One way to use logical thinking is to deduce new facts but then turn them into IF-THEN rules. They tell us an action to do IF something is true. For example: IF both cards are the same THEN shout SNAP! Once we have IF-THEN rules we can use them as the basis of a program. We can see how this works, and how it involves various computational thinking skills with a simple logical thinking puzzle.

An Egyptian Survey puzzle

Old records show that this area of the desert contains the tombs of 3 scribes (a large tomb covering 3 squares), 1 artisan (medium, 2 squares) and 1 merchant (small, 1 square).

A survey has gathered information of where the tombs could be. Each number tells you how many squares are part of a tomb in that row or column.

Tombs are not adjacent (horizontally, vertically or diagonally).

Can you work out where all the tombs are without further digging?

Solving Egyptian Survey puzzles

The instructions of the puzzle give us some simple facts such as that the number at the end of the row tells us the number of squares in that row holding tombs. On its own that does not tell us how to solve the puzzle. However, thinking logically about it we can draw simple logical conclusions so deduce new facts. For example, it is fairly simple to deduce the fact:

the number for a row being 0 IMPLIES there are no tombs in that row.

If we know there are no tombs in a row then we can mark each square of the row as empty. If we use X to mean nothing is in that square, then we can turn that deduced fact into an action. It means that we can do the following when trying to solve the puzzle:

IF the number on a row is 0 THEN put an X in all the squares of that row.

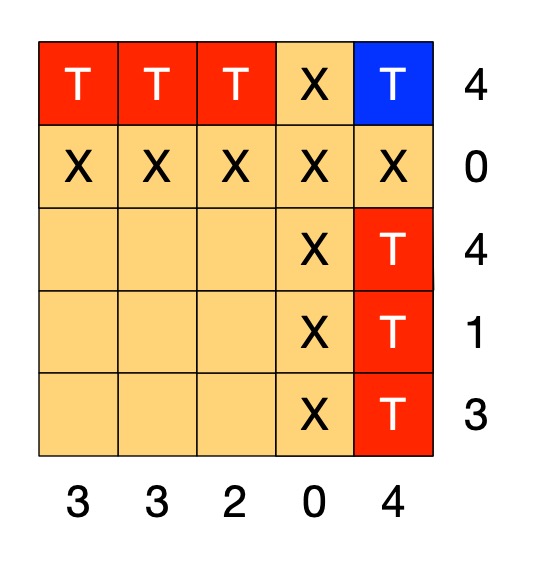

With that rule we can start to solve the puzzle just by following the rule. Find a row numbered 0 and put Xs there. We can create a similar rule for columns. Applying both these rules to our puzzle we get:

Can you work out more rules before reading on?

Rules, rules, rules

What happens if the number of a row is more than 0? Knowing the number alone doesn’t help us much. We need to combine it with other information. The top row of the puzzle has the number 4, for example, but one of the squares already has a cross in it. That means the remaining 4 squares all must have tombs, which we will mark T. We can turn that into a rule:

IF the number for a row is 4 AND there are 4 empty squares in that row and an X

THEN put a T in all the empty squares of that row.

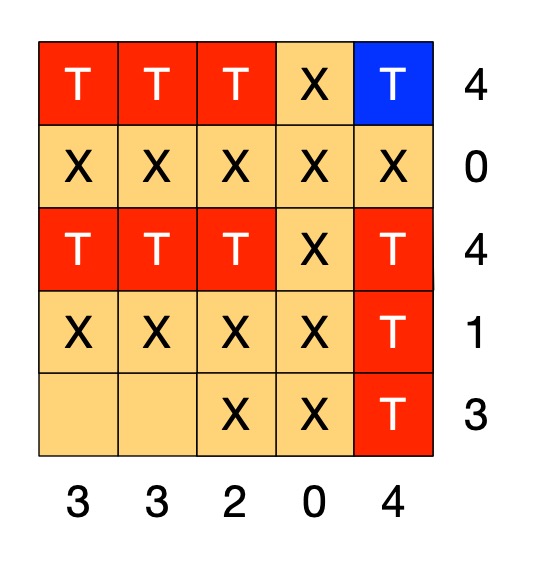

We can make similar rules for each number 1 to 4. We can then create similar rules for columns. Applying them once each to our puzzle gives us:

We could also make a more general version of this rule

IF the number for a row is <n> AND there are only <n> empty squares in that row

THEN put a T in all the empty squares of that row.

This is what computer scientists call generalisation: a part of computational thinking. Instead of having lots of rules (or lines of code) for lots of similar situations, we create one simple but general one that covers all the cases. We can of course apply rules more than once, so as you probably noticed we can apply our row rule once more. In effect our rules live inside a loop and we keep trying them in sequence for as long as we find a rule that makes a difference.

Now one of the rows has the number 1, but we have already marked a tomb in a square of that row. That gives us another rule.

IF the number for a row is 1 AND there is already 1 tomb marked in that row

THEN put an X in all the empty squares of that row.

This gives us:

Similar rules apply for other numbers so we could also make a general version of this rule too.

IF the number for a row is <n> AND there are already <n> tombs marked in that row

THEN put an X in all the empty squares of that row.

Now, applying a column version of the last general rule and we can mark an X in the last square for column with 2 tomb squares.

We need one last rule for this puzzle:

IF the number for a row is <n> AND the number of spaces + the number of 0s is <n>

THEN put a T in all the empty squares of that row.

This is actually an even more general version of our second rule (it is the case where the number of Ts is 0, so could replace that rule with this new one.

Applying it finally solves the puzzle:

If we put our rules together then they become the basis of an algorithm (so program) for solving the puzzles and in creating them from deduced facts we are doing algorithmic thinking. IF-THEN instructions along with sequencing and loops are the basis of all programs. Here we create a sequence of the rules to try in order and put them inside a loop so that we keep trying them until none apply or we have solved the puzzle. There is a style of programming where all a program is is a series of IF-THEN rules – with looping happening implicitly.

Algorithms are just rules to follow that guarantee a result (here solving the puzzle). It is only an algorithm if it guarantees to always work. To solve any (solvable) Egyptian Survey puzzle like this we would need yet more rules: we would need more more rules for it to be an algorithm for solving all puzzles. Making sure algorithms cover all possibilities is one of the harder parts of algorithmic thinking – bugs in programs are often there because the programmer didn’t manage to cover every possibility. In our case we could write a program based on our limited rules. We would just need to include an extra rule that quits (admitting defeat and saying that the program cannot solve the puzzle) if no rule applies.

Perhaps you can work out all the rules (so an algorithm) needed to solve any of these puzzles! All you need are the instructions for the game, some logical thinking to deduce new facts, some algorithmic thinking to turn them into rules, and an ability to generalise so you have a small number of rules … computational thinking skills in fact.

– Paul Curzon, Queen Mary University of London

More on …

Magazines …

Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish a new post to the CS4FN blog.

This blog is funded by EPSRC on research agreement EP/W033615/1.