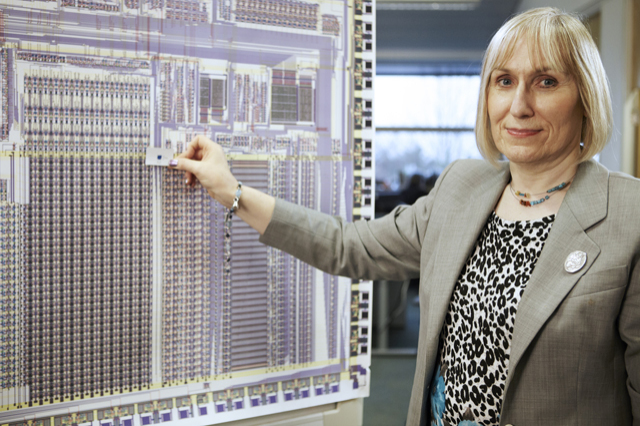

Photo from wikimedia by Charles Rogers CC BY-SA 2.5

MIT professor and transgender activist, Lynn Conway along with Carver Mead, completely changed the way we think about, do and teach VLSI (Very Large Scale Integration) chip design. Their revolutionary book on VLSI design quickly became the standard book used to teach the subject round the world. It wasn’t just a book though, it was a whole new way of doing electronics. Their ideas formed the foundation of the way electronics industry subsequently worked and still does today. Calling her impact as totally transformational is not at an exaggeration. Prior to this, she had worked for IBM, part of a team making major advances in microprocessor design. She was however, sacked by IBM for being transgender when she decided to transition. Times and views have fortunately also been transformed too and IBM subsequently apologised for their blatant discrimination!

A core part of the electronics revolution Mead and Conway triggered was to start thinking of electronics design as more like software. They advocated using special software design packages and languages that allowed hardware designers to put together a circuit design essentially by programming it. Once a design was completed, tools in the package could simulate the behaviour of the circuit allowing it to be thoroughly tested before the circuit was physically built. The result was designs were less likely to fail and creating them was much quicker. Even better, once tested, the design could then be compiled directly to silicon: the programmed version could be used to automatically create the precise layout and wiring of components below the transistor level to be laid on to the chip for fabrication.

This software approach allowed levels of abstraction to be used much more easily in electronics design: bigger components being created from smaller ones, in turn built from smaller ones still. Once designed the detailed implementation of those smaller components could be ignored in the design of larger components. A key part of this was Conway’s idea of scalable design rules to follow as the designs grew. Designers could focus on higher level design, building on previous design and with the details of creating the physical chips automated from the high level designs.

This transformation is similar (though probably even more transformational) to the switch from programming in low level languages to writing programs in high level languages and allowing a compiler to create the actual low-level code that is run. Just as that allowed vastly larger programs to be written, the use of electronic deign automation software and languages allowed massively larger circuits to be created.

Conway’s ideas also led to MOSIS: an Internet-based service whereby different designs by different customers could be combined onto one wafer for production. This meant that the fabrication costs of prototyping were no longer prohibitively expensive. Suddenly, creating designs was cheap and easy, a boon for both university and industrial research as well as for VLSI education. Conway for example pioneered the idea of allowing her students to create their own VLSI designs as part of her university course, with their designs all being fabricated together and and the resulting chips quickly returned. Large numbers could now learn VLSI design in a practical way gaining hands-on experience while still at university. This improvement in education together with the ease with which small companies could suddenly prototype new ideas made possible the subsequent boom in hi-tech start-up companies at the end of the 20th century.

Before Mead and Conway chip design was done slowly by hand by a small elite and needed big industry support. Afterwards it could be done quickly and easily by just about anyone, anywhere.

Paul Curzon, Queen Mary University of London

More on …

Related Magazines …

Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish a new post to the CS4FN blog.

This blog is funded by EPSRC on research agreement EP/W033615/1.

EPSRC also supported this post through research grant EP/K040251/2 held by Professor Ursula Martin.