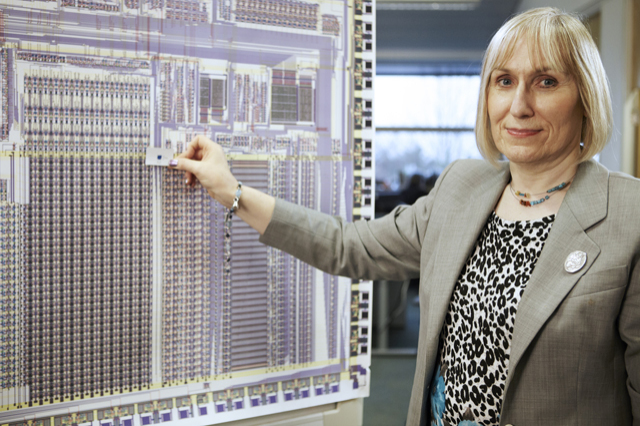

Chip design that changed the world

Some people’s innovations are so amazing it is hard to know where to start. Sophie Wilson is like that. She helped kick start the original 80’s BBC micro computer craze, then went on to help design the chips in virtually every smartphone ever made. Her more recent innovations are the backbone that is keeping broadband infrastructure going. The amount of money her innovations have made easily runs into tens of billions of dollars, and the companies she helped succeed make hundreds of billions of dollars. It all started with her feeding cows!

While still a student Sophie spent a summer designing a system that could automatically feed cows. It was powered by a microcomputer called the MOS 6502: one of the first really cheap chips. As a result Sophie gained experience in both programming using the 6502’s set of instructions but also embedded computers: the idea that computers can disappear into other everyday objects. After university she quickly got a job as a lead designer at Acorn Computers and extended their version of the BASIC language, adding, for example, a way to name procedures so that it was easier to write large programs by breaking them up into smaller, manageable parts.

Acorn needed a new version of their microcomputer, based on the 6502 processor, to bid for a contract with the BBC for a project to inspire people about the fun of coding. Her boss challenged her to design it and get it working, all in only a week. He also told her someone else in the team had already said they could do it. Taking up the challenge she built the hardware in a few days, soldering while watching the Royal Wedding of Charles and Diana on TV. With a day to go there were still bugs in the software, so she worked through the night debugging. She succeeded and within the week of her taking up the challenge it worked! As a result Acorn won a contract from the BBC, the BBC micro was born and a whole generation were subsequently inspired to code. Many computer scientists, still remember the BBC micro fondly 30 years later.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/101251639@N02/9669448671, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=68622523

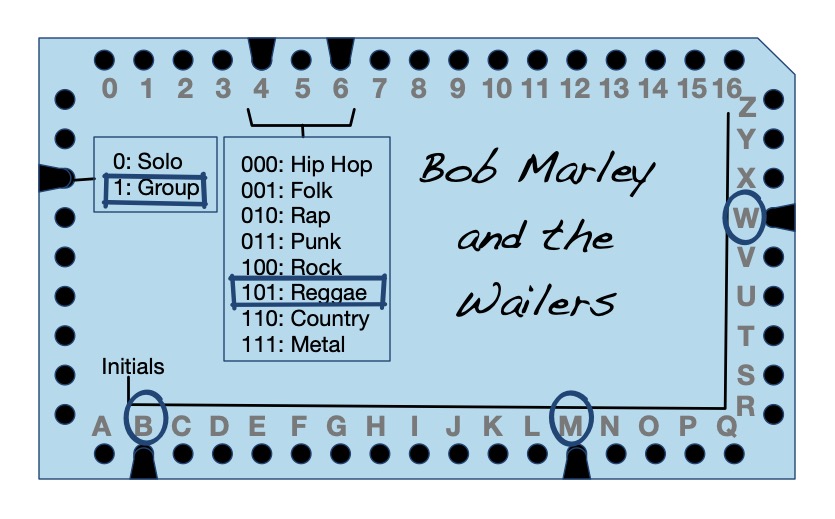

That would be an amazing lifetime achievement for anyone. Sophie went on to even greater things. Acorn morphed into the company ARM on the back of more of her innovations. Ultimately this was about returning to the idea of embedded computers. The Acorn team realised that embedded computers were the future. As ARM they have done more than anyone to make embedded computing a ubiquitous reality. They set about designing a new chip based on the idea of Reduced Instruction Set Computing (RISC). The trend up to that point was to add ever more complex instructions to the set of programming instructions that computer architectures supported. The result was bloated systems that were hungry for power. The idea behind RISC chips was to do the opposite and design a chip with a small but powerful instruction set. Sophie’s colleague Steve Furber set to work designing the chip’s architecture – essentially the hardware. Sophie herself designed the instructions it had to support – its lowest level programming language. The problem was to come up with the right set of instructions so that each could be executed really, really quickly – getting as much work done in as few clock cycles as possible. Those instructions also had to be versatile enough so that when sequenced together they could do more complicated things quickly too. Other teams from big companies had been struggling to do this well despite all their clout, money and powerful computer mainframes to work on the problem. Sophie did it in her head. She wrote a simulator for it in her BBC BASIC running on the BBC Micro. The resulting architecture and its descendants took over the world, with ARM’s RISC chips running 95% of all smartphones. If you have a smartphone you are probably using an ARM chip. They are also used in game controllers and tablets, drones, televisions, smart cars and homes, smartwatches and fitness trackers. All these applications, and embedded computers generally, need chips that combine speed with low energy needs. That is what RISC delivered allowing the revolution to start.

If you want to thank anyone for your personal mobile devices, not to mention the way our cars, homes, streets and work are now full of helpful gadgets, start by thanking Sophie…and she’s not finished yet!

Paul Curzon, Queen Mary University of London

More on …

- LGBTQ+ [part of our Teaching London Computing Diversity pages]

- The algorithm that dare not speak its name

- Tech Entrepreneurship

Related Magazines …

Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish a new post to the CS4FN blog.

This blog is funded by EPSRC on research agreement EP/W033615/1.