodie, Queen Mary University of London

More on…

- Even more kriss kross puzzles (on our sister site, Teaching London Computing)

We have LOTS of articles about music, audio and computer science. Have a look in these themed portals for more:

- Music and AI

- Music, Digital or Not

- Audio Engineering

- Read more about Music and AI in our mini-magazine “A Bit of CS4FN” issue 6

Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish a new post to the CS4FN blog.