This post is part of the CS4FN Christmas Computing Advent Calendar and we are publishing a small post every day, about computer science, until Christmas Day. This is the fourth post and the picture on today’s door was an ice skate, so today’s theme is Very Cold.

1. IceCube

The South Pole is home to the IceCube Neutrino Observatory. It’s made of thousands of light (optical) sensors which are stretch down deep into the ice, to almost 3,000 metres (3 kilometres) below the surface – this protects the sensors from background radiation so that they can focus on detecting neutrinos, which are teeny tiny particles.

Neutrinos can be created by nuclear reactions (lots are produced by our Sun) and radioactive decay. They can whizz through matter harmlessly without notice (as the name suggests, they are pretty neutral), but if a neutrino happens to interact with a water molecule in the ice then they can produce a charged particle which can produce enough radiation of its own for its signal to be picked up by the sensors. The IceCube observatory has even detected neutrinos that may have arrived from outside of our solar system.

These light signals are converted to digital form and the data stored safely on a computer hard drive, then later collected by ship (!) and are taken away for further analysis. (Although there is satellite internet connection on Antarctica the broadband speeds are about 20 times slower than we’d have in our own homes!).

2. Computer science can help skaters leap to new heights

Researchers at the University of Delaware use motion capture to map a figure skater’s movements to a virtual version in a computer (remember the digital twins mentioned on Day Two of the advent calendar). When a skater is struggling with a particular jump the scientists can use mathematical models to run that jump as a computer simulation and see how fast the skater should be spinning, or the best position for their arms. They can then share that information with the skater to help them make the leap successfully (and land safely again afterwards!).

3. Frozen defrosted

by Peter McOwan, Queen Mary University of London

The hit musical movie Frozen is a mix of hit show tunes, 3D graphics effects, a moral message and loads of topics from computer science. The lead character Princess Elsa creates artificial life in the form of snowman, Olaf, the comedy sidekick, uses nanotechnology based ice dress making, employs 3D printing to build an ice palace by simply stamping her foot and singing and must be complimented for the outstanding mathematical feat of including the word ‘fractal’ in a hit song. In the USA the success of the movie has been used to get girls interested in coding by creating new ice skating routines for the film’s princesses, and devising their own frozen fractals…and let it go, let it go, … you all know the rest.

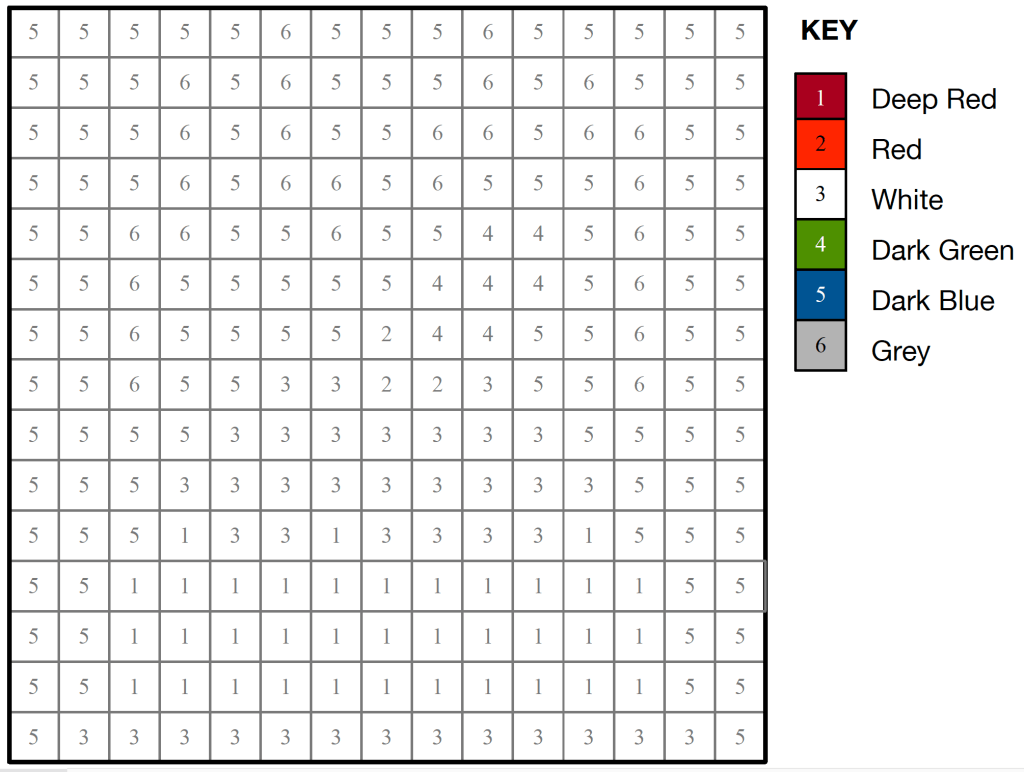

4. Today’s puzzle

This is a kriss-kross puzzle and you solve it by fitting the words into the grid. Answer tomorrow. You need to pay attention to the letter length as that tells you which word can fit where. There is only one four-letter, six-letter and eight-letter word so these can fit only in the grid where there are four, six or eight spaces, so put them in first. There are two three-letter words and two three-letter spaces – the words could be fitted into either space, but only one of them is correct (where the letters of other words will match up). Strategy! Logical thinking! (Also Maths [counting] and English [spelling]).

EPSRC supports this blog through research grant EP/W033615/1.