Continuing a series of blogs on what to do with all that lego scattered over the floor: learn some computer science…how do computers represent numbers? Using binary.

We’ve seen that numbers, in fact any data, can be represented in lots of different ways. We represent numbers using ten digits, but we could use more or less digits. Even if we restrict ourselves to just two digits then there are lots of ways to represent numbers using them. We previously saw Gray code, which is a way that makes it easy to count using electronics as it only involves changing one digit as we count from one number to the next. However, we use numbers for more than just counting. We want to do arithmetic with them too. Computers therefore use the two symbols in a different way to Gray Code.

With ten digits it turned out that using our place-value system is a really good choice for storing large numbers and doing arithmetic on them. It leads to fairly simple algorithms to do addition, subtraction and so on, even of big numbers. We learnt them in primary school.

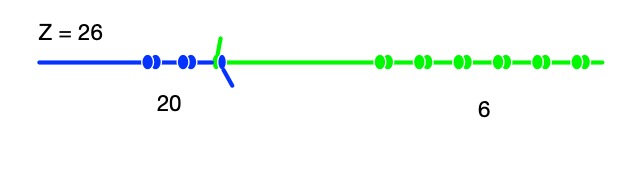

We can use the same ideas, and so similar algorithms, when we only allow ourselves two digits. When we do we get the pattern of counting we call binary. We can make the pattern out of lego bricks using two different colours for the two digits, 1 and 0:

Image by CS4FN

Place-value patterns

The pattern at first seems fairly random, but it actually follows the same pattern as counting in decimal.

In decimal we label the columns: ones, tens, hundreds and so on. This is because we have 10 digits (0-9) so when we get up to nine we have run out of digits so to add one more go back to zero in the ones column and carry one into the tens column instead. A one in the tens column has the value of ten not just one. Likewise, a one in the hundreds column has the value of a hundred not ten (as when we get up to 99, in a similar way, we need to expand into a new column to add one more).

In binary, we only have two digits so have to carry sooner. We can count 0, 1, but have then run out of digits, so have to carry into the next column for 2. It therefore becomes 10 where now the second column is a TWOs column not a TENs column as in decimal. We can carry on counting: … 10, 11 (ie 2, 3) and again then need to carry into a new column for 4 as we have run out of digits again but now in both the ONEs and TWOs columns. So the binary number for 4 is 100, where the third column is the FOURs column and so a one there stands for 4. The next time we have to use a new column is at 8 (when our above sequence runs out) and then 16. Whereas in decimal the column headings are powers of ten: ONEs, TENs, HUNDREDs, THOUSANDs, …, in binary the column headings are powers of two: ONEs, TWOs, FOURs, EIGHTs, SIXTEENs, …

Just as there are fairly simple algorithms to do arithmetic with decimal, there are also similar simple algorithms to do arithmetic in binary. That makes binary a convenient representation for numbers.

I Ching Binary Lego

We can of course use anything as our symbol for 0 and for 1 and through history many different symbols have been used. One of the earliest known uses of binary was in an Ancient Chinese text called the I Ching. It was to predict the future a bit like horoscopes, but based on a series of symbols that turn out to be binary. They involve what are called hexagrams – symbols made of six rows. Imagine each row is a stick of green bamboo. It can either be broken into two so with a gap in the middle (a 0) or unbroken with no gap (a 1). When ordered using the binary code, you then get the sequence as follows:

Image by CS4FN

Now each row stands for a digit: the bottom row is the ONEs, the next is TWOs, then the FOURs row and so on.

Using all six rows you can create 64 different symbols, so count from 0 to 63. Perhaps you can work out (and make in lego) the full I Ching binary pattern counting from 0 to 64.

Binary in Computers

Computers use binary to represent numbers but just using different symbols (not lego bricks or bamboo stalks). In a computer, a switch being on or a voltage being high stands for a 1 and a switch being off or a voltage being low stands for 0. Other than those different symbols for 1 and 0 being used, numbers are stored as binary using exactly the same pattern as with our red and blue bricks, and the I Ching pattern of yellow and green bricks.

All data in a computer is really just represented as electrical signals. However, you can think of a binary number stored in a computer as just a line of red and blue bricks. In fact, a computer memory is just like billions of red and blue lego bricks divided into sections for each separate number.

All other data, whether pictures, sounds or video can be stored as numbers, so once you have a way to represent numbers like this, everything else can be represented using them.

Paul Curzon, Queen Mary University of London

More on …

- Lego Computer Science

- Part of a series featuring featuring pixel puzzles,

compression algorithms, number representation,

gray code, binary, logic and computation.

- Part of a series featuring featuring pixel puzzles,

Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish a new post to the CS4FN blog.

This blog is funded by EPSRC on research agreement EP/W033615/1.

This post was funded by UKRI, through grant EP/K040251/2 held by Professor Ursula Martin, and forms part of a broader project on the development and impact of computing.