There are many myths and stories about how different animals gained their distinctive patterns. In 1901, Rudyard Kipling wrote a “Just So Story” about how the leopard got its spots, for example. The myths are older than that though, such as a story told by the San people of Namibia (and others) of how the zebra got its stripes – during a fight with a baboon as a result of staggering through the baboon’s fire. These are just stories. It was a legendary computer scientist and mathematician, who was also interested in biology and chemistry, who worked out the actual way it happens.

Alan Turing is one of the most important figures in Computer Science having made monumental contributions to the subject, including what is now called the Turing Machine (giving a model of what a computer might be before they existed) and the Turing Test (kick-starting the field of Artificial Intelligence). Towards the end of his life, in the 1950s, he also made a major contribution to Biology. He came up with a mechanism that he believed could explain the stripy and spotty patterns of animals. He has largely been proved right. As a result those patterns are now called Turing Patterns. It is now the inspiration for a whole area of mathematical biology.

How animals come to have different patterns has long been a mystery. All sorts of animals from fish to butterflies have them though. How do different zebra cells “know” they ultimately need to develop into either black ones or white ones, in a consistent way so that stripes (not spots or no pattern at all) result, whereas leopard cells “know” they must grow into a creature with spots. They both start from similar groups of uniform cells without stripes or spots. How do some that end up in one place “know” to turn black and others ending up in another place “know” to turn white in such a consistent way?

There must be some physical process going on that makes it happen so that as cells multiply, the right ones grow or release pigments in the right places to give the right pattern for that animal. If there was no such process, animals would either have uniform colours or totally random patterns.

Mathematicians have always been interested in patterns. It is what maths is actually all about. And Alan Turing was a mathematician. However, he was a mathematician interested in computation, and he realised the stripy, spotty problem could be thought of as a computational kind of problem. Now we use computers to simulate all sorts or real phenomena, from the weather to how the universe formed, and in doing so we are thinking in the same kind of way. In doing this, we are turning a real, physical process into a virtual, computational one underpinned by maths. If the simulation gets it right then this gives evidence that our understanding of the process is accurate. This way of thinking has given us a whole new way to do science, as well as of thinking more generally (so a new kind of philosophy) and it starts with Alan Turing.

Back to stripes and spots. Turing realised it might all be explained by Chemistry and the processes that resulted from it. Thinking computationally he saw that you would get different patterns from the way chemicals react as they spread out (diffuse). He then worked out the mathematical equations that described those processes and suggested how computers could be used to explore the ideas.

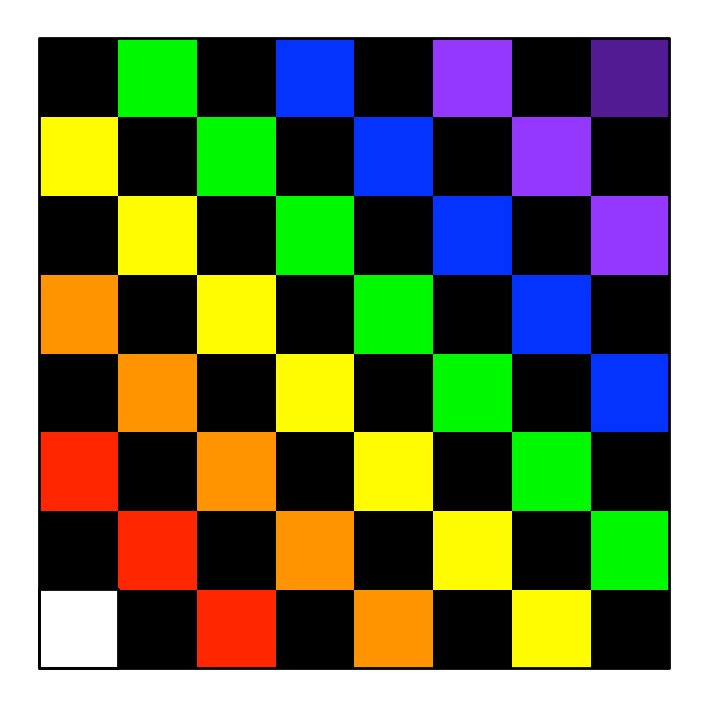

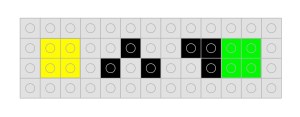

Diffusion is just a way by which chemicals spread out. Imagine dropping some black ink onto some blotting paper. It starts as a drop in the middle, but gradually the black spreads out in an increasing circle until there is not enough to spread further. The expanding circle stops. Now, suppose that instead of just ink we have a chemical (let’s call it BLACK, after its colour), that as it spreads it also creates more of itself. Now, BLACK will gradually uniformly spread out everywhere. So far, so expected. You would not expect spots or stripes to appear!

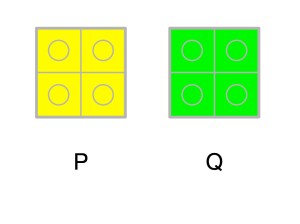

Next, however, let’s consider what Turing thought about. What happens if that chemical BLACK produces another chemical WHITE as well as more BLACK? Now, starting with a drop of BLACK, as it spreads out, it creates both more BLACK to spread further, but also WHITE chemicals as well. Gradually they both spread. If the chemicals don’t interact then you would end up with BLACK and WHITE mixed everywhere in a uniform way leading to a uniform greyness. Again no spots or stripes. Having patterns appear still seems to be a mystery.

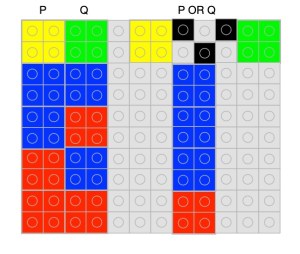

However, suppose instead that the presence of the WHITE chemical actually stops BLACK creating more of itself in that region. Anywhere WHITE becomes concentrated gets to stays WHITE. If WHITE spreads (ie diffuses) faster than BLACK then it spreads to places first that become WHITE with BLACK suppressed there. However, no new BLACK leads to no more new WHITE to spread further. Where there is already BLACK, however, it continue to create more BLACK leading to areas that become solid BLACK. Over time they spread around and beyond the white areas that stopped spreading and also create new WHITE that again spreads faster. The result is a pattern. What kind of pattern depends on the speed of the chemical reactions and how quickly each chemical diffuses, but where those are the same because it is the same chemicals the same kind of pattern will result: zebras will end up with stripes and leopards with spots.

This is now called a Turing pattern and the process is called a reaction-diffusion system. It gives a way that patterns can emerge from uniformity. It doesn’t just apply to chemicals spreading but to cells multiplying and creating different proteins. Detailed studies have shown it is the mechanism in play in a variety of animals that leads to their patterns. It also, as Alan Turing suggested, provides a basis to explain the way the different shapes of animals develop despite starting from identical cells. This is called morphogenesis. Reaction-diffusion systems have also been suggested as the mechanism behind how other things occur in the natural world, such as how fingerprints develop. Despite being ignored for decades, Turing’s theory now provides a foundation for the idea of mathematical biology. It has spawned a whole new discipline within biology, showing how maths and computation can support our understanding of the natural world. Not something that the writers of all those myths and stories ever managed.

– Paul Curzon, Queen Mary University of London

More on …

Magazines …

Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish a new post to the CS4FN blog.

This blog is funded by EPSRC on research agreement EP/W033615/1.