Mission Impossible always involved the team taking on apparently impossible missions, delivered by a message concluding with the famous line that “This message will self-destruct in 10 seconds”. It was always followed by the message physically destructing in some dramatic way such as flames or smoke coming from the tape recorder. Now, it’s been shown that it is possible to actually do apparently impossible destruction of messages: to send holographic messages that the sender can just make disappear even after they have been sent. It relies on the apparently impossible, but real properties of quantum physics.

A hologram is a 3-dimensional image formed using laser light. It records light scattered from objects coming from lots of different directions. This differs from photography where the light recorded comes from one direction only. You can see examples on the back of bank cards (often a flying dove) where they are used as a hard-to-copy security device.

Now researchers at the University of Exeter have shown it is possible to make quantum holograms that make use of quantum effects. They are made from entangled photons: pairs of light particles that have been linked together in a way that means that, after the entangling, what ever happens to one immediately affects the other too … however far apart they are. Entanglement is one of those weird properties of quantum physics, the physical properties of the very, very small. It means that subatomic particles, once entangled, can later instantly affect each other even when separated by large distances.

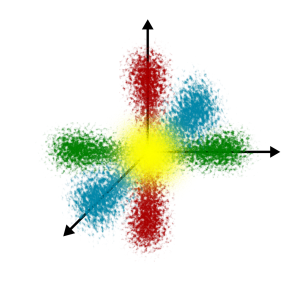

This effect has now been put to novel use by Jensen Li and team in their research at Exeter. They entangled streams of pairs of photons emitted from a crystal using lasers but then separated the pairs. One stream of photons from the pairs was used to create a holographic image on a special kind of material called a meta-material. Meta-materials are just materials engineered at very tiny scales so as to have properties not usually seen in nature. For example, they might be designed to carefully control light or radio waves by reflecting them very precisely in certain directions. One use of that might be so that the object bounces light round from behind it so appears invisible. Some butterfly wings and bird feathers (think peacocks and kingfishers) actually do a similar sort of thing with very precise microscopic scale surface structures that cause their startlingly bright, shimmering colours.

Exeter’s meta-material was flat but with a special surface designed to have tiny features that manipulate light in very precise ways that create a hologram based on the information encoded in the beam of laser light. In their first test that showed their quantum hologram system works, the hologram just showed the letters H,D,V, A. The light from this hologram continued on to a camera, so a picture of the hologram could be taken. So far so normal.

The cunning (and rather weird) thing though is due to what they did to the other stream of light. Each photon in this stream was entangled with a photon in the hologram light stream. Due to the quantum physics of entanglement, that meant that changes to these particles could affect those making the hologram. In particular, the Exeter team had this second stream pass through a polarising filter, essentially like the lens of polaroid sunglasses. Light vibrates in different directions. A sunglasses lens cuts out the light vibrating in a given direction. Now, the letter H in the message was created from light polarised horizontally unlike the other letters which were polarised vertically. This meant that when the second stream of light was passed through a polarising filter blocking out the horizontally polarised light, it also affected the photons entangled with the blocked photons. The other stream of light, that created the hologram, was affected even though it went nowhere near the polarising filter. The result was that the horizontally polarised H could be made to disappear from the message caught on camera. It really did self-destruct, just in a quantum way.

If scaled up such a system could be used to send messages that are still (instantly) controlled by the sender even after they have been sent, whether disappearing or being changed to say something else. The approach could also be incorporated into secure quantum computing communication systems, where the messages are also encrypted.

Fortunately, this blog is not a quantum blog, so will not self-destruct in 10 seconds … so please do share it with your friends!

Paul Curzon, Queen Mary University of London

More on …

Magazines …

Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish a new post to the CS4FN blog.

This blog is funded by EPSRC on research agreement EP/W033615/1.