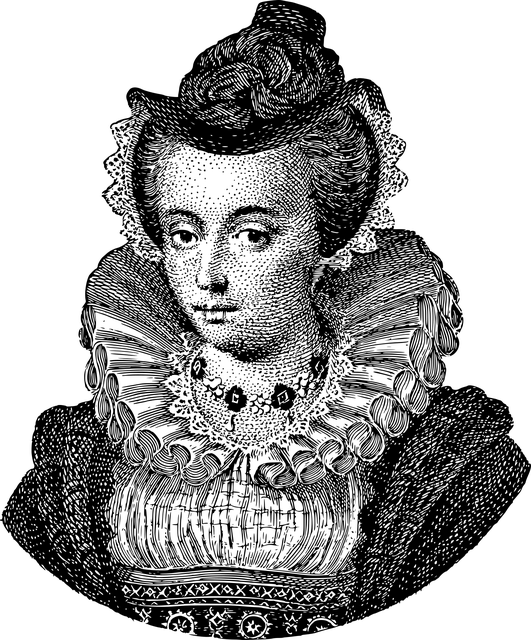

Many of the earliest programmers were women, just as before them many of the human computers were women. It was only later that somehow programming changed in people’s heads to be something men did. One of the earliest was Mexican born, Canadian, Beatrice Worsley. She wrote the first program to be run on the EDSAC computer and gained one of the earliest pure Computer Science PhDs on programming.

Beatrice was outstanding at both Maths and Science at school and at university demonstrated it by coming top in the class in many of the subjects she took during her degree, gaining grades corresponding to a First every year. She spent the war as a Wren in the Canadian Navy (including working as a researcher for the Navy) before going back to university to do a Masters at MIT. There she completed her project that involved surveying virtually all the computing devices of the time (whether completed or planned). Her survey not only included the very primitive computers being bulit immediately after the war, but also the earlier mechanical calculators, such as the ones IBM made its name creating, and differential analysers. The latter are analogue computing devices that were both precursors, and work in a completely different way, to today’s digital machines. Rather than converting data into 0s and 1s they manipulate physical equivalents of actual values as represented by wheels and discs. Unlike the digital computers to come which could be applied to any problem, they solved just one kind of mathematical problem so were not flexible in the way modern computers are.

This Masters thesis set her up for her future career as a computer scientist: she had realised by then that computing was the future. Initially, she got a job helping run IBM mechanical calculators in Toronto. As part of this job she actually built her own working differential anlalyser out of the children’s construction set Meccano.

At this point, Maurice Wilkes ar Cambridge University was building a new kind of machine called EDSAC. This differed from the very first digital computers in that it included stored programs – the program it followed was just data within computer memory, not something physically hard-wired into the machine. This followed the ideas first spelled out by Alan Turing in his description of a Turing Machine and developed by John von Neumann as the von Neumann architecture. It had the basic design we now think of as the basis of modern computers.

Beatrice was sent to Cambridge to find out more about it while it was being constructed, and got involved in getting it to work. It successfully ran its first stored program on 6 May 1949. That first program calculated a table of squares of numbers and it was written by Beatrice, making her the first programmer of what is arguably the first fully-fledged computer as we now know it (as opposed to a demonstration prototype). She also as a result wrote one of the earliest research papers about programs, describing this and other early programs and how they worked on EDSAC. She stayed on in Cambridge to do a PhD on the topic ultimately becoming one of the first people to gain a Computer Science PhD, and probably it was the first PhD about digital computers as we now know them. It built on the work of Computing giants, Alan Turing and Claude Shannon in discussing how programs could efficiently run not just on idealised machines such as Turing Machines, but on real ones like EDSAC. She also wrote more scientific programs for EDSAC, including one to correct pendulum measurements at sea, presumably in part due to her time as a WREN researcher Back in Canada. She also helped design an early programming language, Transcode, and co-wrote a sophisticated compiler for it based on their deep understanding of the hardware. This was because the computer at Toronto, the “Ferranti computer at the University of Toronto” was incredibly tricky to program in its machine code. Worsley could do it but many others struggled. Transcode in effect simulated an easy to program computer running on top of it, based on in idea by John Backus. As a result hundreds of people learnt to program it. Linked to this and starting with her PhD thesis she pioneered the use of programming libraries to make programming easier through her career.

Beatrice Worsley was not the very first person to write a program, or to get a Computing-linked PhD, but she was certainly one of the first, as well as one of the first people to work professionally as a computer scientist. She was certainly a computing pioneer whose programs made history and whose programming research made a solid contribution to the nascent discipline of programming. Computer Science certainly wasn’t a man’s world at the start, and there is no reason why it should be now.

Paul Curzon, Queen Mary University of London

More on …

- A gendered timeline of technology

- The women are (still) here

- Beatrice Helen Worsley: Canada’s Female Computer Pioneer (PDF). [EXTERNAL]

- By Scott Campbell (2003).In IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 25 (4): 51–62 doi:10.1109/MAHC.2003.1253890

- Beatrice Worsley on Wikipedia [EXTERNAL]

Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish a new post to the CS4FN blog.