Tim Berners-Lee, Right to Repair, and a maths puzzle.

Welcome to Day 8 of our CS4FN Christmas Computing Advent Calendar. It features a computing-themed post every day in December until Christmas Day. The blog posts in the Advent Calendar are inspired by the picture on the ‘door’ – and today’s post is inspired by a picture of a Christmas present.

Presents are something you give freely to someone, but they’re also something you hide behind wrapping paper. This post is about a gift and also about trying to uncover something that’s been hidden. Read on to find out about Tim Berners-Lee’s gift to the world, and about the Restart Project who are working to stop the manufacturers of electronic devices from hiding how people can fix them. At the bottom of the post you’ll find the answer to yesterday’s puzzle and a new puzzle for today, also all of the previous posts in this series. If you’re enjoying the posts, please share them with your friends 🙂

1. “This is for everyone” – Tim Berner’s Lee

Audiences don’t usually cheer for computer scientists at major sporting events but there’s one computer scientist who was given a special welcome at the London Olympics Opening Ceremony in 2012.

Tim Berners-Lee invented the World Wide Web in 1989 by coming up with the way for web pages to be connected through links (everything that’s blue and clickable on this page is a link). That led to the creation of web browsers which let us read web pages and find our way around them by clicking on those links. If you’ve ever wondered what “www” means at the start of a link it’s just short for World Wide Web. Try saying “www” and then “World Wide Web” – which takes longer to say?

Tim Berners-Lee didn’t make lots of money from his invention. Instead he made the World Wide Web freely available for everyone to use so that they could access the information on the web. Unless someone has printed this onto paper, you’re reading this on a web browser on the World Wide Web, so three cheers Tim Berners-Lee.

In 2004 the Queen knighted him (he’s now Sir Tim Berners-Lee) and in 2017 he was given a special award, named after Alan Turing, for “inventing the World Wide Web and the first web browser.”

Below is the tweet he sent out during the Olympics opening ceremony.

Further reading

• The Man Who Invented The Web (24 June 2001) Time

• “I Was Devastated”: Tim Berners-Lee, the Man Who Created the World Wide Web, Has Some Regrets (1 July 2018) Vanity Fair

You might also like finding out about “open-source software” which is “computer software that is released under a license in which the copyright holder grants users the rights to use, study, change, and distribute the software and its source code to anyone and for any purpose.”

2. Do you have the right to repair your electronic devices?

A ‘black box’ is a phrase to describe something that has an input and an output but where ‘the bit in the middle’ is a complete mystery and hidden from view. An awful lot of modern devices are like this. In the past you might have been able to mend something technological (even if it was just changing the battery) but for devices like mobile phones it’s becoming almost impossible.

People need special tools just to open them as well as the skills to know how to open them without breaking some incredibly important tiny bit. Manufacturers aren’t always very keen for customers to fix things. The manufacturers can make more money from us if they have to sell us expensive parts and charge us for people to fix them. Some even put software in their devices that stops people from fixing them!

The cost of fixing devices can be very expensive and in some cases it can actually be cheaper to just buy a new device. Obviously it’s very wasteful too.

The Restart Project is full of volunteers who want to help everyone fix our electronic devices, and also fix our relationship with electronics (discouraging us from throwing away our old phone when a new one is on the market). The project began in London but they now run Repair Parties in several cities in the UK and around the world. At these parties people can bring their broken devices and rather than just ‘getting them fixed’ they can learn how to fix their devices themselves by learning and sharing new skills. This means they save money and save their devices from landfill.

Restart have also campaigned for people to have the Right to Repair their own devices. They want a change in manufacturing laws to make sure that devices are designed so that the people who buy and use them can easily repair them without having to spend too much money.

Further reading

The UK’s right to repair law already needs repairing (10 July 2021) Wired UK

The new law to tackle e-waste and planned obsolescence is here but it’s missing some key parts

