Back in the 1960s there was an AI winter…after lots of hype about how Artificial Intelligence tools would soon be changing the world, the hype fell short of the reality and the bubble burst, funding disappeared and progress stalled. One of the things that contributed was a simple theoretical result, the apparent shortcomings of a little device called a perceptron. It was the computational equivalent of an artificial brain cell and all the hype had been built on its shoulders. Now, variations of perceptrons are the foundation of neural networks and machine learning tools which are taking over the world…so what went wrong in the 1960s? A much misunderstood mathematical result about what a perceptron can and can’t do was part of the problem!

The idea of a perceptron dates back to the 1940s but Frank Rosenblatt, a researcher at Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory, first built one in 1958 and so popularised the idea. A perceptron can be thought of as a simple gadget, or as an algorithm for classifying things. The basic idea is it has lots of inputs of 0 or 1s and one output, also of 0 or 1 (so equivalent to taking true / false inputs and returning a true / false output). So for example, a perceptron working as a classifier of whether something was a mammal or not, might have inputs representing lots of features of an animal. These would be coded as 1 to mean that feature was true of the animal or 0 to mean false: INPUT: “A cow gives birth to live young” (true: 1), “A cow has feathers” (false: 0), “A cow has hair” (true: 1), “A cow lays eggs” (false: 0), “etc. OUTPUT: (true: 1) meaning a cow has been classified as a mammal.

A perceptron makes decisions by applying weightings to all the inputs that increase the importance of some, and lesson the importance of others. It then adds the results together also adding in a fixed value, bias. If the sum it calculates is greater then or equal to 0 then it outputs 1, otherwise it outputs 0. Each perceptron has different values for the bias and the weightings, depending on what it does. A simple perceptron is just computing the following bit of code for inputs in1, in2, in3 etc (where we use a full stop to mean multiply):

IF bias + w1.in1 + w2.in2 + w3.in3 ... >= 0

THEN OUTPUT O

ELSE OUTPUT 1Because it uses binary (1s and 0s), this version is called a binary classifier. You can set a perceptron’s weights, essentially programming it to do a particular job, or you can let it learn the weightings (by applying learning algorithms to the weightings). In the latter case it learns for itself the right answers. Here, we are interested in the fundamental limits of what perceptrons could possibly learn to do, so do not need to focus on the learning side just on what a perceptron’s limits are. If we can’t program it to do something then it can’t learn to do it either!

Machines made of lots of perceptrons were created and experiments were done with them to show what AIs could do. For example, Rosenblatt built one called Tobermory with 12,000 weights designed to do speech recognition. However, you can also explore the limits of what can be done computationally through theory: using maths and logic, rather than just by invention and experiments, and that kind of theoretical computer science was what others did about perceptrons. A key question in theoretical computer science about computers is “What is computable?” Can your new invention compute anything a normal computer can? Alan Turing had previously proved an important result about the limits of what any computer could do, so what about an artificial intelligence made of perceptrons? Could it learn to do anything a computer could or was it less powerful than that?

As a perceptron is something that takes 1s and 0s and returns a 1 or 0, it is a way of implementing logic: AND gates, OR gates, NOT gates and so on. If it can be used to implement all the basic logical operators then a machine made of perceptrons can do anything a computer can do, as computers are built up out of basic logical operators. So that raises a simple question, can you actually implement all the actual logical operators with perceptrons set appropriately. If not then no perceptron machine will ever be as powerful as a computer made of logic gates! Two of the giants of the area Marvin Minsky and Seymour Papert investigated this. What they discovered contributed to the AI winter (but only because the result was misunderstood!)

