How can a machine generate music? It needs an algorithm to follow: instructions to tell it what to do, step by step. Here are two simple games to play that compose a random tune by algorithm.

Writing Notes

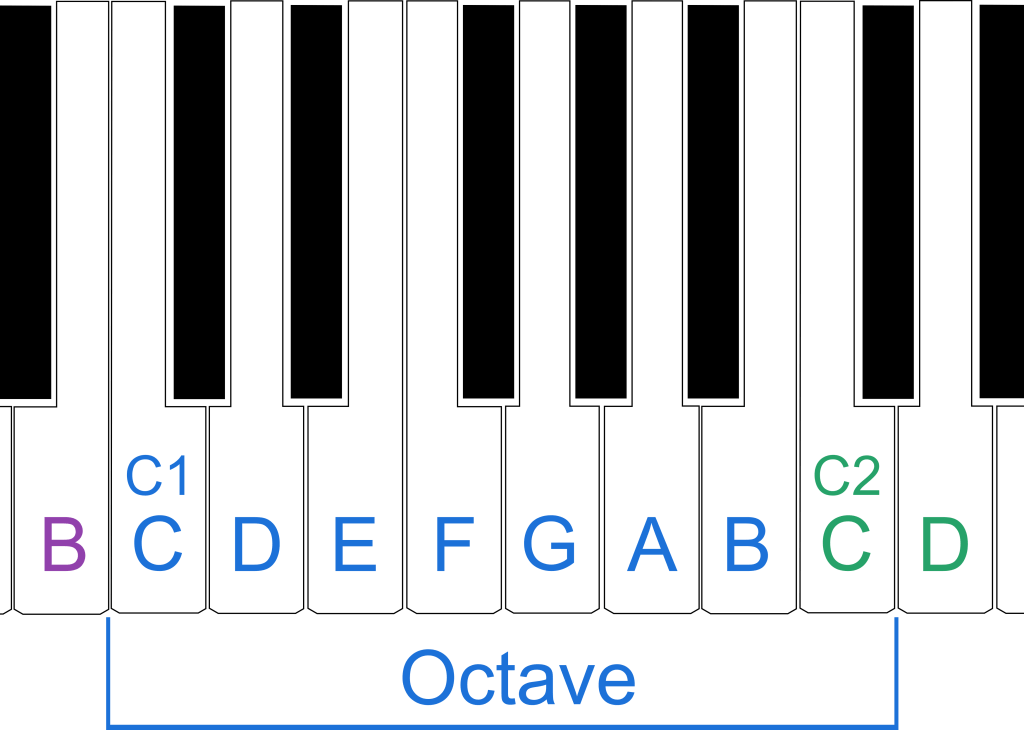

We need a way to write notes. We use letters A to G as on a piano. They repeat all the way up the white keys, so after G comes different higher versions of A, B, C again. We will use notes running from what is called Middle C in the middle of the piano to the next C up. This is called an octave. We will call the two Cs, C1 and C2.