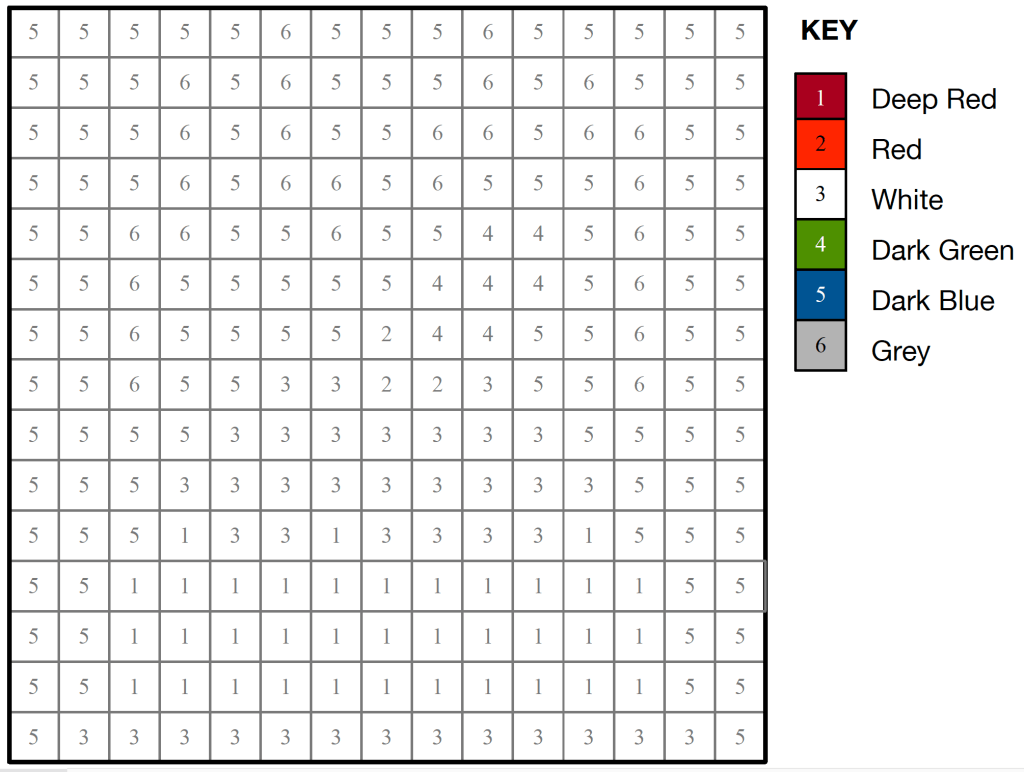

3. Today’s puzzle

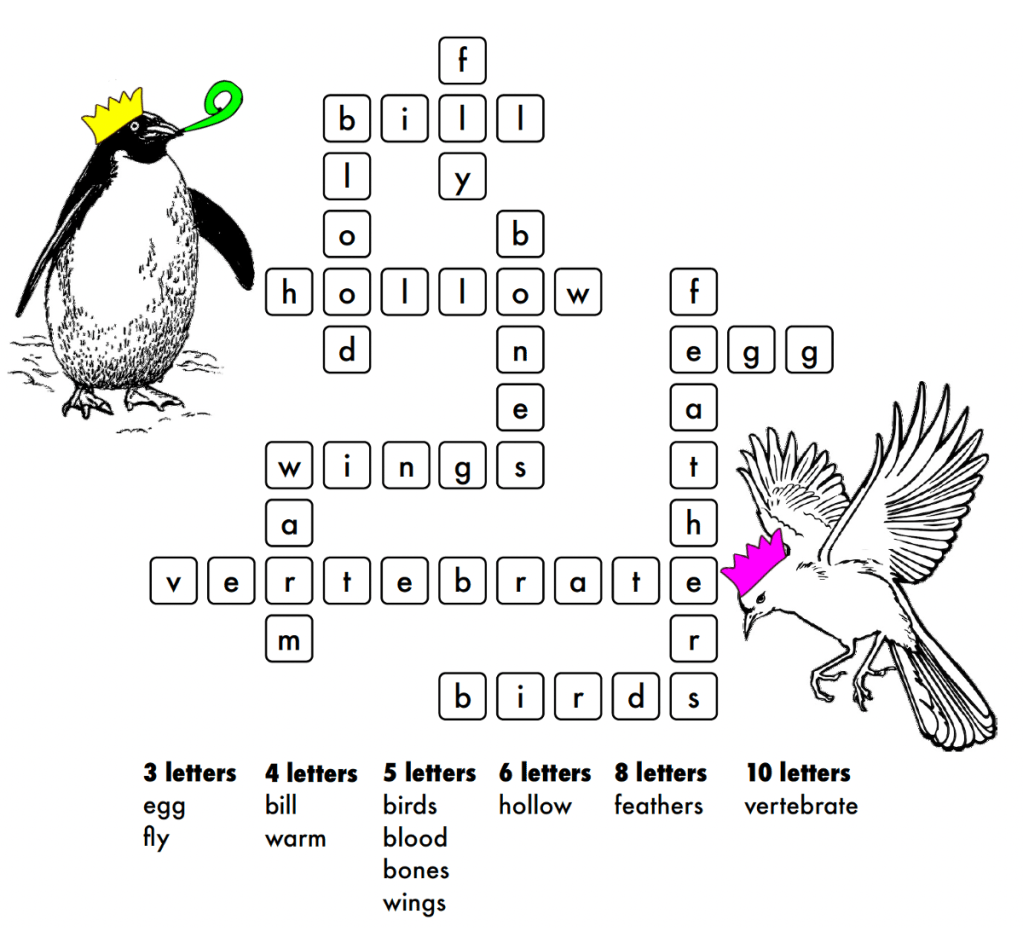

A more mathematical puzzle today. Rather than writing letters into the kriss-kross you need to write the equation and its answer.

