Image by WikiImages from Pixabay

Computer scientist Jason Cordes tells us what it was like to work for NASA on the International Space Station during the time of Space Shuttle launches. (From the archive)

Working for a space agency is brilliant. When I was younger, I often looked up at the stars and wondered what was out there. I visited Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas and told myself that I wanted to work there someday. After completing my college degree in computer science, I had the great fortune to be asked to work at NASA’s Johnson Space Center as well as Kennedy Space Center.

Johnson Space Center is the home of the Mission Control Center (MCC). This is where NASA engineers direct in-orbit flights and track the position of the International Space Station (ISS) and the Space Shuttle when it is in orbit. Kennedy Space Center, situated at Cape Canaveral, Florida, is where the Space Shuttle and most other space-bound vehicles are launched. Once they achieve orbit, control is handed over to Johnson Space Center in Houston, which is why when you hear astronauts calling Earth, they talk to “Houston”.

Space City

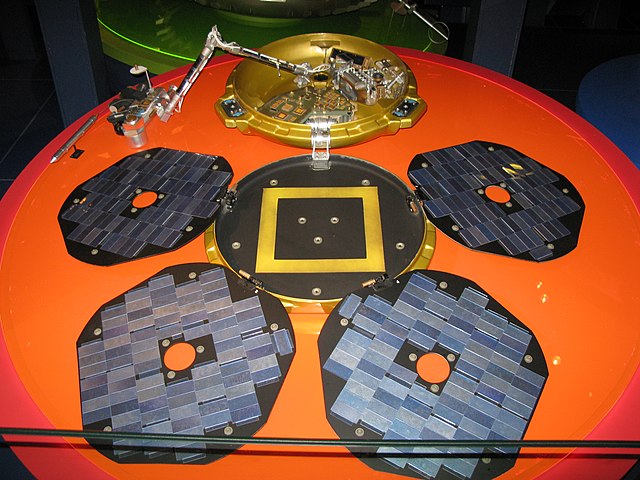

Houston is a very busy city and you get that feeling when you are at Johnson. There are people everywhere and the Space Center looks like a small city unto itself. While I was there I worked on the computer control system for the International Space Station. The part I worked on was a series of laptop-based displays designed to give astronauts on the station a real-time view of the state of everything, from oxygen levels to the location of the robotic arm.

The interesting thing about developing this type of software is realising that the program is basically sending and receiving telemetry (essentially a long list of numbers) to the hardware, where the hardware is the space station itself. Once you think of it like that, the sheer simplicity of what is being done is really surprising. I certainly expected something more complex. All of the telemetry comes in over a wire and the software has to keep track of what telemetry belongs to what component since different components all broadcast over the same wire. Essentially the program routes the data based on what component it comes from and acts as an interpreter that takes the numbers that the space station is feeding and converting them into a graphical format that the astronauts can understand. The coolest part of working in Houston was interacting with astronauts and getting their feedback on how the software should work. It’s like working with celebrities.

Wild times

While at Kennedy Space Center, I was tasked with working on the Shuttle Launch Control System for the next generation of shuttles. The software is very similar to that used to control the ISS. The thing I remember most about working there was the environment.

Kennedy Space Center is about as opposite as you can get from the big city feeling at Johnson. It’s situated on what is essentially swampland on the eastern coast of Florida. The main gates to Johnson are right on major streets within Houston, but at Kennedy the gate is on a major highway, and even then, travel to the actual buildings of the Space Center is a leisurely 30 minute drive through orange groves and trees as well as bypassing causeways and creeks. Along the way you might spot an eagle’s nest in one of the trees, or a manatee poking its head from the waters. Kennedy is in the middle of a wildlife preserve with alligators, manatees, raccoons and every other kind of critter you can imagine. In fact, I was prevented from going home one evening by a gator that decided to warm itself up by my car.

The coolest thing about working at NASA, and specifically Kennedy Space Center, was being able to watch shuttle launches from less than 10 miles away. It’s an incredible experience. The thundering engines vibrate throughout your body like being next to the speakers at an entirely too loud rock concert. Night launches were the most amazing, with the fire from the engines lighting up the sky. It is very amazing to watch this machine and realise that you are the one who wrote the computer program that set it in motion. I’ve worked in a few development firms, but few of them gave me as much emotion when I saw it in action as this did.

More on …

Related Magazines …

Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish a new post to the CS4FN blog.

This blog is funded by EPSRC on research agreement EP/W033615/1.