Game 1: Random Jumps

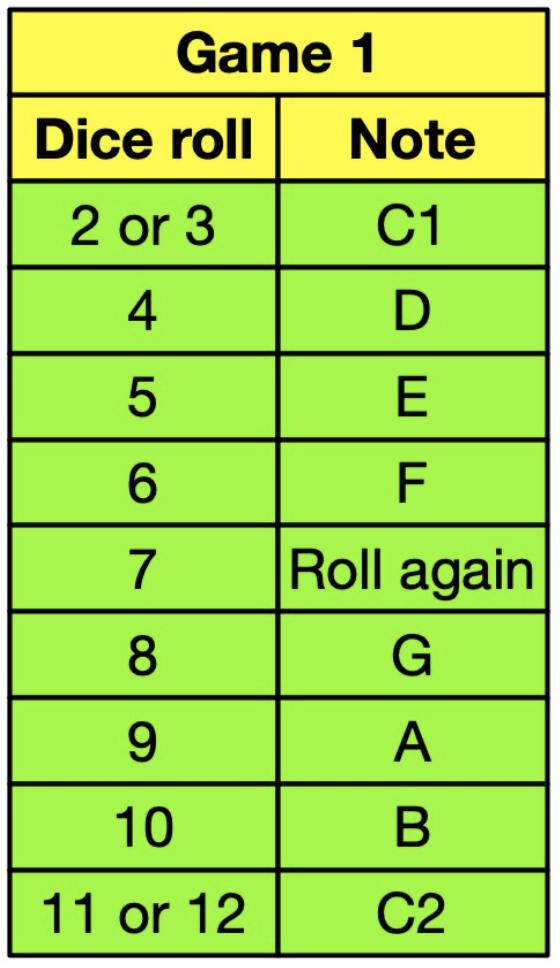

Roll two dice and add the numbers. Write down the note given in the table for Game 1, so if they add to 2 or 3 write down C1, if 4 write down D…If 7 then you get to roll again, and so on. Keep going until you have written 15 notes to make a tune of 15 notes.

Game 2: Up and Down

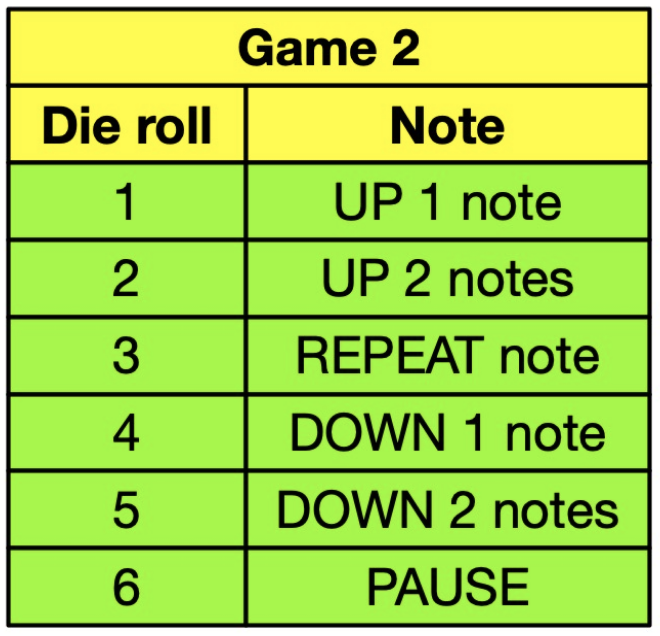

The second algorithm uses one die. First write down C1 then roll the die and do what it says in the Game 2 table. Each new note is based on the last note. If you roll a 1 then write down D (the next note UP from C1). Rolling a 6 means add a pause in the tune (write a dash). If the roll takes you beyond either C then you bounce back: so rolling a 4 when you last wrote C1 means you write C1 again. Rolling 5 from C1 bounces you up to E. Continue until you have 15 notes.

Play your tunes

Play your tunes on any instrument or use a free online piano (see https://bit.ly/pianoCS4FN).

Are they any good? Does either game give better tunes?

Good music isn’t just random notes. That is why we pay composers to come up with the really good stuff! Both human and machine composers learn more complicated patterns of what makes good music.

What do you think of our musical masterpiece?

On Game 1 we rolled 6 4 8 8 8 | 5 9 4 9 6 | 5 6 9 9 10 so our tune is F D G G G | E A D A F | E F A A B

Make your tunes special!

See how on the Bach Google Doodle page.

Here’s what our tune sounds like once harmonies have been added.

Could you improve your tunes by tweaking the notes? Some people use simple algorithms to spark human creativity like that. Rock legend David Bowie helped write a program he then used to write songs. It took random sentences from different places, split them in half and swapped the parts over to give him ideas for interesting lyrics. It was possibly the first algorithm to help write hit songs.

A ‘note’ on bias

Think about the numbers that are rolled and the number of different ways that each number can be produced. For example with two dice (let’s call them ‘left’ and ‘right’) you can make the number 9 twice by rolling a 5 with the left and 4 with the right, or 4 with the left and 5 with the right. Same with 6 and 3. There are only two ways to roll a 2 (both dice have to show 1) or a 3 (a 1 and a 2 or a 2 and a 1). This is baked in to the process and so will affect the notes that appear most often.

Jo Brodie and Paul Curzon, Queen Mary University of London

More on…

We have LOTS of articles about music, audio and computer science. Have a look in these themed portals for more:

- Music and AI

- Music, Digital or Not

- Audio Engineering

- Read more about Music and AI in our mini-magazine “A Bit of CS4FN” issue 6

Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish a new post to the CS4FN blog.