Computer tools based on what are called “Bayesian networks” give accurate ways to determine how likely things are. For example, they give a good way, based on evidence, to determine how likely a given person has COVID. As you collect more evidence, the probability the network gives becomes more accurate.

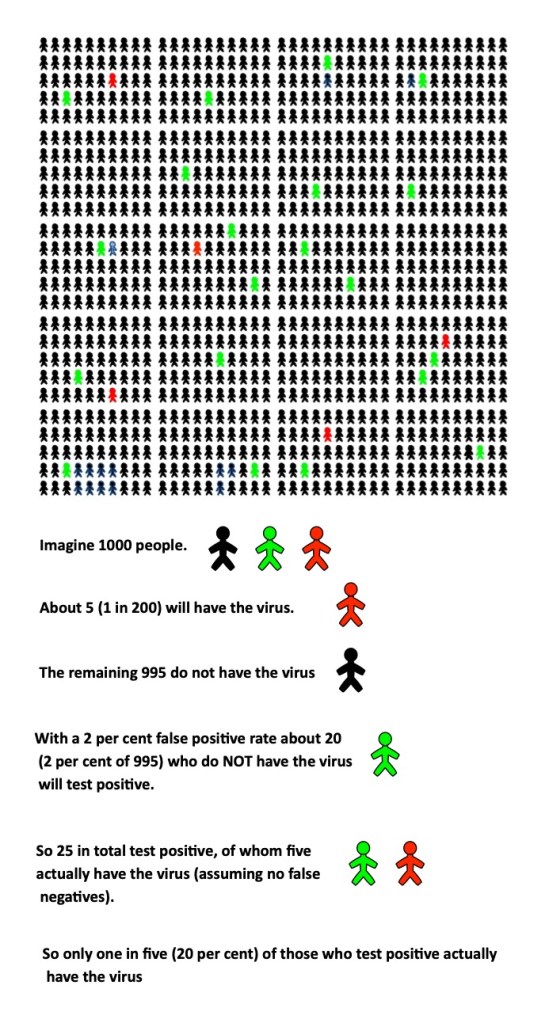

How likely is it that you have COVID? There is lots of evidence you might collect to decide whether or not you do. It causes many (but not all) people to cough. So if you do have the a cough that is useful evidence. Other things like flu, however, also cause people to cough. Catching COVID is also known to be caused by breathing the same air as infected people. The more socialising you have done the higher the chance you have caught it, but also the more people in your area with the disease the more likely it is that you have caught it by socialising. You can also take a test – having COVID will cause a positive result. However, tests are not fully accurate, so even with a positive test you may or may not have COVID…

Deciding how likely it is you have COVID relies on knowing lots of facts about the causes of COVID and about the symptoms it causes. It also relies on knowing the probabilities of things such as how likely it is that COVID causes a cough. Finally it relies on knowing lots of facts about you such as whether you have had a positive test result or not.

A Bayesian network is just a way of drawing a diagram that collects all this information in one place. Once created it can be used to determine how likely things like whether you have COVID are to be true based on known facts, known causes, and the chances of one thing causing another. It gives a powerful way to reason about these facts and probabilities based on “causal relationships”. That reasoning allows accurate probabilities to be calculated about the things you are interested in knowing. Given I have a cough and no other symptoms, have had a negative test but have recently socialised outside my family, am I 80 per cent certain I have COVID or is the chance I have it only 2 per cent?

We can take all the evidence for and against our having the virus and draw a Bayesian network as shown in the diagram. For each bubble the percentages show the chance that for a random person in the population this thing is currently true. Arrows show which things can cause others. So, in the diagram, this means that 0.5 per cent of the population currently have the virus (as 1 in 200 have the virus, so probability 0.005, and to turn a probability into a percentage you just multiply by 100); 0.4 per cent of the population have been in recent contact with an infected person; 10 per cent have a cough; 2 per cent have flu, and so on. This is all general evidence we can collect about the country as a whole. (Note we have made up these numbers for the example as they may change over time, but they are the kinds of data scientists collect to help policy makers make decisions.)

The model also includes probabilities not shown, like the chance of a person getting the virus if they have been in recent contact with an infected person and the probability of a positive test depending on whether they do, or do not, have the virus. Once a particular Bayesian network like this has been created it can form the basis of a decision making tool that does all the calculations.

We then want to know about you. Do you have a cough, have you lost your sense of taste or smell, what was the result of your test, and have you been in contact with an infected relative? From this information, we can update the probabilities in the Bayesian network (using a theorem called Bayes’ theorem) to give a new probability for how likely it is that you have the virus. Computer software can do this for us, though the more complicated the Bayesian network, the longer it takes to do all the calculations.

The result, though, is that the computer can give you a personalised risk assessment of how likely it is that you have the virus based on the specific evidence about you. You can find such a comprehensive personal COVID risk calculator, based on a Bayesian network with much more data, at covid19.apps.agenarisk.com/

Norman Fenton and Paul Curzon, Queen Mary University of London, Spring 2021

More on …

Related Magazine …

This post and issue 27 of the cs4fn magazine have been funded by EPSRC as part of the PAMBAYESIAN project on research agreement EP/P009964/1.

Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish a new post to the CS4FN blog.

This blog is funded by EPSRC on research agreement EP/W033615/1.