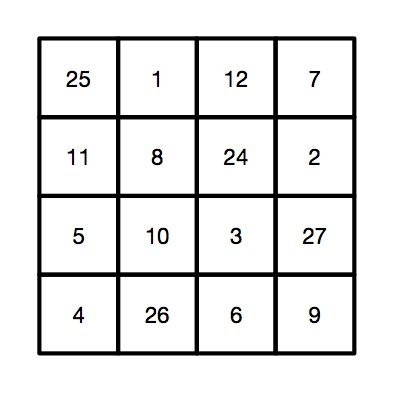

Victorian Computer Scientists, Ada Lovelace and Charles Babbage were interested in Magic Squares. We know this because a scrap of paper with mathematical doodles and scribbles on it in their handwriting has been discovered, and one of the doodles is a magic square like this one. In a magic square all the rows, columns and diagonals magically add to the same number. At some point, Ada and Charles were playing with magic squares together. Creating magic squares sounds hard, but perhaps not with a bit of algorithmic magic.

The magical effect

For this trick you ask a volunteer to pick a number. Instantly, on hearing it, you write out a personal four by four magic square for them based on that number. When finished the square contents adds to their chosen number in all the usual ways magic squares do. An impressive feat of superhuman mathematical skills that you can learn to do most instantly.

Making the magic

To perform this trick, first get your audience member to select a large two digit number. It helps if it is a reasonably large number, greater than 20, as you’re going to need to subtract 20 from it in a moment. Once you have the number you need to do a bit of mental arithmetic. You need an algorithm – a sequence of steps – to follow that given that number guarantees that you will get a correct magic square.

For our example, we will suppose the number you are given is 45, though it works with any number.

Let’s call the chosen number N (in our example: N is 45). You are going to calculate the following four numbers from it: N-21, N-20, N-19 and N-18, then put them in to a special, precomputed magic square pattern.

The magic algorithm

Sums like that aren’t too hard, but as you’ve got to do all this in your head, you need a special algorithm that makes it really easy. So here is an easy algorithm for working out those numbers.

- Start by working out N – 20. Subtracting 20 is quite easy. For our example number of 45, that is 25. This is our ‘ROOT’ value that we will build the rest from.

- N-19. Just add 1 to the root value (ROOT + 1). So 25 + 1 gives 26 for our example.

- N-18. Add 2 to the root value (ROOT + 2). So 25 + 2 gives 27.

- N-21. Subtract 1 from the root value (ROOT – 1). So 25 – 1 gives 24.

- Having worked out the 4 numbers created form the original chosen number, N, you need to stick them in the right place in a blank magic square, along with some other numbers you need to remember. It is the pattern you use to build your magic square from. It looks like the one to the right. To make this step easy, write this pattern on the piece of paper you write the final square on. Write the numbers in light pencil, over-writing the pencil as you do the trick so no-one knows at the end what you were doing.

A square grid of numbers like this is an example of what computer scientists call a data structure: a way to store data elements that makes it easy to do something useful: in this case making your friends think you are a maths superhero.

When you perform this trick, fill in the numbers in the 4 by 4 grid in a random, haphazard way, making it look like you are doing lots of complicated calculations quickly in your head.

Finally, to prove to everyone it is a magic square with the right properties, go through each row, column and diagonal, adding them up and writing in the answers around the edge of the square, so that everyone can see it works.

The final magic square for chosen number 45

So, for our example, we would get the following square, where all the rows, columns and diagonals add to our audience selected number of 45.

Why does it work?

If you look at the preset numbers in each row, column and diagonal of the pattern, they have been carefully chosen in advance to add up to the number being subtracted from N on those lines. Try it! Along the top row 1 + 12 + 7 = 20. Down the right side 11 + 5 + 4 = 20.

Do it again?

Of course you shouldn’t do it twice with the same people as they might spot the pattern of all the common numbers…unless, now you know the secret, perhaps you can work out your own versions each with a slightly different root number, calculated first and so a different template written lightly on different pieces of paper.

Peter McOwan and Paul Curzon, Queen Mary University of London

More on …

- Magic of Computer Science

- Conjuring with Computation: Instant Magic Squares (bonus chapter)

- Magic Booklets