Chatbots, knowing where your files are, and winning at noughts and crosses with artificial intelligence.

Welcome to Day 10 of our CS4FN Christmas Computing Advent Calendar. We are just under halfway through our 25 days of posts, one every day between now and Christmas. You can see all our previous posts in the panel with the Christmas tree at the end.

Today’s picture-theme is Holly (and ivy). Let’s see how I manage to link that to computer science 🙂

1. Holly – or Alexa or Siri

In the comedy TV series* Red Dwarf the spaceship has ‘Holly’ an intelligent computer who talks to the crew and answers their questions. Star Trek also has ‘Computer’ who can have quite technical conversations and give reports on the health of the ship and crew.

People are now quite familiar with talking to computers, or at least giving them commands. You might have heard of Alexa (Amazon) or Siri (Apple / iPhone) and you might even have talked to one of these virtual assistants yourself.

When this article (below) was written people were much less familiar with them. How can they know all the answers to people’s questions and why do they seem to have an intelligence?

Read the article and then play a game (see 3. Today’s Puzzle) to see if you think a piece of paper can be intelligent.

Meet the Chatterbots – talking to computers thanks to artificial intelligence and virtual assistants

Meet the Chatterbots – talking to computers thanks to artificial intelligence and virtual assistants

*also a book!

2. Are you a filing cabinet or a laundry basket?

People have different ways of saving information on their computers. Some university teachers found that when they asked their students to open a file from a particular directory their students were completely puzzled. It turned out that the (younger) students didn’t think about files and where to put them in the same way that their (older) teachers did, and the reason is partly the type of device teachers and students grew up with.

Older people grew up using computers where the best way to organise things was to save a file in a particular folder to make it easy to find it again. Sometimes there would be several folders. For example you might have a main folder for Homework, then a year folder for 2021, then folders inside for each month. In the December folder you’d put your december.doc file. The file has a file name (december.doc) and an ‘address’ (Homework/2021/December/). Pretty similar to the link to this blog post which also uses the / symbol to separate all the posts made in 2021, then December, then today.

To find your december.doc file again you’d just open each folder by following that path: first Homework, then 2021, then December – and there’s your file. It’s a bit like looking for a pair of socks in your house – first you need to open your front door and go into your home, then open your bedroom door, then open the sock drawer and there are your socks.

Younger people have grown up with devices that make it easy to search for any file. It doesn’t really matter where the file is so people used to these devices have never really needed to think about a file’s location. People can search for the file by name, by some words that are in the file, or the date range for when it was created, even the type of file. So many options.

The first way, that the teachers were using, is like a filing cabinet in an office, with documents neatly packed away in folders within folders. The second way is a bit more like a laundry basket where your socks might be all over the house but you can easily find the pair you want by typing ‘blue socks’ into the search bar.

Which way do you use?

In most cases either is fine and you can just choose whichever way of searching or finding their files that works for you. If you’re learning programming though it can be really helpful to know a bit about file paths because the code you’re creating might need to know exactly where a file is, so that it can read from it. So now some university teachers on STEM (science, technology, engineering and maths) and computing courses are also teaching their students how to use the filing cabinet method. It could be useful for them in their future careers.

Want to find out more about files / file names / file paths and directory structures? Have a look at this great little tutorial https://superbasics.beholder.uk/file-system/

As the author says “Many consumer devices try to conceal the underlying file system from the user (for example, smart phones and some tablet computers). Graphical interfaces, applications, and even search have all made it possible for people to use these devices without being concerned with file systems. When you study Computer Science, you must look behind these interfaces.”

You might be wondering what any of this has to do with ivy. Well, whenever I’ve seen a real folder structure on a Windows computer (you can see one here) I’ve often thought it looked a bit like ivy 😉

Further reading

File not found: A generation that grew up with Google is forcing professors to rethink their lesson plans (22 September 2021) The Verge

