by Jo Brodie, Queen Mary University of London

In 1977 NASA scientists at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory launched the interstellar probe Voyager 1 into space – and it just keeps going. It has now travelled 15 BILLION miles (24 billion kilometres), which is the furthest any human-made thing has ever travelled from Earth. It communicates with us here on Earth via radiowaves which can easily cross that massive distance between us. But even travelling at the speed* of light (all radiowaves travel at that speed) each radio transmission takes 22.5 hours, so if NASA scientists send a command they have to wait nearly two days for a response. (The Sun is ‘only’ 93 million miles away from Earth and its light takes about 8 minutes to reach us.)

FDS – The Flight Data System

The Voyager 1 probe has sensors to detect things like temperature or changes in magnetic fields, a camera to take pictures and a transmitter to send all this data back to the scientists on Earth. One of its three onboard computers (the Flight Data System, or FDS) takes that data, packages it up and transmits it as a stream of 1s and 0s to the waiting scientists back home who decode it. Voyager 1 is where it is because NASA wanted to send a probe out beyond the limits of our Solar System, into ‘interstellar space’ far away from the influence of our Sun to see what the environment is like there. It regularly sends back data updates which include information about its own health (how well its batteries are doing etc) along with the scientific data, packaged together into that radio transmission. NASA can also send up commands to its onboard computers too. Computers that were built in 1977!

The pale blue dot

a tiny dot about halfway down. That’s the Earth! Full details of this famous 1990 photo here.

Although its camera is no longer working its most famous photograph is this one, the Pale Blue Dot, a snapshot of every single person alive on the 14th of February 1990. However as Voyager 1 was 6 billion miles from home by then when it looked back at the Earth to take that photograph you might have some difficulty in spotting anyone! But they’re somewhere in there, inside that single pixel (actually less than a pixel!) which is our home.

As Voyager 1 moved further and further away from our own planet, visiting Jupiter and Saturn before travelling to our outer Solar System and then beyond, the probe continued to send data and receive commands from Earth.

The messages stopped making sense

All was going well, with the scientists and Voyager 1 ‘talking’ to one another, until November 2023 when the binary 1s and 0s it normally transmitted no longer had any meaningful pattern to them, it was gibberish. The scientists knew Voyager 1 was still ‘alive’ as it was able to send that signal but they didn’t know why its signal no longer made any sense. Given that the probe is nearly 50 years old and operating in a pretty harsh environment people wondered if that was the natural end of the project, but they were determined to try and re-establish normal contact with the probe if they could.

Searching for a solution

They pored over almost-50 year old paper instruction manuals and blueprints to try and work out what was wrong and it seemed that the problem lay in the FDS. Any scientific data being collected was not being correctly stored in the ‘parcel’ that was transmitted back to Earth, and so was lost – Voyager 1 was sending empty boxes. At that distance it’s too far to send an engineer up to switch it off and on again so instead they sent a command to try and restart things. The next message from Voyager 1 was a different string of 1s and 0s. Not quite the normal data they were hoping for, but also not entirely gibberish. A NASA scientist decoded it and found that Voyager 1 had sent a readout of the FDS’ memory. That told them where the problem was and that a damaged chip meant that part of its memory couldn’t be properly accessed. They had to move the memory from the damaged chip.

That’s easier said than done. There’s not much available space as the computers can only store 68 kilobytes of data in total (absolutely tiny compared to today’s computers and devices). There wasn’t one single place where NASA scientists could move the memory as a single block, instead they had to break it up into pieces and store it in different places. In order to do that they had to rewrite some of the code so that each separated piece contained information about how to find the next piece. Imagine if a library didn’t keep a record of where each book was, it would make it very hard to find and read the sequel!

Earlier this year NASA sent up a new command to Voyager 1, giving it instructions on how to move a portion of its memory from the damaged area to its new home(s) and waited to hear back. Two days later they got a response. It had worked! They were now receiving sensible data from the probe.

For a while they it was just basic ‘engineering data’ (about the probe’s status) but they knew their method worked and didn’t harm the distant traveller. They also knew they’d need to do a bit more work to get Voyager 1 to move more memory around in order for the probe to start sending back useful scientific data, and…

Success!

… …in May, NASA announced that scientific data from two of Voyager 1’s instruments was finally being sent back to Earth and in June the probe was fully operational. You can follow Voyager 1’s updates on Twitter / X via @NASAVoyager.

Did you know?

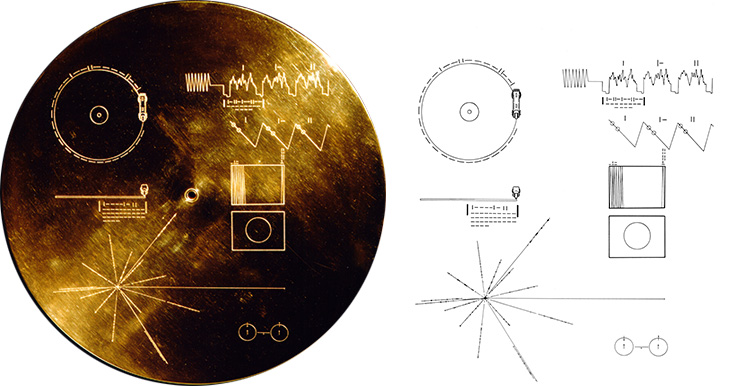

Both Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 carry with them a gold-plated record called ‘The Sounds of Earth‘ containing “sounds and images selected to portray the diversity of life and culture on Earth”. Hopefully any aliens encountering it will have a record player (but the Voyager craft do carry a spare needle!) Credit: NASA/JPL

References

Lots of articles helped in the writing of this one and you can download a PDF of them here. Featured image credit showing the Voyager spacecraft: NASA/JPL.

*radiowaves and light are part of the electromagnetic or ‘EM’ spectrum along with microwaves, gamma rays, X-rays, ultraviolet and infra red. All these waves travel at the same speed in a vacuum, the speed of light (300,000,000 metres per second, sometimes written as 3 x 108 m/s or (m s-1)), but the waves differ by their frequency and wavelength.

Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish a new post to the CS4FN blog.

EPSRC supports this blog through research grant EP/W033615/1.