Welcome to the second ‘window’ of the CS4FN Christmas Computing Advent Calendar. The picture on the ‘box’ was a pair of mittens, so today’s focus is on pairs, and a little bit on gloves. Sadly no pear trees though.

1. i-pickpocket

In this article, by a pair (ho ho) of computer scientists (Jane Waite and Paul Curzon), you can find out how paired devices can be used to steal money from people, picking pockets at a distance.

2. Gestural gloves

Working with scientists musician Imogen Heap developed Mi.Mu gloves, a wearable musical instrument in glove form which lets the wearer map hand movements (gestures) to a particular musical effect (pairing a gesture to an action). The gloves contain sensors which can measure the speed and position of the hands and can send this information wirelessly to a controlling computer which can then trigger the sound effect that the musician previously mapped to that hand movement.

You can watch Imogen talk about and demo the gloves here and in the video below, which also looks at the ways in which the gloves might help disabled people to make music.

Further reading

The glove that controls your cords… (a CS4FN article by Jane Waite)

3. Pair programming

‘Pair programming’ involves having two people working together on one computer to write and edit code. One person is the ‘Driver’ who writes the code and explains what it’s going to do, the other person is the ‘Navigator’ who observes and makes suggestions and corrections. This is a way to bring two different perspectives on the same code, which is being edited, reviewed and debugged in real-time. Importantly, the two people in the mini-team switch roles regularly. Pair programming is widely used in industry and increasingly being used in the classroom – it can really help people who are learning about computers and how to program to talk through what they’re doing with someone else (you may have done this yourself in class). However, some people prefer to work by themselves and pair programming takes up two people’s time instead of one, but it can also produce better code with fewer bugs. It does need good communication between the two people working on the task though (and good communication is a very important skill in computer science!).

Here’s a short video from Code.org which shows how it’s done.

4. Digital Twins

A digital twin is a computer-based model that represents a real, physical thing (such as a jet engine or car component) and which behaves as closely as possible to the real thing. Taking information from the real-world version and applying it to the digital twin lets engineers and designers test things virtually, to see how the physical object would behave under different circumstances and to help spot (and fix) problems.

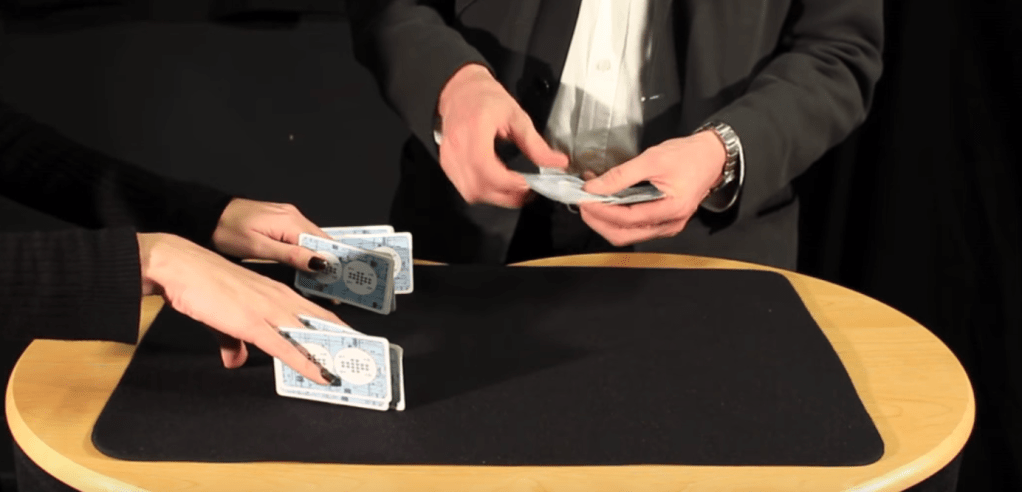

5. A magic trick: two cards make a pair

You will need

- some playing cards

- your hands (no mittens)

- another pair of mitten-free hands to do the trick on

Find a pack of cards and take out 15 (doesn’t matter which ones, pick a card, any card, but 15 of them). Ask someone to put their hands on a table but with their fingers spread as if they’re playing a piano. You are going to do a magic trick that involves slotting pairs of cards between their fingers (10 fingers gives 8 spaces). As you do this you’ll ask them to say with you “two cards make a pair”. Take the first pair and slot them between the first space on their left hand (between their little finger and their ring finger) and both of you say “two cards make a pair”.

Repeat with another pair of cards between ring finger and middle finger (“two cards make a pair”) and twice again between middle and index, and between index and thumb – saying “two cards make a pair” each time you do. You’ve now got 8 cards in 4 pairs in their left hand.

Repeat the same process on their right hand saying “two cards make a pair” each time (but you only have 7 cards left so can only make 3 pairs). There’s one card left over which can go between their index finger and thumb.

Then you’ll take back each pair of cards and lay them on the table, separating them into two different piles – each time saying “two cards make a pair”. Again you’ll have one left over. Ask the person to choose which pile it goes on. You, the magician, are going to magically move the card from the pile they’ve chosen to the other pile, but you’re going to do it invisibly by hiding the card in your palm (‘palming’). To find out how to do the trick, and how this can be used to think about the ways in which “self-working” magic tricks are like algorithms have a look at the full instructions and video below.

6. Something to print and colour in

Did you work out yesterday’s colour-in puzzle from Elaine Huen? Here’s the answer.

Christmas colour-in puzzle

Today’s puzzle is in keeping with the post’s twins and pairs theme. It’s a symmetrical pixel puzzle so we’ve given you one half and you can use mirror symmetry to fill in the remaining side. This is an example of data compression – you only need half of the numbers to be able to complete all of it. Some squares have a number that tells you the colour to colour in that square. Look up the colours in the key. Other squares have no number. Work out what colour they are by symmetry.

So, for example the colour look up key tells you that 1 is Red and 2 is Orange, so if a row said 11111222 that means colour each of the five ‘1’ pixels in red and each of the three ‘2’ pixels orange. There are another 8 blank pixels to fill in at the end of the row and these need to mirror the first part of the row (22211111), so you’d need to colour the first three in orange and the remaining five in red. Click here to download the puzzle as a printable PDF. Solution tomorrow…

The creation of this post was funded by UKRI, through grant EP/K040251/2 held by Professor Ursula Martin, and forms part of a broader project on the development and impact of computing.

EPSRC supports this blog through research grant EP/W033615/1.