For example 5 + 2 = as the clue gives you 5 + 2 = 7 as the answer which takes up 5 characters (note that the answer is not “seven” which also takes up 5 characters!). There are several places in the puzzle where a 5 character answer could go, but which one is the right one? Start with the clues that have only one space they can fit into (the ones with 7 symbols and 9 symbols) then see what can fit around them.

This puzzle was created by Daniel, who was aged 6 when he made this. For an explanation of the links to computer science and how these puzzles can be used in the classroom please see the Maths Kriss-Kross page on our site for teachers. Note that the page does include the answer sheet, but no cheating, we’ll post the answer tomorrow. Also, if you don’t have a printer you can use the editable PDF linked on that page.

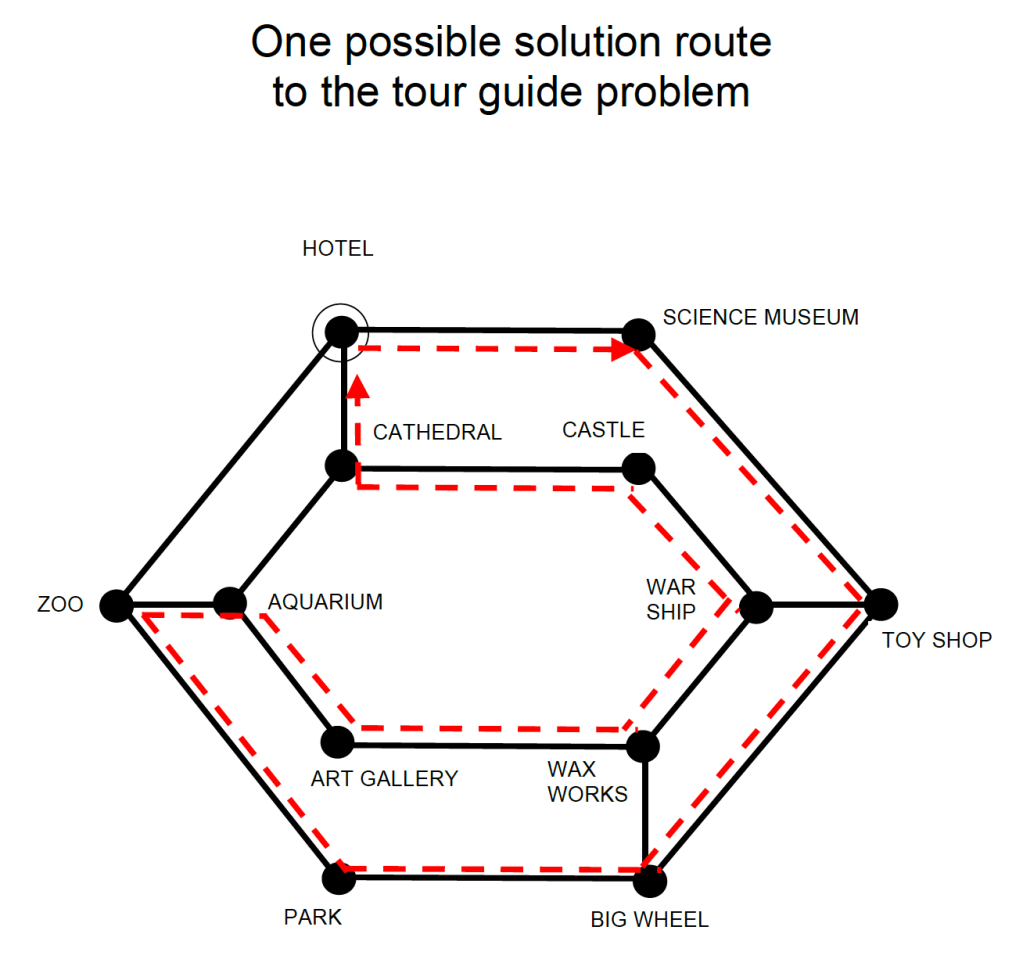

4. Answer to yesterday’s puzzle

The creation of this post was funded by UKRI, through grant EP/K040251/2 held by Professor Ursula Martin, and forms part of a broader project on the development and impact of computing.

EPSRC supports this blog through research grant EP/W033615/1.