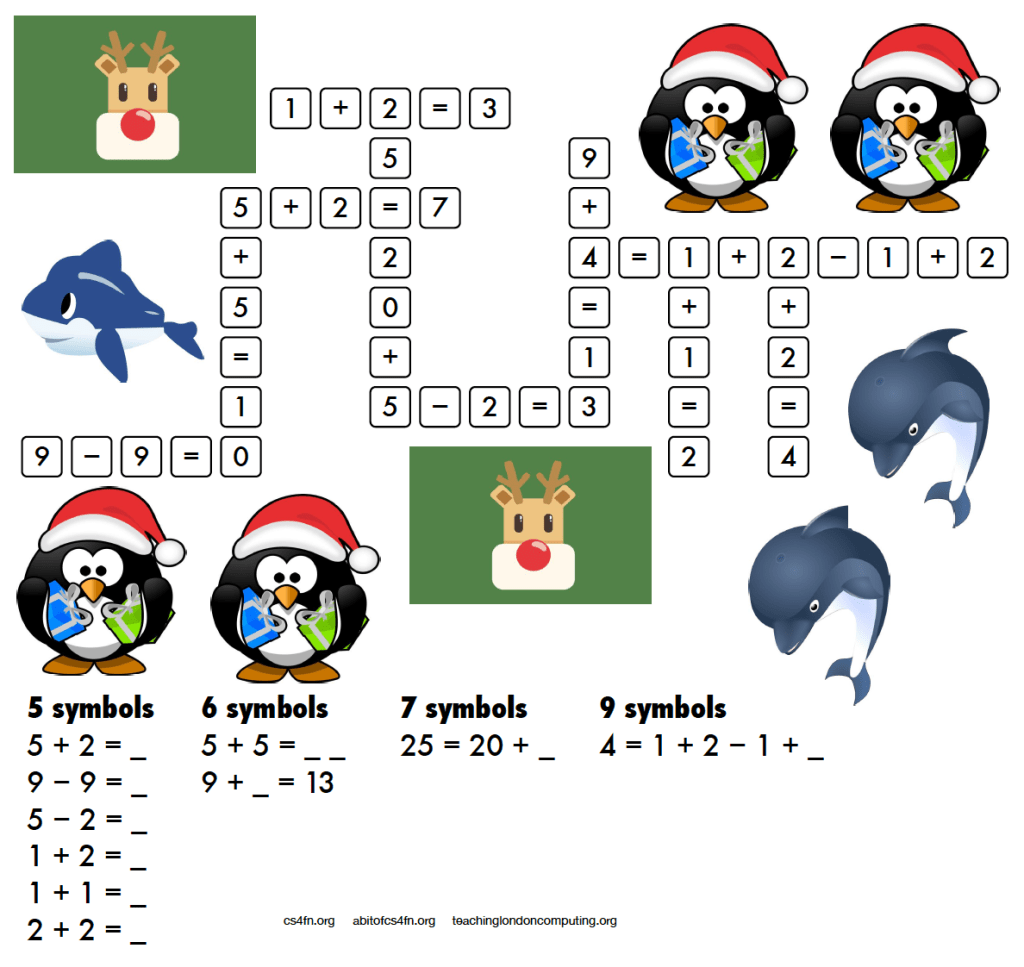

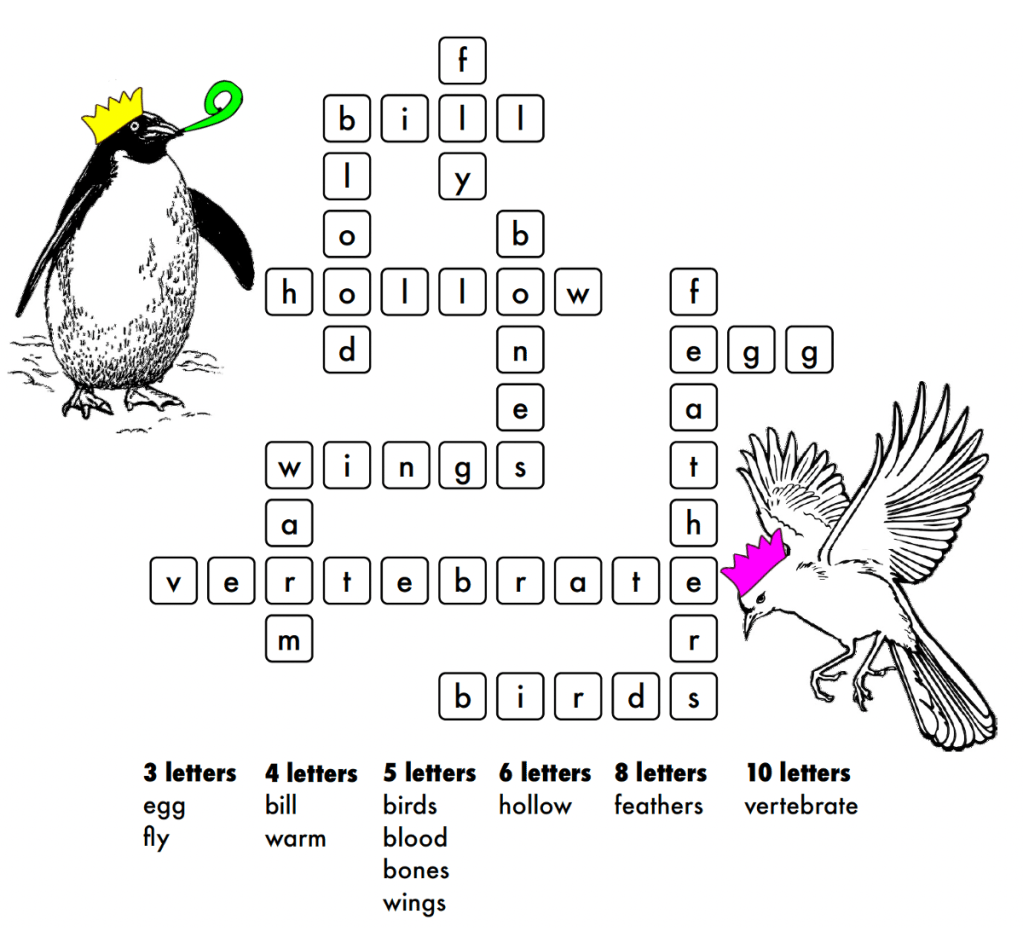

3. Today’s puzzle

Print or write out the instructions on page 5 of the PDF and challenge someone to a game of noughts and crosses… (there’s a good chance the bit of paper will win).

The Intelligent Piece of Paper activity.

4. Yesterday’s puzzle

The trick is based on a very old puzzle at least one early version of which was by Sam Lloyd. See this selection of vanishing puzzles for some variations. A very simple version of it appears in the Moscow Puzzles (puzzle 305) by Boris A. Kordemsky where a line is made to disappear.

In the picture above five medium-length lines become four longer lines. It looks like a line has disappeared but its length has just been spread among the other lines, lengthening them.

If you’d like to have a go at drawing your own disappearing puzzle have a look here.

EPSRC supports this blog through research grant EP/W033615/1.