A group of enthusiasts at Bletchley Park, the top secret wartime codebreaking base, rebuilt a primitive computing device used in the Second World War to help the Allies listen in on U-boat conversations. It was called ‘the Bombe’. Professor Nigel Smart, now at KU Leuven and an expert on cryptography, tells us more.

So What’s all this fuss about building “A Bombe”? What’s a Bombe?

The Bombe didn’t help win the war destructively like its explosive name-sakes but using intelligence. It was designed to find the passwords or ‘keys’ into the secret codes of ‘Enigma’: the famous encryption machine used both by the German army in the field and to communicate to U-Boats in the Atlantic. It effectively allowed the English to listen in to the German’s secret communications.

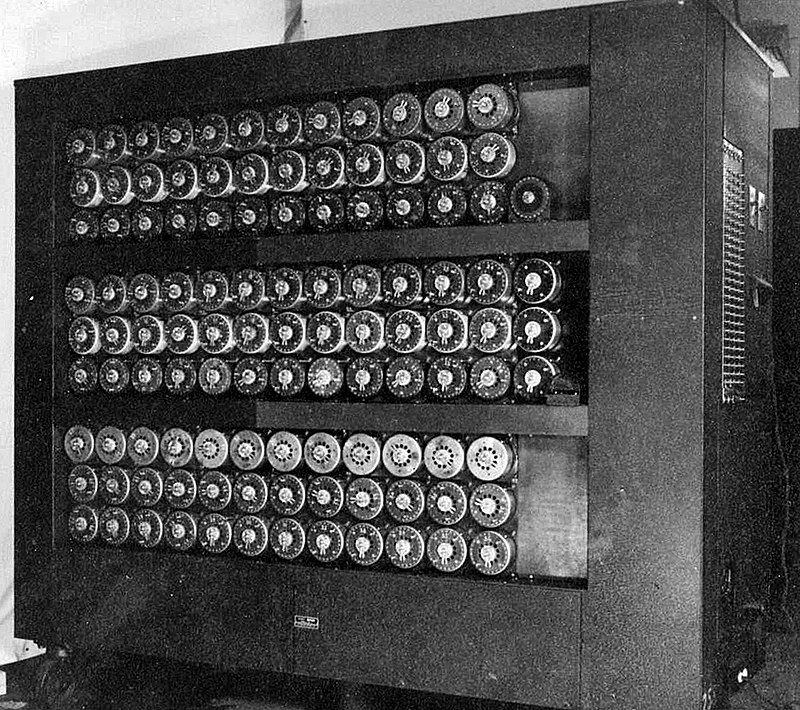

A Bombe is an electro-mechanical special purpose computing device. ‘Electro-mechanical’ because it works using both mechanics and electricity. It works by passing electricity through a circuit. The precise circuit that is used is modified mechanically on each step of the machine by drums that rotate. It used a set of rotating drums to mirror the way the Enigma machine used a set of discs which rotated when each letter was encrypted. The Bombe is a ‘special purpose’ computing device rather than a ‘general purpose’ computer because it can’t be used to solve any other problem than the one it was designed for.

Why Bombe?

There are many explanations of why it’s called a ‘Bombe’. The most popular is that it is named after an earlier, but unrelated, machine built by the Polish to help break Enigma called the Bomba. The Bomba was also an electro-mechanical machine and was called that because as it ran it made a ticking sound, rather like a clock-based fuse on an exploding bomb.

What problem did it solve?

The Enigma machine used a different main key, or password, every day. It was then altered slightly for each message by a small indicator sent at the beginning of each message. The goal of the codebreakers at Bletchley Park each day was to find the German key for that day. Once this was found it was easy to then decrypt all the day’s messages. The Bombe’s task was to find this day key. It was introduced when the procedures used by the Germans to operate the Enigma changed. This had meant that the existing techniques used by the Allies to break the Enigma codes could no longer be used. They could no longer crack the German codes fast enough by humans alone.

So how did it help?

The basic idea was that many messages sent would consist of some short piece of predictable text such as “The weather today will be….” Then using this guess for the message that was being encrypted the cryptographers would take each encrypted message in turn and decide whether it was likely that it could have been an encryption of the guessed message. The fact that the German army was trained to say and write “Heil Hitler” at any opportunity was a great help too!

The words “Heil, Hitler” help the German’s lose the war

If they found one that was a possible match they would analyze the message in more detail to produce a “menu”. A menu was just what computer scientists today call a ‘graph’. It is a set of nodes and edges, where the nodes are letters of the alphabet and the edges link the letters together a bit like the way a London tube map links stations (the nodes) by tube lines (the edges). If the graph had suitable mathematical properties that they checked for, then the codebreakers knew that the Bombe might be able to find the day key from the graph.

The menu, or graph, was then sent over to one of the Bombe’s. They were operated by a team of women – the World’s first team of computer operators. The operator programmed the Bombe by using wires to connect letters together on the Bombe according to the edges of the menu. The Bombe was then set running. Every so often it would stop and the operator would write down the possible day key which it had just found. Finally another group checked this possible day key to see if the Bombe had produced the correct one. Sometimes it had, sometimes not.

So was the Bombe a computer?

By a computer today we usually mean something which can do many things. The reason the computer is so powerful is that we can purchase one piece of equipment and then use this to run many applications and solve many problems. It would be a big problem if we needed to buy one machine to write letters, one machine to run a spreadsheet, one machine to play “Grand Theft Auto” and one machine to play “Solitaire”. So, in this sense the Bombe was not a computer. It could only solve one problem: cracking the Enigma keys.

Whilst the operator programmed the Bombe using the menu, they were not changing the basic operation of the machine. The programming of the Bombe is more like the data entry we do on modern computers.

Alan Turing who helped design the Bombe along with Gordon Welchman, is often called the father of the computer, but that’s not for his work on the Bombe. It’s for two other reasons. Firstly before the war he had the idea of a theoretical machine which could be programmed to solve any problem, just like our modern computers. Then, after the war he used the experience of working at Bletchley to help build some of the worlds first computers in the UK.

But wasn’t the first computer built at Bletchley?

Yes, Bletchley park did build the first computer as we would call it. This was a machine called Colossus. Colossus was used to break a different German encryption machine called the Lorenz cipher. The Colossus was a true computer as it could be used to not only break the Lorenz cipher, but it could also be used to solve a host of other problems. It also worked using digital data, namely the set of ones and zeros which modern computers now operate on.

– Nigel Smart, KU Leuven

More on …

Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish a new post to the CS4FN blog.

This blog is funded by EPSRC on research agreement EP/W033615/1.