Let us see what it involves. First, can we implement an AND gate with appropriate weightings and bias values with a perceptron? An AND gate has the following truth table, so that it only outputs 1 if both its inputs are 1:

So to implement it with a perceptron, we need to come up with positive or negative number for, bias, and other numbers for w1 and w2, that weight the two inputs. The numbers chosen need to lead to it giving output 1 only when the two inputs (in1 and in2) are 1 and otherwise giving output, 0.

bias + w1.in1 + w2.in2 >= 0 when in1 = 1 AND in2 = 1

bias + w1.in1 + w2.in2 < 0 otherwiseSee if you can work out the answer before reading on.

It can be done by setting the value of b to -2 and making both weightings, w1 and w2, value 1. Then, because the two inputs, in1, and in2 can only be 1 or 0, it takes both inputs being 1 to overcome b’s value of -2 and so raise the sum up to 0:

bias + w1.in1 + w2.in2 >= 0

-2 + 1.in1 + 1.in2 >= 0

-2 + 1.1 + 1.1 >=0So far so good. Now, see if you can work out weightings to make an OR gate and a NOT gate.

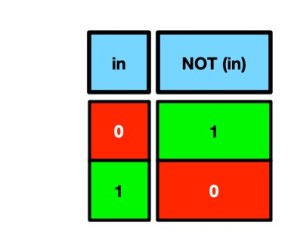

It is possible to implement both OR and NOT gate as a perceptron (see answers at the end).

However, Minsky and Papert proved that it was impossible to create another kind of logical operator, an XOR gate, with any values of bias and weightings in a perceptron. This a logic gate that has output 1 if its inputs are different, and outputs 0 if its inputs are the same.

Can you prove it is impossible?

They had seemingly shown that a perceptron could not compute everything a computer could. Perceptrons were not as expressive so not as powerful (and never could be as powerful) as a computer. There were things they could never learn to do, as there were things as simple as an XOR gate that they could not represent. This led some to believe the result meant AIs based on perceptrons were a dead end. It was better to just work with traditional computers and traditional computing (which by this point were much faster anyway). Along with the way that the promises of AI had been over-hyped with exaggerated expectations and the applications that had emerged so far had been fairly insignificant, this seemingly damming theoretical blow on top of all that led to funding for AI research drying up.

However, as current machine learning tools show, it was never that bad. The theoretical result had been misunderstood, and research into neural networks based on perceptrons eventually took off again in the 1990s

Minsky and Papert’s result is about what a single perceptron can do, not about what multiple ones can do together. More specifically, if you have perceptrons in a single layer, each with inputs just feeding its own outputs, the theoretical limitations apply. However, if you make multiple layers of perceptrons, with the outputs of one layer of perceptrons feeding into the next, the negative result no longer applies. After all, we can make AND, OR and NOT gates from perceptrons, and by wiring them together so the outputs of one are the inputs of the next one, then we can build an XOR gate just as we can with normal logic gates!

We can therefore build an XOR gate from perceptrons. We just need multi-layer perceptrons, an idea that was actually known about in the 1960s including by Minsky and Papert. However, without funding, making further progress became difficult and the AI winter started where little research was done on any kind of Artificial Intelligence, and so little progress was made.

The theoretical result about the limits of what perceptrons could do was an important and profound one, but the limitations of the result needed to be understood too, and that means understanding the assumptions it is based on (it is not about multi-layer perceptrons. Now AI is back, though arguably being over-hyped again, so perhaps we should learn from the past!. Theoretical work on the limits of what neural networks can and can’t do is an active research area that is as vital as ever. Let’s just make sure we understand what results mean before we jump to any conclusions. Right now theoretical results about AI need more funding not a new winter!

– Paul Curzon, Queen Mary University of London

This article is based on a introductory segment of a research seminar on the expressive power of graph neural networks by Przemek Walega, Queen Mary University of London, October 2025.

More on …

Answers

An OR gate perceptron can be made with bias = -1, w1 = w2 = 1

A NOT gate perceptron can be made with bias = 0, w1 = -1

Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish a new post to the CS4FN blog.

This blog is funded by EPSRC on research agreement EP/W033615/1.